Since I wrote this post, RISE moved all the papers and videos from this conference, so most of the links below no longer work. The papers and videos are now available here.

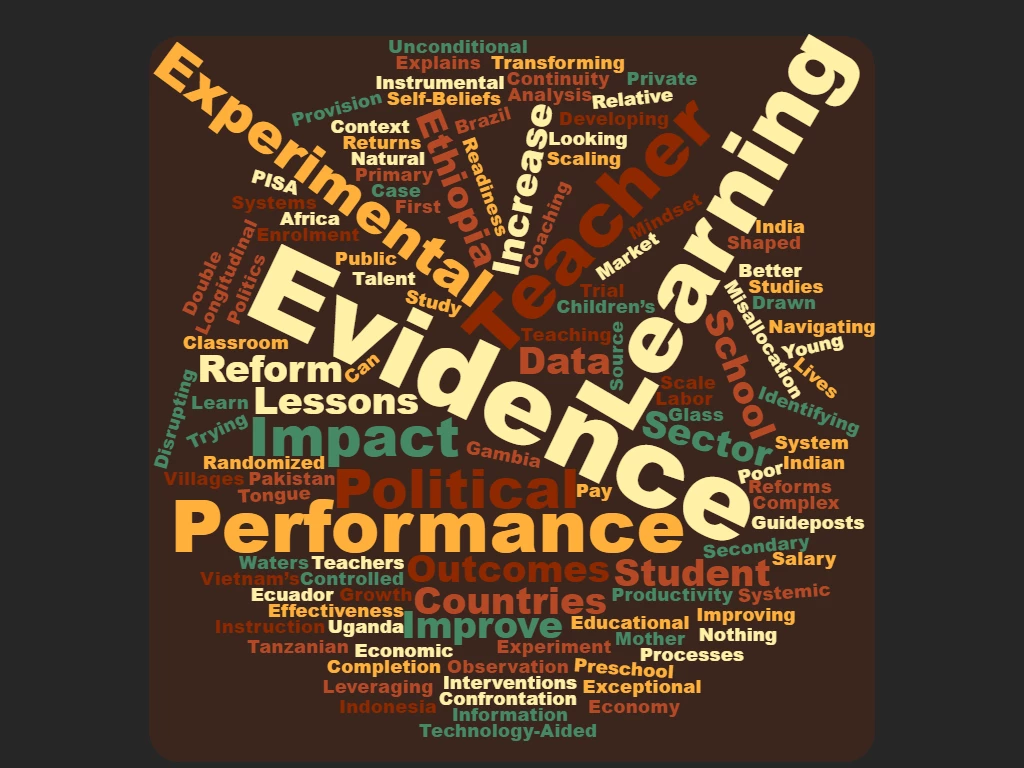

RISE – Research on Improving Systems of Education – seeks to answer the question, “How can education systems be reformed to deliver better learning for all?” As Justin Sandefur said in his opening remarks, “we need more than just piecemeal research and piecemeal reform.” How? “Invest over the long-term in real, cutting-edge, new empirical research from the all-star teams you’re going to hear from over the next couple of days.” The whole two-day conference is available for online streaming ( Day 1 and Day 2); the full program has links to many of the papers.

Here are some of the greatest hits among the research papers presented, including a bonus track that wasn’t on the program (at the end of the pedagogy section). If you saw a paper you enjoyed and it isn’t below, please add it in the comments!

Politics of Reform

- Recent dramatic improvements in learning outcomes in Ecuador hinged on 5 key reforms: “Higher standards for new recruitment, higher standards for entry into teacher training, regular evaluation of individual teacher performance, promotions based on tested competency rather than years of service, and dismissal from the civil service after multiple poor performance evaluations.” Schneider, Estarellas, & Bruns identify 5 political advantages that let the government get those reforms through: “strong public support grounded in a pervasive sense of education in crisis…, sustained presidential support, the commodity boom of the 2000s, continuity in the government reform team, and communications strategies that built popular sympathy for the government position against union efforts to block reforms.” [paper; video of talk @7m]

- Providing report cards on student test scores to both parents and schools that showed performance within the school and across schools led to big increases in test scores for private school students. Giving report cards just to schools didn’t make a difference. The result seems to be from parents moving kids to better quality private schools (rather than improvements in quality of the current schools) (Afridi, Barooah, & Somanathan) [paper]

- In Sindh, Pakistan, the government provided public resources to private schools, resulting in big increases in enrollment and test scores for both girls and boys. Barrera-Osorio et al. then estimate how private school entrepreneurs choose what private school characteristics to offer [paper; video of talk @7m]

- In Punjam, Pakistan, teacher value added is high, but teacher characteristics (including the first years of experience and content knowledge) explain little of it. In the public sector, cutting teacher wages by 35 percent did not affect teacher value added (Bau & Das) [paper; video of talk @28m]

- What’s the best way to improve children’s school readiness? The Gambia invited researchers to test two alternative methods, community-based centers in some communities and kindergartens with upgraded quality in others. Neither improved readiness on average, but the upgraded kindergartens were better for the least advantaged children (Blimpo et al.). [paper; video of talk @50m]

- Working kids who can’t do “school math” can still sometimes do serious arithmetic in market settings (including hypothetical situations), from survey work in West Bengal and in Delhi, India. [video of talk @4h38m]

- How much value does a good teacher add in Uganda? Using “random assignment of students to classrooms within schools,” Buhl-Wiggers et al. find that a 1 standard deviation “increase in teacher quality leads to at least a 0.14 SD improvement in student performance on a reading test at the end of the year.” That’s in classes with 80 students on average. [paper; video of talk @5h0m] This builds on the data from an experiment detailed in another paper on improving literacy instruction.

- Is it possible to talk about learning gains in a way that’s more accessible to policymakers than standard deviations? Evans (me!) and Yuan propose the Equivalent Years of Schooling (EYOS) measure, based on data from 5 low- and middle-income countries. “One standard deviation gain in literacy skill is associated with between 4.7 and 6.8 additional years of schooling” and “pedagogical improvements…[have] an average effect size of 0.13 standard deviation, which means these interventions help learn what they would normally learn in between 0.6 and 0.9 years of business-as-usual schooling.” [paper; video of talk @5h21m]

- Are all teachers putting in more effort than average? In Uganda, “teachers tend to rate ability, effort, and job satisfaction more positively for themselves than for other teachers.” It’s worst for new teachers and for the teachers who actually put in the least effort (Habyarimana, Kacker, & Sabarwal). [paper; video of talk @5h44m]

- Learning first in mother tongue results in higher math scores even after students transition into English instruction in Ethiopia (Seid). [paper; video of talk @6h54m] Earlier work from the same author suggests that mother tongue instruction in Ethiopia “increased the probabilities of both enrollment in primary school and whether a child attends the ‘right’ grade for her/his age, and the effects are relatively stronger for kids in rural areas.”

- A single 1.5 hour “Grow Your Mind” session in Peru taught secondary school students that their “abilities are not fixed” and that with practice, their brains “will grow stronger.” The result? “At a cost of just $0.20 per pupil,” the intervention resulted in “increased Mathematics test-scores (by 11-24% s.d.), higher pupil aspirations and increased teacher effort” (Outes, Sanchez, & Vakis). [paper; video of talk @7h15m]

- Providing teachers with feedback on how they’re using classroom time and “access to expert coaching” delivered via Skype increased student learning on a national exam (Bruns, Costa, & Cunha). [video of talk @7h41m]

- Longitudinal data from Ethiopia suggest that preschool participation has a large impact on secondary school completion; but only one-fourth of Ethiopian children – mostly the wealthy – get access to preschool (Woldehanna & Araya). [paper; video of talk @2h2m]

- A technology-aided after-school instruction program in India led to big gains in math and language (Muralidharan, Singh, & Ganimian). [paper; video of talk @2h22m] A while back, I wrote a summary blog post on this paper; later I wrote some thoughts on scalability. Ganimian highlighted here that the technology works online and offline and on a variety of platforms, so it’s potentially scalable beyond the urban Delhi experimental site. He also reminded us that Appendix B of this paper has an extensive review of ICT interventions in education, in both rich and poor countries.

- Doubling teacher pay in Indonesia increased teacher satisfaction but not their effort (de Ree et al.). [paper; video of talk @2h43m]

- Why does Vietnam do so well in education relative to other countries? Decompositions suggest that it’s not because of household or learner characteristics, but rather because Vietnam has highly productive schools (Glewwe, Lee, & Vu). [paper; video of talk @3h26m]

Join the Conversation