This is the seventeenth, and penultimate, of this year’s job market series.

Research question and motivation

That early-life events can affect adult outcomes is now well established. Lifelong health, education, and wages are all shaped by events of the in-utero and early-childhood environments (Barker 1992; Cunha and Heckman, 2007; Almond et al., 2017). To the extent that adverse shocks can often not be prevented, a key task for researchers and policymakers is to ascertain the potential for and degree of mitigation: Could investing in children's health and education help reduce gaps caused by early-life adversities?

In my job-market paper, we study whether the returns on human capital investments on children differ by exposure to adverse early-life shocks. We focus on two shocks that significantly affect households in developing countries: adverse weather shocks -- i.e., floods and droughts, which reduce children's initial skills--, and the introduction of conditional cash transfers (CCTs), which provide monetary subsidies to families with young children conditional on investments in children's health and education. In particular, we provide empirical evidence on how the effects of CCTs on children's long-term educational outcomes interact with children's early-life exposure to adverse weather shocks.

Why should we care?

Because both weather shocks and CCT programs are policy relevant!

- Weather shocks are becoming more prevalent with increasingly unpredictable intensity and duration.

- Developing countries are disproportionately more affected by weather shocks than other countries (Dell et al., 2014).

- Children in poor countries may be the group most at risk from weather shocks as they are not only more physically vulnerable than adults, but are less able to dissipate heat or protect themselves under extreme conditions (Hanna and Oliva, 2016).

- Developing countries have limited health infrastructure and safety-net programs.

- CCTs have become a popular mechanism for alleviating poverty. Today, more than 60 low- and middle-income countries (including the U.S. and the U.K.) operate CCTs and their costs represent a large component of the social safety net. Therefore, learning about their potential direct and indirect impacts is imperative.

Why is there so little evidence on the interaction between shocks and investments?

Few empirical studies have estimated these interactions, possibly due to the great challenge it involves. As discussed by Almond and Mazumder (2013), providing causal evidence on interaction effects---i.e., addressing the potential endogeneity between child endowments and parental, school, or government responses---a researcher would need exogenous variation in both shocks and subsequent investments. In my job-market paper, we provide the first evidence on how these interactions vary by developmental stages, by using a unique setting in Colombia in which two exogenous shocks affected similar cohorts of children over their lives.

Research design and data

Using the universe of students in Colombian public schools, we combine a difference-in-difference (DD) framework with a regression discontinuity design (RDD) to exploit two sources of exogenous variation:

- Exposure to adverse weather shocks in early life. We exploit the temporal and geographic variation in exposure to El Niño and La Niña events. During these episodes, the normal patterns of tropical precipitation and atmospheric circulation are disrupted, triggering extreme climate events around the globe such as droughts, floods, and hurricanes. During the 1990s, Colombia experienced three events: El Niño droughts of 1991–1992 and of 1997–1998 and La Niña floods of 1998–2000. Our DD specification compares the outcomes of children born in the same municipality but in different months and years during the 1990s, and therefore exposed to varying levels of extreme rainfall (i.e., floods or droughts) during these episodes.

- The introduction of CCTs. Familias en Acción, Colombia's CCT program, was rolled out in the early 2000s targeting low-income households based on a poverty index score called SISBEN, which allows us to estimate an RDD of the effects of the program on children’s outcomes.

Our outcomes include measures of educational attainment and achievement that broadly capture changes in initial skills that may have been affected by the weather-shock exposure and the CCTs, and any potential reinforcing or compensatory parental investments. In particular, we focus on i) school retention, ii) being “on time” for 7 th, 8 th, or 9 th grade, and iii), the ICFES test score, a mandatory exam that high school graduates take regardless of college attendance.

Figure A illustrates our research design combining a DD with an RDD.

Main results

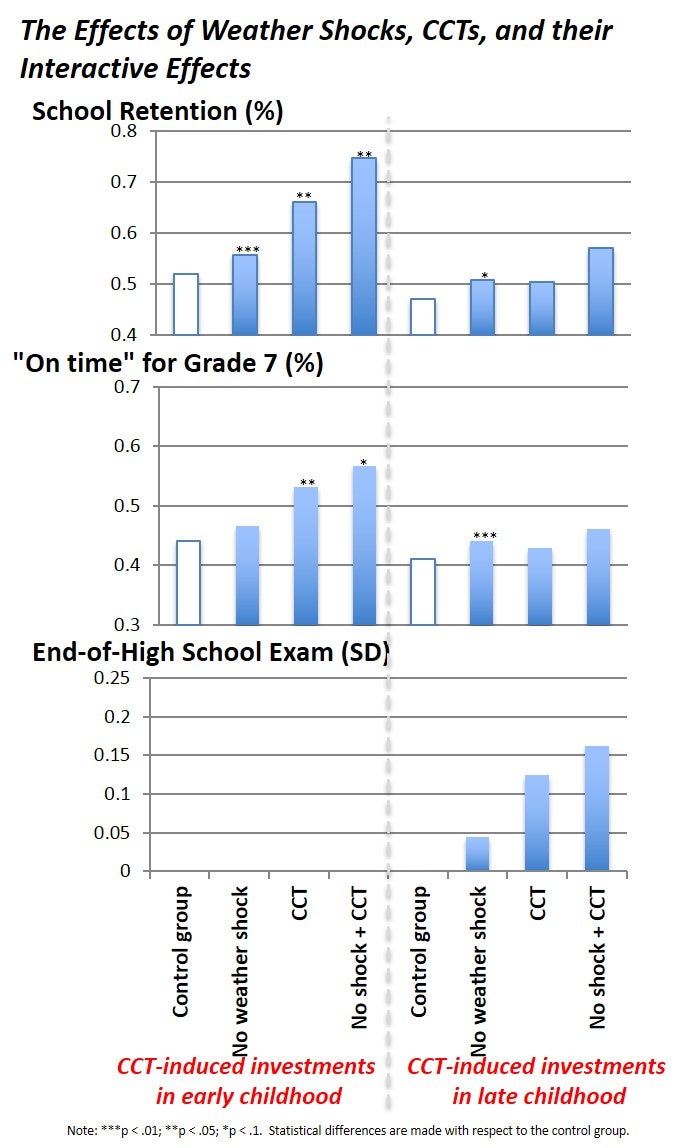

Our estimates obtained from the DD framework with the RDD provide two sets of findings summarized in Figure B.

- Weather shocks: Not being exposed to the adverse weather events of El Niño and La Niña in the first years of life improves children's long-term educational outcomes, increasing school retention by 6.5%; whether a child is “on time” for 7th, 8th, and 9th grade by 5.9%, 6.1%, and 6.6%, respectively; and the ICFES score by 0.05 standard-deviations (SD). Stronger effects were found when the weather exposure occurred from in-utero to age 3.

- CCT-induced investments and their interactive effects with weather shocks: The CCT increases the probability of school retention by 10%; the chance of being “on time” for 7th, 8th, and 9th grade by 11.7%, 12.5%, 11.6%; and the ICFES score by 0.13 SD. Most importantly, we find that both the timing and type of CCT-induced investments (i.e., health vs. education investments resulting from the conditionality) play a crucial role in both the effect of CCTs and their interactive effects with weather shocks. By focusing on outcomes we can measure for both young and old cohorts---mainly school retention and being on “time” for grade (the ICFES is only observed for older cohorts)--we find that when the CCT-induced investments occur in sensitive periods of human capital formation (e.g., early childhood), the returns of the program are large and their interactive effects with weather conditions suggest that the returns of the program are even larger for weather-unaffected children. In contrast, CCT-induced investments that come relatively late in childhood (e.g., adolescence) have a smaller “main'” effect, and a smaller or zero interactive effect with the weather shock.

- We also find that CCT-induced health investments tend to have larger returns than CCT-induced educational investments. Comparing children within the same age range at CCT rollout, who were exposed for a similar period to the program, we find that children who were slightly younger when the CCT arrived and who were therefore eligible to receive the CCT-induced health investments, experience a 9% higher probability of school retention than children who were slightly older at CCT rollout, and therefore eligible to receive the CCT-induced educational-investments.

- The evidence in 1-3 is consistent with theoretical models on human-capital formation predicting that: i) timing and type of investments matter and ii) investments in children at a given period may make subsequent investments more productive, known as dynamic complementarities (Cunha and Heckman, 2007).

Mechanisms

We examine some potential pathways through which El Niño and La Niña affected children’s education. Using the Demography and Health Survey data, we find that no weather shock exposure:

- Has a small and contemporaneous positive effect on household income of 2.2%, but this effect tends to dissipate after two years.

- Increases household food consumption by 2.4%, and in particular the consumption of grains, fruits, and vegetables.

- Improves children’s health in the short, medium, and long term: The probability that a child is low birth weight falls by 15%, and child’s height-for-age and young adults’ height increases by 0.16 SD and 0.10 SD, respectively.

These findings suggest that child’s health and nutritional status might be relevant pathways through which early-life weather shocks affect educational outcomes.

Final remarks

- The findings of this paper shed new light on the developmental production function of human capital and the role of social policies in closing gaps generated by early-life adversities.

- Although we find that CCTs do not fully eliminate gaps caused by adverse weather shocks, our results highlight the importance of intervening early in children's lives to maximize program effectiveness and minimize initial gaps across groups.

Limitations

Our study faces several limitations relevant to interpreting the results:

- We focus on measures of educational attainment and achievement. Educational attainment has the limitation that, more attainment may not necessarily be an optimal decision if the opportunity cost of studying is greater than the labor-market wage. To some extent, focusing on test scores at age 18 helps address this issue, as test scores may partially reflect labor-market productivity; however, one limitation of using test scores is that there is selection into who takes the exam.

- We do not have administrative health records, which would be ideal to examine health as a “final” outcome or as a potential mechanism on the actual sample of interest.

- Because we use an RDD to estimate the effects of Familias en Acción, our treatment effects cannot be generalized to other families located at different points in the poverty distribution.

Join the Conversation