The discount rate used by individuals to trade off utility in the future against utility today is a fundamental parameter of decision theory. It is typically elicited in surveys by asking individuals to make choices between receiving an amount today, and a different amount at some point in the future. There are lots of key design issues involved in doing this (e.g. whether these can be hypothetical choices or need to be incentivized, making sure the transactions costs don’t differ between amounts today and in the future, dealing with trust issues (maybe I look like I have a high discount rate because I don’t trust you to pay me in the future), etc. But the key point I want to discuss today is the extent to which these preferences are stable over time – that is, if I measure your discount rate today, and I come back and measure it in a subsequent survey, will I get similar results?

Knowing the answer is important for at least two reasons. First, from both a theory and prediction point of view, if individuals change their discount rates often, then this makes modelling decisions much more difficult. Second, from a practical point of view, if discount rates are deep stable parameters, then maybe it is ok not to measure them in a baseline survey (that may be already very long with other questions, or may come from a short application form that can’t do this), and instead collect them in a follow-up survey and assume they are time-invariant.

Evidence on time-invariance

A study by Meier and Sprenger forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics provides some evidence that is relatively encouraging for the idea that these are quite stable parameters.

Their study population consists of low-income adults (average income US$16,000 per year) from Boston who came to get tax assistance from a program run by the City of Boston in 2007 or 2008. Although this is a very specialized sample, a nice feature is that the individuals granted access to their tax filing data, allowing the researchers to see how changes in income, unemployment, and family composition affect time preferences. There are 1684 participants who came in at least one of the two years, and a small panel of 250 individuals who came both years.

Individuals were given three multiple price lists, and asked to make a total of 22 choices between a smaller reward X (ranging from $14 to $49) in period t (either today, or one month), and $50 in period t+6 months (i.e. 6 or 7 months from now). 10 percent of individuals were randomly chosen to be paid one of their 22 choices to provide some incentive for truthful choice. To ensure credibility of the payments, money orders were filled out on the spot for the winning amounts and put in labeled, pre-stamped envelopes and then sealed, with the payment guaranteed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. All payments were sent by mail to equalize transaction costs across the choices.

So what do they find?

Evidence against time invariance

A new paper by Dean and Sautmann, to be presented this week at the BREAD conference offers a less sanguine assessment of the stability of time preferences. They use a panel data set of 1017 household heads in Bamako, Mali. The underlying survey is from a ongoing randomized trial for a health care program for children. This paper therefore provides a nice example of something I have previously blogged about, which is thinking about creative ways to get more than one research project out of an evaluation.

They visit households weekly, and give them multiple price list experiments asking them to choose between payoffs now vs in the next week, or in the next week vs the one after, with 8 pairs of choices for each. One decision was randomly selected for payout, with subjects either then getting the money or a written receipt saying when they would get the money, with the weekly visits making transaction costs low and trust high.

What do they find?

So what should we make of these two studies together when thinking about the time consistency of preferences? It seems that there is certainly a strong common signal over time, even when measured a year apart, so that on average I would expect the group of more impatient people today to also appear more impatient in the future. So if your goal is to do analysis where you are splitting people into more or less patient groups, it seems there is some common signal there. But it also seems clear that a number of people do change their choices from one survey round to the next, and that this is probably not just random noise, but can be systematically related to shocks occurring to them. This does suggest one should be very cautious about using discount rates collected in follow-up rounds of randomized experiments and assuming they are time invariant, since to the extent that the experiment affects liquidity constraints and protection against shocks, it may change choices.

Knowing the answer is important for at least two reasons. First, from both a theory and prediction point of view, if individuals change their discount rates often, then this makes modelling decisions much more difficult. Second, from a practical point of view, if discount rates are deep stable parameters, then maybe it is ok not to measure them in a baseline survey (that may be already very long with other questions, or may come from a short application form that can’t do this), and instead collect them in a follow-up survey and assume they are time-invariant.

Evidence on time-invariance

A study by Meier and Sprenger forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics provides some evidence that is relatively encouraging for the idea that these are quite stable parameters.

Their study population consists of low-income adults (average income US$16,000 per year) from Boston who came to get tax assistance from a program run by the City of Boston in 2007 or 2008. Although this is a very specialized sample, a nice feature is that the individuals granted access to their tax filing data, allowing the researchers to see how changes in income, unemployment, and family composition affect time preferences. There are 1684 participants who came in at least one of the two years, and a small panel of 250 individuals who came both years.

Individuals were given three multiple price lists, and asked to make a total of 22 choices between a smaller reward X (ranging from $14 to $49) in period t (either today, or one month), and $50 in period t+6 months (i.e. 6 or 7 months from now). 10 percent of individuals were randomly chosen to be paid one of their 22 choices to provide some incentive for truthful choice. To ensure credibility of the payments, money orders were filled out on the spot for the winning amounts and put in labeled, pre-stamped envelopes and then sealed, with the payment guaranteed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. All payments were sent by mail to equalize transaction costs across the choices.

So what do they find?

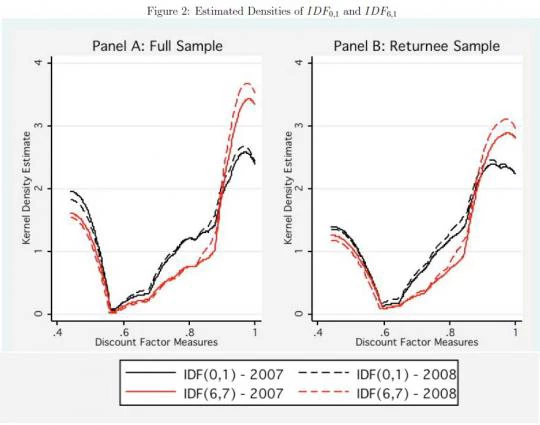

- Aggregate choice profiles over intertemporal payments are indistinguishable across the two years of the study. This is true for the full sample (panel A), and for the subsample that is present in both years (panel B). Note this figure also shows evidence of present bias (higher discount rates when comparing today vs 1 month from now to 6 vs 7 months), with this present bias being stable over time on aggregate.

- At the individual level, the one-year correlation in the discount factor is 0.4, and 43% of individuals exhibit identical switching points, and 50% have monthly discount factors within 0.025 of each other in the two years.

- Some individuals do show instability in their measured preferences, but this is not related to changes in income, unemployment or family composition.

Evidence against time invariance

A new paper by Dean and Sautmann, to be presented this week at the BREAD conference offers a less sanguine assessment of the stability of time preferences. They use a panel data set of 1017 household heads in Bamako, Mali. The underlying survey is from a ongoing randomized trial for a health care program for children. This paper therefore provides a nice example of something I have previously blogged about, which is thinking about creative ways to get more than one research project out of an evaluation.

They visit households weekly, and give them multiple price list experiments asking them to choose between payoffs now vs in the next week, or in the next week vs the one after, with 8 pairs of choices for each. One decision was randomly selected for payout, with subjects either then getting the money or a written receipt saying when they would get the money, with the weekly visits making transaction costs low and trust high.

What do they find?

- Like the above paper, they find that there is persistence in choices – between 64 and 69 percent make the same choice in one week as they did in the week before, with it being roughly symmetric whether those who didn’t were more patient or less patient.

- However, they find that the discount rate is related to whether or not an individual has just suffered an adverse shock – using individual fixed effects, household heads are more impatience if they have just experienced an adverse shock. The current version of the paper is not that clear to me in terms of how large in magnitude this effect really is in practice though, only that it is statistically significant. Section 6 of the paper has a summary of other work on this topic, including a summary of a new paper that finds people appear to be more present-biased right before pay-day than right afterwards.

So what should we make of these two studies together when thinking about the time consistency of preferences? It seems that there is certainly a strong common signal over time, even when measured a year apart, so that on average I would expect the group of more impatient people today to also appear more impatient in the future. So if your goal is to do analysis where you are splitting people into more or less patient groups, it seems there is some common signal there. But it also seems clear that a number of people do change their choices from one survey round to the next, and that this is probably not just random noise, but can be systematically related to shocks occurring to them. This does suggest one should be very cautious about using discount rates collected in follow-up rounds of randomized experiments and assuming they are time invariant, since to the extent that the experiment affects liquidity constraints and protection against shocks, it may change choices.

Join the Conversation