New York Times published an article last week, titled “

The Future of Not Working.” In it, Annie Lowrie discusses the universal basic income experiments in Kenya by GiveDirectly: no surprise there: you can look forward to more pieces in other popular outlets very soon, as soon as they return from the same villages visited by the Times. One paragraph of the article drew my attention in particular: “One estimate, generated by Laurence Chandy and Brina Seidel of the Brookings Institution, recently calculated that the global poverty gap — meaning how much it would take to get everyone above the poverty line — was just $66 billion. That is roughly what Americans spend on lottery tickets every year, and it is about half of what the world spends on foreign aid.”

Well, I don’t know about you, but that paragraph makes me think that if we just were able to divert 50% of the current foreign aid budget towards cash transfers, we would eliminate extreme poverty. But, is that really true? The answer is: “not even close.”

See, that calculation assumes that we know exactly who is poor, how far below the poverty line each person exactly is, give them that precise amount, etc. (Actually, Zhang, Chandy, and Noe outline their simplifying assumptions in footnote 2 of this post.) How close are we to that in reality? Again, far away – at least in developing countries.

There are actually quite a few economists who have been working on targeting issues to reduce poverty for decades: two of them are Dominique van de Walle and Martin Ravallion. In a recent paper that they co-authored with Caitlin Brown (addendum here), they examine the best methods we have available for targeting poor people to see how they would fare in reducing poverty.

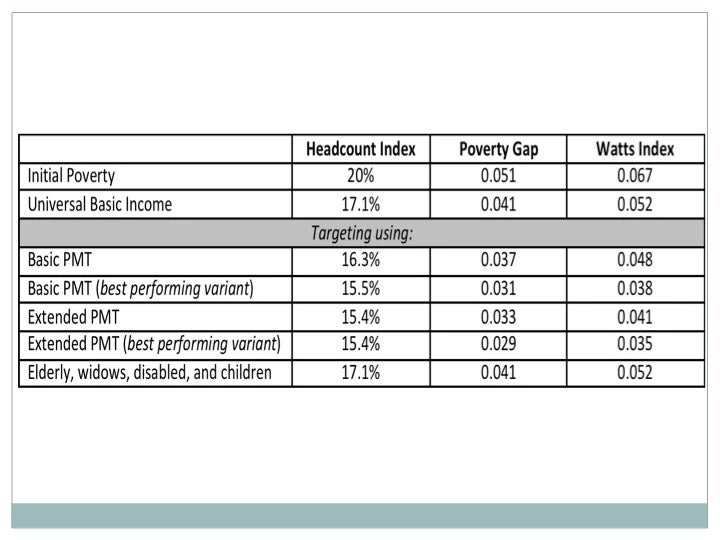

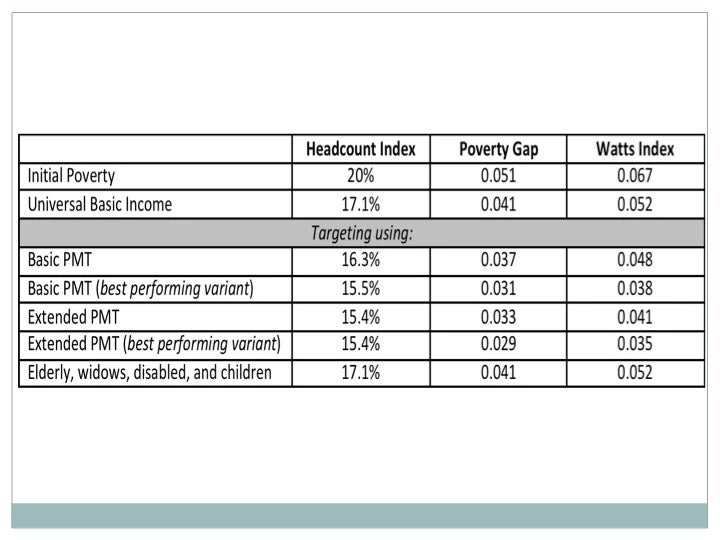

Their mental exercise is simple: suppose that you have enough money to eliminate poverty if you made all those simplifying assumptions you read above. Now, get rid of the assumption that is near impossible to satisfy, i.e. that you can correctly identify every poor person and give them exactly the difference between their income and the poverty line, and replace it with more reasonable ones used by policy makers. These policies include a universal basic income, targeting on the basis of basic proxy-means tests (PMT) most commonly used by governments and donor organizations, improvements to PMT they propose, and some simple categorical targeting options (such as targeting the elderly, children, widows, etc.). They then ask a straightforward question: by how much would each policy reduce poverty? [1]

Turns out, not by much. Or, more precisely, by less than 25% depending on your choice of poverty measure. Take a look at this table that I made borrowing figures from Tables 11-13 in their paper:

Several observations from this table:

However, to come even close to eliminating poverty today (a claim made by Michael Faye of GiveDirectly in the same article), we would need much much more than half of the world’s foreign aid budget. Suppose that we gave 75 cents per day to everyone in the world, which would not eliminate extreme poverty, how much money would we need? If I am counting zeros correctly, about 2 trillion dollars, or about 30 times more than the $66 billion figure cited in the NYT article. Take away a couple of billion people in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand: we’re still not close. And, that scheme would not eliminate poverty, even setting the poverty line at $1.9/day. What if we wanted people to actually live on closer to $8-10 per day…

So, my plea to media outlets covering this topic: consider requesting an interview with a few researchers who spent their entire careers worrying about poverty reduction (like this professor or this one, both of whom won awards for their work on poverty). There are a lot of reasons for us to consider UBI in the portfolio of possible policy choices towards poverty reduction. But, a little restraint and sticking to the existing research and facts would go a long way in creating a healthy debate.

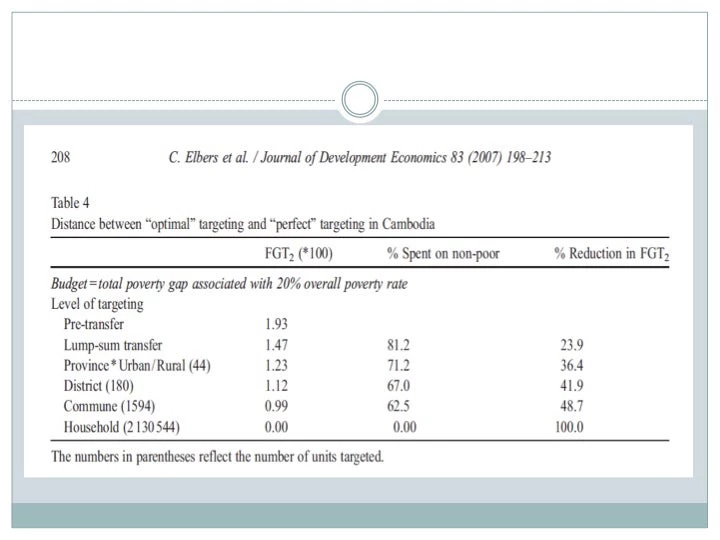

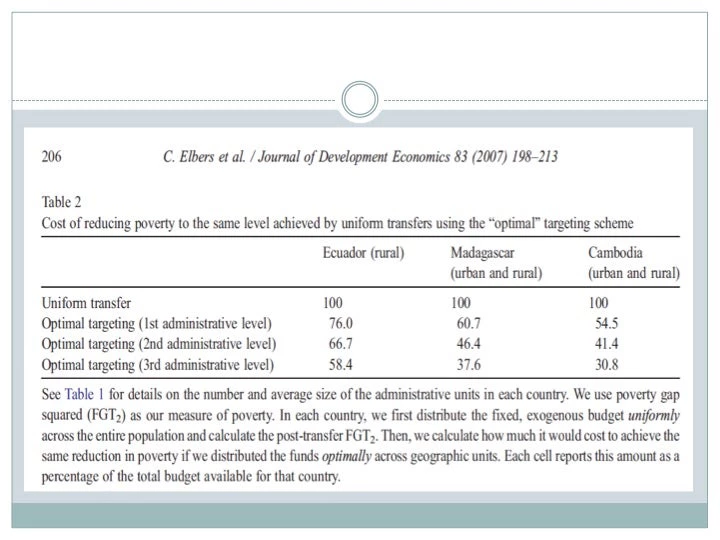

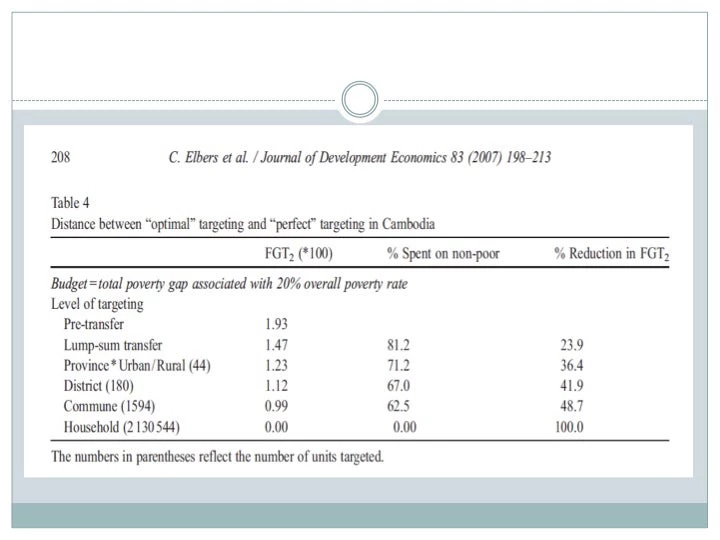

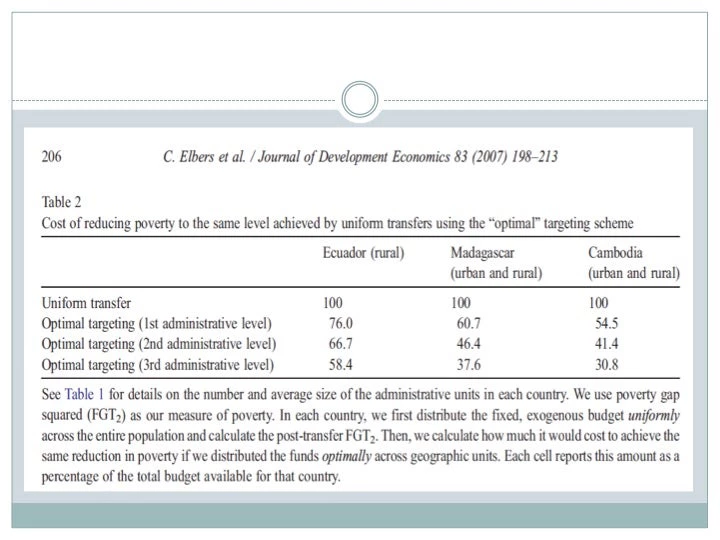

P.S. It so happens that I co-authored a similar paper, which was published in the Journal of Development Economics 10 years ago. Below, please find Tables 2 & 4 borrowed from that paper, which show remarkably similar findings to those in Brown et al. (2016), but using geographic targeting (poverty maps) instead of PMT. Not only the poverty reduction via UBI vs. targeting methods is very similar (24% vs. 49% in the last column of Table 4 immediately below), but note the cost savings achieved by geographic targeting vs. UBI to achieve the same amount of poverty reduction.

Well, I don’t know about you, but that paragraph makes me think that if we just were able to divert 50% of the current foreign aid budget towards cash transfers, we would eliminate extreme poverty. But, is that really true? The answer is: “not even close.”

See, that calculation assumes that we know exactly who is poor, how far below the poverty line each person exactly is, give them that precise amount, etc. (Actually, Zhang, Chandy, and Noe outline their simplifying assumptions in footnote 2 of this post.) How close are we to that in reality? Again, far away – at least in developing countries.

There are actually quite a few economists who have been working on targeting issues to reduce poverty for decades: two of them are Dominique van de Walle and Martin Ravallion. In a recent paper that they co-authored with Caitlin Brown (addendum here), they examine the best methods we have available for targeting poor people to see how they would fare in reducing poverty.

Their mental exercise is simple: suppose that you have enough money to eliminate poverty if you made all those simplifying assumptions you read above. Now, get rid of the assumption that is near impossible to satisfy, i.e. that you can correctly identify every poor person and give them exactly the difference between their income and the poverty line, and replace it with more reasonable ones used by policy makers. These policies include a universal basic income, targeting on the basis of basic proxy-means tests (PMT) most commonly used by governments and donor organizations, improvements to PMT they propose, and some simple categorical targeting options (such as targeting the elderly, children, widows, etc.). They then ask a straightforward question: by how much would each policy reduce poverty? [1]

Turns out, not by much. Or, more precisely, by less than 25% depending on your choice of poverty measure. Take a look at this table that I made borrowing figures from Tables 11-13 in their paper:

Several observations from this table:

- Universal Basic Income (UBI) reduces the Headcount Index by 14.5 percent (it reduces the Watts Index, which is preferred by the authors for its desirable properties, by 22.4 percent, but most people in the world count the poor).

- Categorical targeting (see the last row) performs very similarly to UBI.

- With enough money to eliminate poverty with perfect information and no transactions costs, the best targeting tools we have available to us reduce the Headcount Index only by 23 percent. We do significantly better if we care about distribution-sensitive measures of poverty (43 to 48 percent reduction in the Poverty Gap and Watts Index, respectively) – but only if we improve upon the common PMT methods by using poverty quantile regressions or means from panel data when available.

- The difference between the performance of UBI and the best targeting method looks small. But, that is a little deceiving: note that in a country of 25 million people, such as Cameroon, reducing the Headcount Index from 17.1% to 15.4% allows close to half a million people escape poverty. Given the budget neutrality of this result, you may still choose to target transfers to the poor – if the various costs of targeting (administrative, as well as on social cohesion, etc.) are not too high. Again, if we care about distribution-sensitive measures of poverty, the performance of best PMT targeting is much better than UBI or categorical targeting.

However, to come even close to eliminating poverty today (a claim made by Michael Faye of GiveDirectly in the same article), we would need much much more than half of the world’s foreign aid budget. Suppose that we gave 75 cents per day to everyone in the world, which would not eliminate extreme poverty, how much money would we need? If I am counting zeros correctly, about 2 trillion dollars, or about 30 times more than the $66 billion figure cited in the NYT article. Take away a couple of billion people in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand: we’re still not close. And, that scheme would not eliminate poverty, even setting the poverty line at $1.9/day. What if we wanted people to actually live on closer to $8-10 per day…

So, my plea to media outlets covering this topic: consider requesting an interview with a few researchers who spent their entire careers worrying about poverty reduction (like this professor or this one, both of whom won awards for their work on poverty). There are a lot of reasons for us to consider UBI in the portfolio of possible policy choices towards poverty reduction. But, a little restraint and sticking to the existing research and facts would go a long way in creating a healthy debate.

P.S. It so happens that I co-authored a similar paper, which was published in the Journal of Development Economics 10 years ago. Below, please find Tables 2 & 4 borrowed from that paper, which show remarkably similar findings to those in Brown et al. (2016), but using geographic targeting (poverty maps) instead of PMT. Not only the poverty reduction via UBI vs. targeting methods is very similar (24% vs. 49% in the last column of Table 4 immediately below), but note the cost savings achieved by geographic targeting vs. UBI to achieve the same amount of poverty reduction.

[1] They do this exercise in nine sub-Saharan African countries and assume a poverty headcount of 20% and 40%. They state reductions in poverty headcount, poverty gap, and Watts index. The variants don’t make much of a difference to the main conclusions, so I present their findings for 20% poverty headcount here. A quick trip to

PovcalNet suggests that the share of these nine countries living under $1.9/day is much higher than 20%. Same source suggests about 41% for sub-Saharan Africa as a whole and about 17% for the world (

this article from the World Bank puts the last figure at about 11%). So, the exercise assuming a poverty headcount of 20% is perfectly reasonable.

Join the Conversation