“Just because it worked in Brazil doesn’t mean it will work in Burundi.” That’s true. And hopefully obvious. But some version of this critique continues to be leveled at researchers who carry out impact evaluations around the world. Institutions vary. Levels of education vary. Cultures vary. So no, an effective program to empower girls in Uganda might not be effective in Tanzania.

Of course, policymakers get this. As Markus Goldstein put it, “Policy makers are generally not morons. They are acutely aware of the contexts in which they operate and they generally don’t copy a program verbatim. Instead, they usually take lessons about what worked and how it worked and adapt them to their situation.”

In the latest Stanford Social Innovation Review, Mary Ann Bates and Rachel Glennerster from J-PAL propose a four-step strategy to help policy makers through that process of appropriate adaptation of results from one context to another.

Let’s walk through one example that they provided and then one of my own. In India, an intervention that provided raw lentils each time parents brought their children for immunization and then a set of metal plates for completing all needed vaccinations (at least 5 visits) had a dramatic impact: Completed immunizations jumped from 6 percent in comparison communities to 39 percent in incentive communities. As J-PAL works with several governments to boost immunization rates, they follow the 4 steps:Step 1: What is the disaggregated theory behind the program?

Step 2: Do the local conditions hold for that theory to apply?

Step 3: How strong is the evidence for the required general behavioral change?

Step 4: What is the evidence that the implementation process can be carried out well?

- Theory behind original program: Parent do not oppose vaccination, but they are sensitive to small price changes.

- Local conditions in the new context: How do parents feel about vaccination in Sierra Leone or in Pakistan? Here, they propose a suggestive piece of evidence: If parents take their children for at least one immunization but then fail to get the rest, it suggests they aren’t opposed to vaccination per se but rather may be sensitive to transport or other costs. This seems to be the case in both new settings.

- Evidence on changing behavior: There is lots of evidence that people underinvest in preventive care and that they are sensitive to price gaps.

- Possibility of Implementation: Could Sierra Leone or Pakistan pull off this kind of incentive program? Bates’ and Glennerster’s take: In Pakistan, probably yes because of the deep penetration of mobile money. But in Sierra Leone, it remains to be tested whether incentives could be effectively delivered to parents via the clinics.

- Theory behind the India study: There are students of wildly different ability in a given class, and most students are behind the curriculum. It’s difficult or impossible for teachers to reach all student levels in one class, and students learn more effectively when they receive instruction at their level. (In the case of the India study, the technology facilitates that.)

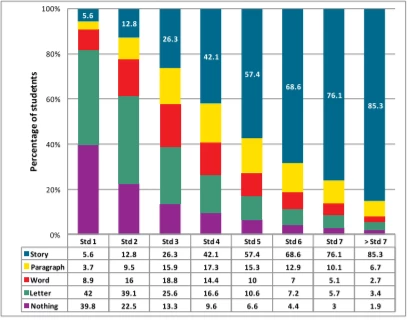

- Local conditions in the new context: In Tanzania – especially rural Tanzania – most students are far behind the curriculum. As the latest Uwezo report for Tanzania tells us: “Only one in four children in Standard 3 can read a Standard 2 story in Kiswahili. … Four out of ten children in Standard 3 are able to do multiplication at Standard 2 level.” The same study shows large variation by grade:

Source: Uwezo 2013

- Evidence for behavior change: A growing collection of studies point to the returns to interventions that help learners receive instruction at their level. Evidence from splitting classes by ability in Kenya, re-organizing classes by ability for an hour a day in India, providing teaching assistants to help the lowest performers in Ghana, and others. So there is broad evidence that students respond to this type of intervention.

- Possibility of implementation: I’m skeptical of the possibility of effectively scaling dedicated computer centers in rural Tanzania right now. The original program in India was in urban Delhi, and a previous, successful technology-aided instruction program in India was also in a city. I’m happy to be proven wrong, but I suspect that Step 4 is where adaptation would stop making sense in this case.

Evidence from one context can be clearly be useful in other contexts. But translation isn’t automatic. This four-step framework can be useful in figuring out how likely that translation is to work.

Bonus reading: Every regular Development Impact contributor has written on this issue. Here are a few of them:

- Goldstein: “What’s wrong with how we do impact evaluation?” (February 2016)

- Carranza & Goldstein: “Getting beyond the mirage of external validity” (May 2015)

- Friedman: “External validity as seen from other quantitative social sciences - and the gaps in our practice” (May 2014)

- Özler: “Learn to live without external validity” (November 2013)

- McKenzie: “Questioning the External Validity of Regression Estimates: Why they can be less representative than you think.” (September 2013)

Join the Conversation