Recently there has been a resurgence in the arguments to measure poverty at the individual level. Currently, while poverty lines are set at an individual level of consumption, the standard poverty measures take household consumption and divide by the number of people (or “equivalent adults”). But maybe, just maybe, there is intrahousehold inequality.

This pattern, and it’s consequences, are the topic of an elegantly written forthcoming paper by Rossella Calvi (older, ungated version here). She pulls together a range of diverse data sources to how older females in India are relatively disadvantaged in consumption and how this traces through to mortality.

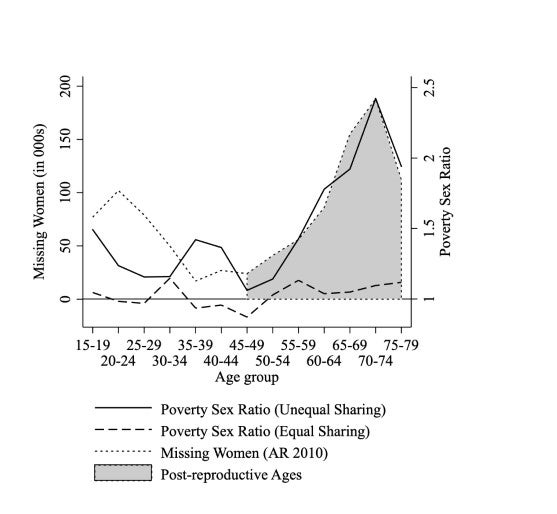

Calvi starts with the motivation of missing women. We’ve heard about this from Amartya Sen and others. And a lot of this could be to early mortality or selective abortion. However, Calvi builds on Anderson and Ray’s argument that, in India, a fair number of the missing women are older.

Critical to Calvi’s documenting this inequality and how it matters for morbidity is the Hindu Succession Act (HSA). This was a law first passed in 1956 to try and equalize girls’ inheritance rights. It only applied to Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains. And it didn’t quite do the trick in giving girls equal inheritance rights. Hence starting in 1976, some states passed amendments to improve things (HSAA – for the amendments). And this provides the variation that Calvi uses to examine a potential change in women’s bargaining position. (A number of other papers have looked at a range of other effects of the HSA and she has an excellent review of this literature).

Before we get to that, let’s look at what she finds in terms of women’s health and exposure to HSAA. Women married (or of marriage age) after HSAA have significantly better health outcomes. They are 4.7 percentage points (or 20 percent) less likely to be underweight, and 1.2 percentage points (80 percent) less likely to be severely anemic. The literature has documented that both of these are associated with increased risk of mortality.

Indeed, when Calvi looks at morbidity and mortality in the data, she finds that exposure to HSAA leads to an 8.8 percentage point reduction in the probability of being ill over the last 2 weeks, and a 0.02 reduction in the probability of dying in the last year (this is not a super common event – so this translates into a 4 percent reduction in the chance of dying).

These are important effects. And Calvi sets to work to show us one potential key mechanism. Her focus is on intrahousehold bargaining power. Calvi starts from the idea of collective household model (so one in which there are bargaining power/weights and allocations are pareto efficient) and provides a really clear and well laid discussion of this kind of model and how they work.

With the model in hand, she turns to a fairly detailed consumption survey (the beauty of Indian data!) that allows her to assign clothing at men, women and children. This will allow her to back out the resource shares that adult women get relative to men (with a couple of assumptions). She has women’s age, state, and religion in these data, so she can look at how exposure to the HSAA impact these resource shares. And she finds that HSAA exposure increases research shares by 0.9 to 2.3 percentage points – which is in line with some of the earlier work showing that the HSA increased women’s self-reported bargaining power.

In addition, the estimation of these resource shares give her a predicted resource share for not only women, but also men and children for each household. Using this, she can look at overall inequality and she finds that in households with children, women’s resource shares are around 67 percent of men’s and in households without children, women come in at 80 percent of the male share. Keeping in mind the puzzle of missing older women, Calvi digs in further and looks at women’s relative shares of resources across ages. During the prime reproductive years, she finds something that looks close to equality, but above 45 this drops off, with a low of women getting about 65 percent of male resources.

Now one potential explanation for this could be that women work less than men as they get older, and this reduces the bargaining power. However, Calvi shows that women not only keep up their share of unpaid care work, but also that the gender gap in hours worked for pay is actually smaller among older women. So this isn’t explaining things. Which leaves two other potential explanations: the norm that child bearing and rearing are women’s primary duty and the potential that older women have worse outside options than men (e.g. older men can marry younger women much more easily than the reverse).

The resource shares also allow Calvi to estimate individual poverty. She finds some interesting patterns. First, in about 25 percent of the sample, there are households where the men do not live in poverty but the women do. Second, in terms of headcount, 22 percent of women live below the extreme poverty line, while only 17 percent of men do. For children (even after adjusting for their lower consumption needs), extreme poverty rates are a staggering 44 percent. Finally, returning to age, she shows that male poverty doesn’t vary much with age, but female poverty is worst in the 15-19 and 70-74 age groups. And the gap in poverty rates between men and women starts to widen at 45 and grows beyond that.

OK, so how does this tie into mortality. Calvi’s consumption dataset doesn’t have mortality. But she artfully takes the poverty data and maps it onto the mortality/missing women data.

Here you can see that as the poverty inequality (solid line) increases above the age of 45 it lines up really well with the pattern of missing women.

So this is pretty convincing that bargaining power seems to have a lot to do with excess mortality of women beyond the prime reproductive years. For sure other things matter for this, but this shows a strong relationship that explains a fair amount. And to show how us how policy could help close this gap, Calvi runs the scenario of what would happen if all women were eligible for the HSAA reforms (i.e. got much closer to equal inheritance rights). First, this drops female poverty by 7.5 percent. Second, it reduces the post-reproductive gender gap in poverty by 27 percent. And finally, doing a back of the envelope (and heavily caveated) calculation, this would have resulted in a 19 percent reduction in mortality of women of post-reproductive ages.

All in all, this is a really creative paper that brings together a range of different datasets as well as some nice exogenous variation and smart modeling work to show us how intrahousehold inequality, and poverty at the individual level, matters. Matters a lot.

Join the Conversation