This is the nineteenth in this year's series of posts by PhD students on the job market.

While sociable peers increase your social skills, higher-achieving peers do not improve your academic performance. That is the main conclusion of my job market paper.

As the world bends closer towards automation, social skills take a lead role on individuals' well-being and labor market success. According to Deming (2017), between 1980 and 2012, jobs demanding high levels of social interaction grew by nearly 12 percentage points as a share of the U.S. labor force. Similarly, a recent column by the Washington Post highlights the importance of social skills for team productivity and employment opportunities. It describes the results of Google’s Project Aristotle, which concludes that the best teams at Google exhibit high levels of soft skills, and particularly social skills. These include emotional safety, equality, generosity, curiosity towards the ideas of your teammates, empathy, and emotional intelligence

While there is extensive research on policies that improve academic learning, little is known about how social skills form. My job market paper addresses this challenge. I present the results of a large-scale field experiment at boarding schools in Peru. The intervention was designed to estimate social and cognitive peer effects. While other studies have exploited random assignment to dormitories and classrooms, I use a novel experimental design to generate large variation in peer skills. Specifically, I assign students to two cross-randomized treatments in the allocation to beds in a dormitory: (1) less or more sociable peers, and (2) lower- or higher-achieving peers. This design surmounts many of the challenges with traditional approaches to the study of peer effects (Manski, 1993; Angrist, 2014; Caeyers and Fafchamps, 2016).

To classify students as less vs. more sociable, I use the position in the friendship network the year before the intervention. A student with a better position has a greater influence in the network and therefore is more sociable. in the schools’ social network. In fact, in the context of my study, this indicator of sociability is highly correlated with other metrics introduced by psychologists to measure social skills. To classify students as higher vs. lower achieving, I use students’ scores from the schools’ admissions tests, which include math and reading comprehension scores.

Main Results

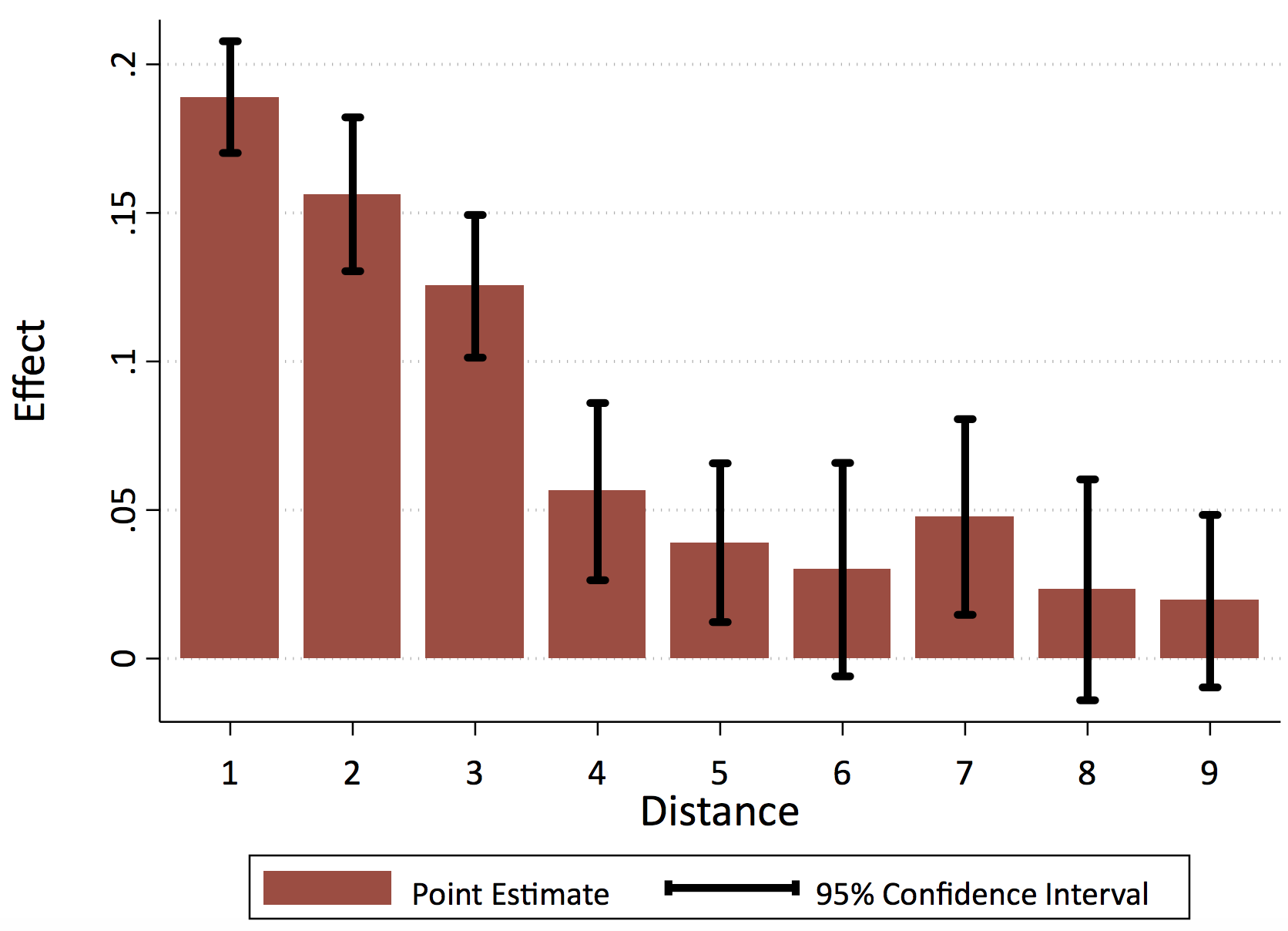

The allocation to beds influenced the social network formation in the schools. Students befriend, study, and play more with peers that were assigned to nearby beds; the closer the peer, the stronger the interaction (Figure 1). Being neighbors in a dormitory matters; it increases the likelihood of social interactions by 18 percentage points. The effect of proximity is no different for students assigned to higher- and lower-achieving peers, and it is slightly higher for students assigned to more sociable peers.

Figure 1: Impact of Distance in the Dormitory on the Likelihood of Social Interactions.

While social links can be relevant on their own, how do these links affect the formation of skills? I estimate the impact of each treatment on the formation of social and cognitive skills. To measure social skills, the primary outcome is a social skills index that includes psychological tests and the number of peers that perceive the student as a leader, or a popular, friendly, or shy person. By using peers’ perceptions to measure a student's social skills, I account for biases in self-reported psychological tests. I also present results for the two “Big Five” personality traits that are related to social skills: (i) extraversion, characterized by positive affect and sociability and (ii) agreeableness, the tendency to act in a cooperative and selfless manner (McCrae and John, 1992; John and Srivastava, 1999; Almlund et al., 2011). In the paper, I include several social skills measures to assess the robustness of the results. I use grades and test scores in math and reading comprehension to measure cognitive outcomes.

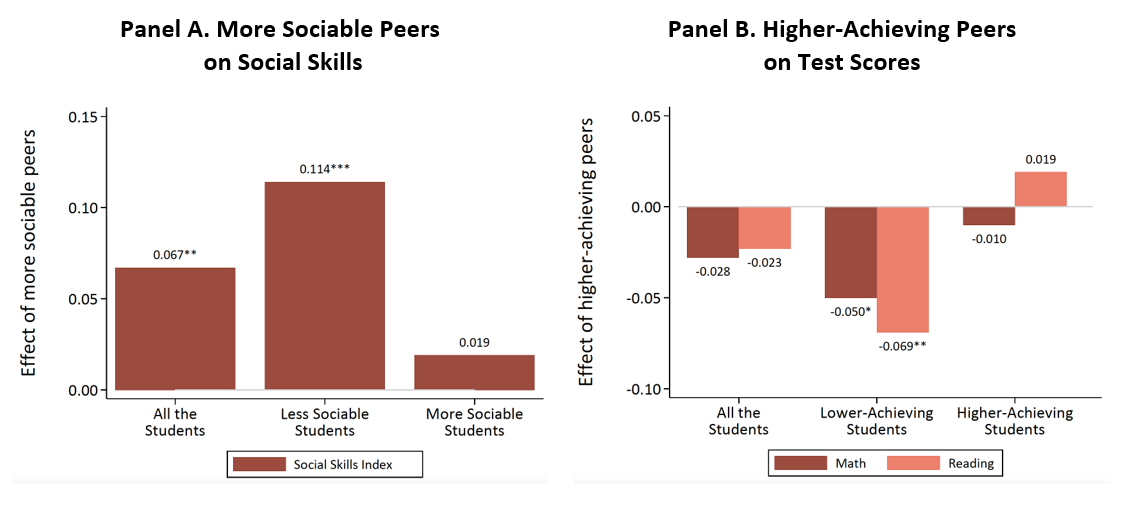

I find that sociable peers have a positive effect on a student’s social skills. Students that were randomly assigned to dormitories with more sociable peers have a higher social skills index—0.067 standard deviations—after the intervention (Panel A, Figure 2). In turn, Deming (2017) estimates that an increase in a one standard deviation of a similar social skills index increases wages in 3.7%. The positive effect on social skills in my study is mainly driven by the impact on students that were less sociable at baseline. These results are consistent with the impacts on the Big Five personality traits, and with the impacts on measures that account for biases in self-reported tests—less sociable students assigned to more sociable peers are perceived as more friendly and popular. I do not find that having more sociable peers affects a student’s academic scores.

By contrast, the results show that higher-achieving peers have no impact on the average student’s social or cognitive skills. Furthermore, my results suggest that higher-achieving peers decrease the academic achievement of lower-achieving students (Panel B, Figure 2). These effects are similar for grades and test scores, and for both math and reading comprehension.

Figure 2: Impact of Treatments on Students’ Outcomes

Mechanism: Self-confidence

I explore potential mechanisms that drive these results and show that changes in students' self-confidence in their skills is a valid mechanism. The idea behind this self-confidence story is that it is easier for less sociable students to engage in social activities with more—rather than less—sociable peers, and these interactions make students more successful. Success translates into more self-confidence in social skills, making students more likely to do well in future interactions with both roommates and other people. By contrast, lower-achieving students feel less accomplished when assigned to higher-achieving peers. If students think they are doing worse, they are less confident in their academic skills, driving down their investment and performance in academic activities. Hence, while more sociable peers make less sociable students feel better about their social skills, higher-achieving peers make lower achieving students feel worse about their cognitive skills

I find empirical evidence suggesting that changes in self-confidence are driving the results in my paper. Less sociable students report better social interactions with their roommates when assigned to more sociable peers. They are also more likely to say they are friendly and popular, and less being shy. By contrast, lower-achieving students show less self-confidence in their cognitive abilities when assigned to higher-achieving peers.

Overall, while the existing literature and most education policies have focused on peers’ academic achievement, this paper shows that in the context of selective boarding schools in Peru, the role of sociable peers is more important to improve students’ outcomes. Further research is needed to assess whether students can learn social skills from their peers in other settings.

Román Andrés Zárate is a Ph.D. Candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Join the Conversation