This is the twelfth in our series of posts by students on the job market this year.

Joint work with Karine Marazyan and Paola Villar

“Saving? In Senegal, you don't have the possibility to save! Because the family is here, there is the pressure, there is the electricity bill to pay, the medical prescription of your brother you are asked to pay, and there are your parents to help. It is like that here: as long as you are working, people consider you don't have financial problems.” (Public-primary-school teacher in Guinaw Rail, suburb of Dakar, Senegal, Boltz and Villar 2013)

In developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, individuals frequently transfer a substantial share of their income to members of their social networks: members of the household or extended family, friends, and neighbors. This informal redistribution has been widely studied by the economic literature for its role as a risk-sharing system, in economies with limited access to formal financial markets and to public redistribution (for a review, Cox and Fafchamps, 2007). However, this is only one side of the coin: transfers can fulfill important social needs that do not necessarily match economic ones, and could be driven by altruism, charity, social prestige (Wright, 1994), and strong social obligations for redistribution (Platteau, 2000, 2006, 2014).

Akin to a taxation system, redistributive pressure can induce strong distortions in economic decisions for labor supply, investment and resource allocation, through widespread strategies aimed at circumventing this redistributive pressure (Baland et al., 2011, 2015; di Falco and Bulte, 2011; Grimm et al., 2013). Such adverse effects of informal redistribution can subsequently constitute an important barrier to economic development in these countries. However, causal estimations of the effect of informal redistribution are scarce, given how hard it is to identify redistributive pressure using observational data. Few pioneer papers have relied on lab-in-field or field experiments (Hadness et al., 2013; Castilla and Walker, 2013; Beekmann et al., 2015). The closest paper to ours is from Jakiela and Ozier (2015), who explored how investment decisions in the lab are distorted when observed by the volunteer participants from the same community in rural Kenya.

My job market paper is the first paper to both identify the individual cost of the social pressure to redistribute, through the willingness-to-pay (WTP) to hide income, and to relate it to distortions in real-life resource allocation decisions. Three main research questions are addressed:

- Who is trying to escape these social obligations to redistribute, and how much do they value being able to relax these obligations?

- How do people's resource-allocation choices change when they are offered the opportunity to escape redistributive pressure?

- From whom are people hiding their income: their household members, their kin outside the household, or their neighbors?

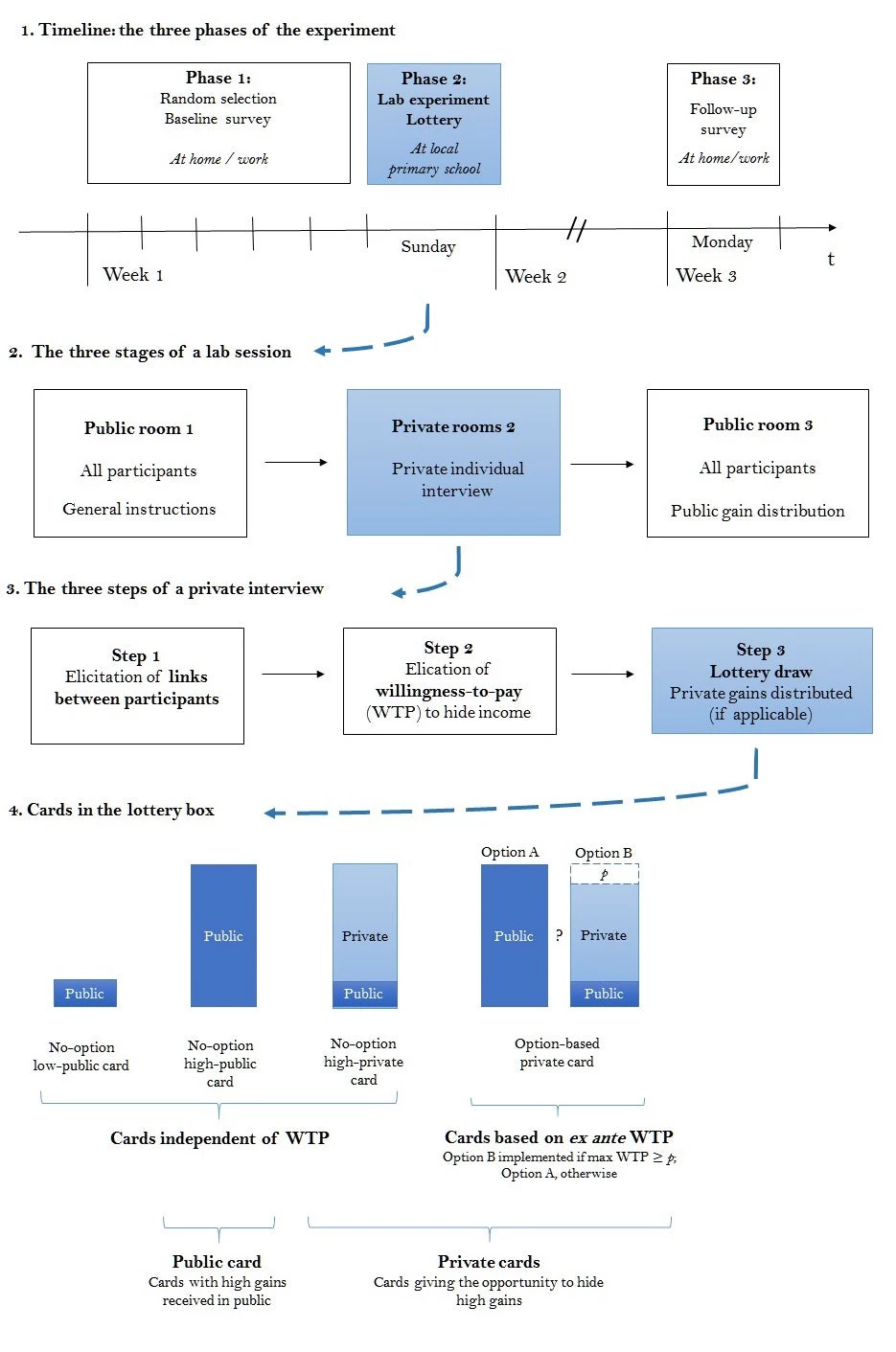

To answer these questions, along with my colleagues, Karine Marazyan and Paola Villar, I conducted a lab-in-the-field experiment in poor, densely populated urban communities in the Dakar region, Senegal, in June 2014. The experiment uniquely combines a lab phase and a small-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT) for a random sample of 797 participants. The figure at the end of the post presents the steps of the experiment.

To tackle the first question, we elicited the WTP to hide income for all participants in the lab phase, through a multiple-choice list method. Choices between public or costly private gains were incentivized by a subsequent lottery (see Figure). This enabled us to estimate the deadweight loss associated with redistributive pressure for the whole sample.

To answer the second question, we estimated the impact of redistributive pressure on real-life decisions, relying on the RCT component. Following the lottery, some participants got the opportunity to hide part of their gains from other participants. We did not impose any structure of transfer or investment decisions in the lab setting and rather left the participants free to choose how to allocate their gains once back home. Then, we resurveyed participants one week later to observe their decisions.

For the third question, we rely on two dimensions: the random selection of the pool of participants, – and thus of observers of the lottery outcomes –, and the distinction in out-of-the-lab outcomes between transfers made within the household, to kin or non-kin in the community. We can thus identify to what extent the results are driven by redistributive pressure from within the household, from kin in the community, or from other neighbors.

We find the following results for each question raised:

- What is the cost of redistributive obligations? We find a high WTP to hide income: 65% of subjects prefer to receive their gains in private rather than in public, and among them, they are ready to forgo on average 14% of their unobserved income. Men are willing to pay more than women are. For both men and women, the poorest are willing to pay a higher price to hide their earnings than the richest women are, relative to their consumption level.

- How does redistributive pressure distort resource allocation choices? Looking at out-of-the-lab allocation choices, individuals who are willing to hide but who randomly receive their gains in public transfer to kin on average 25% of their income. In contrast, the participants who are willing and able to hide their lottery gains transfer 27% less – they reallocate this amount mostly toward private goods and health care (though the latter effect is weaker). Women in poorest households invest a lower share of their income in small inputs when they are able and willing to hide. Consistent with qualitative evidence found in Senegal, this suggests that these women make small investments as a strategy to have more control over their resources and thus, to transfer less.

- From whom do people hide their income? Women are willing to pay a higher price for income privacy if one of their kin from the community participates in the same session. They also transfer less to kin outside the household, but not to household members, when they can hide their gains. In contrast, men transfer less, both to kin within and outside the household, when they are willing and able to hide. We investigate the mechanisms behind the observed reduction in transfers and how it varies across gender and across the kin ties in another paper currently underway.

Marie Boltz is a postdoctoral fellow at University of Namur. She graduated from the Paris School of Economics in 2015. Personal webpage

Join the Conversation