This is the sixth in our series of posts by graduates on the job market this year.

Tax enforcement is a central public finance issue in developing countries. Barriers to collecting tax revenue can severely constrain funding for basic public services and investments, and pervasive tax evasion can cause significant distortions in the economy. In my job market paper (“ Consumers as Tax Auditors ”) I use quasi-experimental evidence to evaluate a program to help governments collect taxes, by incentivizing consumers to monitor firms.

I examine firm-level compliance in a particularly challenging context: sales tax on final consumer transactions. When a consumer makes a purchase, she usually has no incentive to ask for a receipt, which is a key part of the paper trail for enforcement ( Pomeranz, 2013). What’s more, there are typically a large number of small firms that the government needs to monitor. For all other links in the supply chain, Value Added Taxes (VAT) create built-in incentives that help ensure compliance in transactions between firms. But the supply chain has a “last mile problem:” at the final consumer stage, the VAT’s self-enforcing incentives break down since consumers derive no direct monetary benefit from collecting receipts.

In order to address this problem, some countries have introduced policies that incentivize consumers to ask for receipts for their purchases. I study a program from the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil – Nota Fiscal Paulista (NFP) – that gives tax rebates and lottery tickets for consumers who collect receipts. A concern with such a self-enforcing approach is the possibility of collusion between the consumer and the firm: after all, the reward the government offers is lower than the tax paid by the firm, so the firm could potentially propose a discount for consumers that forgo receipts.

I examine how these incentives affect the reported revenue of establishments and consumer participation using a new data set I have constructed from anonymized administrative records of over 1 million establishments, 40 million consumers and 2.7 billion receipts.

The program:

the rewards program from Sao Paulo was introduced in October 2007. It leverages the new availability of information technology in the developing world, and the fact that consumers in Brazil often provide their ID numbers when shopping. As establishments were mandated to report all receipts they issue electronically to the tax authority, this program added the option to insert an individual ID number into each receipt, and created tax rebates for consumers who ask for receipts and who provide their ID numbers to be reported on these receipts. In order to collect rewards and participate in monthly lotteries consumers need to create an online account at the tax authority’s website, where they can also cross-check receipts reported by establishments and file complaints. The program is highly salient: by the end of 2011, 40 million consumers have asked for receipts more than once, and 13 million people have created online accounts at the tax authority’s website.

The impact of consumer monitoring on establishment compliance:

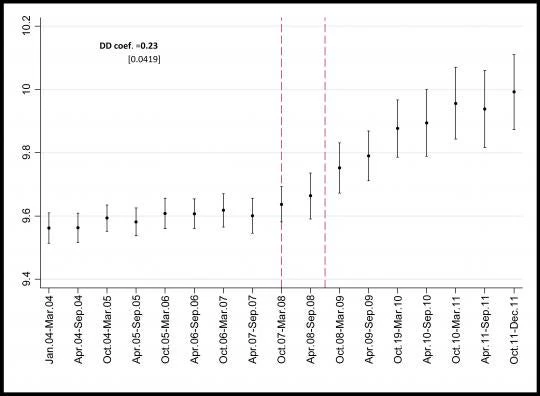

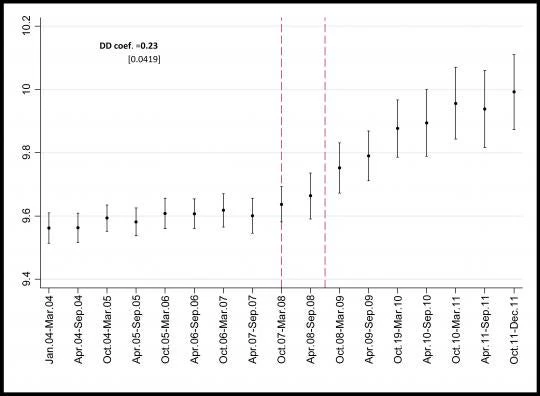

In order to measure the impact of the program on establishment reported revenue I exploit variation in treatment intensity across sectors using a difference in differences research design. Since the program is targeted to final consumers, I compare retail sectors (that sell mostly to final consumers) with wholesale sectors (that sell mostly to other establishments). I estimate that the program increased the revenue reported in retail by at least 23% over four years.

Differences in log reported revenue between retail and wholesale sectors - coefficients for 6-month time bins (red lines indicate program implementation)

Why do we see this increase in reported revenue? I exploit heterogeneity across establishments to shed light on mechanisms. The estimated effect is stronger for sectors with a high volume of transactions and small receipt values, consistent with there being fixed costs to negotiating collusive deals to avoid issuing receipts. Moreover, the effect of the program has an inverted-U shape with respect to establishment size, consistent with a higher baseline level of compliance among larger firms, and shifts in audit probability from consumer monitoring that increase in firm size. One concern with such a program is that it might cause employers to shut down or shed employees, but I find that the increase in compliance – and therefore in the effective tax rate – did not affect exit or employment decisions during the period of analysis.

Impact of incentives on consumer monitoring: the results above seem to imply that consumer monitoring can increase firm compliance. But how does consumer monitoring respond to the policy incentives? I use consumer-level data to investigate whether behavioral considerations can amplify their response to the rewards program. I compare lottery winners and non-winners with the same odds of getting a prize in an event study research design to show that consumers condition their participation on past lottery wins. Consumers may use past wins as a signal of their likelihood of getting a lottery prize, which would be consistent with misperception of randomness and the use of heuristics in making choices under uncertainty.

Even small prizes generate significant and steady increases in the number of receipts for which consumers ask, and in the number of different business from which they ask for receipts. The evidence on lotteries complements existing findings in the literature on the behavioral effects of lotteries. These behavioral tendencies could be being leveraged to improve tax policy in the context I study.

Number of receipts for which consumers ask after a lottery win (x-axis indicates number of months before/after a lottery)

Conclusion: Evidence suggests that the policy of creating incentives for consumers to collect receipts is an effective way to improve compliance by establishments. In a cost-benefit analysis I find that consumer rewards can potentially be a cost-effective way to improve firm-level compliance, and could perhaps be made more cost-effective by lowering participation costs and relying more on lotteries. The findings of the paper have broader implications for self-enforcing policies and consumer-rewards programs beyond the Sao Paulo experience. Evidence presented in the paper is consistent with the idea that collusion is a potential barrier to the effectiveness of a self-enforcing reward system when there is scope for a mutually beneficial deal. In addition, it provides novel direct evidence of consumer participation responses to lottery rewards, which is the most common reward used by other government programs. Moreover, since information technology made it relatively easy to reach a large number of people at a low cost, this study sheds light on the effectiveness of a type of participatory program that may become a relevant law enforcement tool.

Joana Naritomi is a PhD student at Harvard University and is on the job market this year. Her primary research interests are public finance questions in the context of developing countries.

Tax enforcement is a central public finance issue in developing countries. Barriers to collecting tax revenue can severely constrain funding for basic public services and investments, and pervasive tax evasion can cause significant distortions in the economy. In my job market paper (“ Consumers as Tax Auditors ”) I use quasi-experimental evidence to evaluate a program to help governments collect taxes, by incentivizing consumers to monitor firms.

I examine firm-level compliance in a particularly challenging context: sales tax on final consumer transactions. When a consumer makes a purchase, she usually has no incentive to ask for a receipt, which is a key part of the paper trail for enforcement ( Pomeranz, 2013). What’s more, there are typically a large number of small firms that the government needs to monitor. For all other links in the supply chain, Value Added Taxes (VAT) create built-in incentives that help ensure compliance in transactions between firms. But the supply chain has a “last mile problem:” at the final consumer stage, the VAT’s self-enforcing incentives break down since consumers derive no direct monetary benefit from collecting receipts.

In order to address this problem, some countries have introduced policies that incentivize consumers to ask for receipts for their purchases. I study a program from the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil – Nota Fiscal Paulista (NFP) – that gives tax rebates and lottery tickets for consumers who collect receipts. A concern with such a self-enforcing approach is the possibility of collusion between the consumer and the firm: after all, the reward the government offers is lower than the tax paid by the firm, so the firm could potentially propose a discount for consumers that forgo receipts.

I examine how these incentives affect the reported revenue of establishments and consumer participation using a new data set I have constructed from anonymized administrative records of over 1 million establishments, 40 million consumers and 2.7 billion receipts.

The program:

the rewards program from Sao Paulo was introduced in October 2007. It leverages the new availability of information technology in the developing world, and the fact that consumers in Brazil often provide their ID numbers when shopping. As establishments were mandated to report all receipts they issue electronically to the tax authority, this program added the option to insert an individual ID number into each receipt, and created tax rebates for consumers who ask for receipts and who provide their ID numbers to be reported on these receipts. In order to collect rewards and participate in monthly lotteries consumers need to create an online account at the tax authority’s website, where they can also cross-check receipts reported by establishments and file complaints. The program is highly salient: by the end of 2011, 40 million consumers have asked for receipts more than once, and 13 million people have created online accounts at the tax authority’s website.

The impact of consumer monitoring on establishment compliance:

In order to measure the impact of the program on establishment reported revenue I exploit variation in treatment intensity across sectors using a difference in differences research design. Since the program is targeted to final consumers, I compare retail sectors (that sell mostly to final consumers) with wholesale sectors (that sell mostly to other establishments). I estimate that the program increased the revenue reported in retail by at least 23% over four years.

Differences in log reported revenue between retail and wholesale sectors - coefficients for 6-month time bins (red lines indicate program implementation)

Why do we see this increase in reported revenue? I exploit heterogeneity across establishments to shed light on mechanisms. The estimated effect is stronger for sectors with a high volume of transactions and small receipt values, consistent with there being fixed costs to negotiating collusive deals to avoid issuing receipts. Moreover, the effect of the program has an inverted-U shape with respect to establishment size, consistent with a higher baseline level of compliance among larger firms, and shifts in audit probability from consumer monitoring that increase in firm size. One concern with such a program is that it might cause employers to shut down or shed employees, but I find that the increase in compliance – and therefore in the effective tax rate – did not affect exit or employment decisions during the period of analysis.

Impact of incentives on consumer monitoring: the results above seem to imply that consumer monitoring can increase firm compliance. But how does consumer monitoring respond to the policy incentives? I use consumer-level data to investigate whether behavioral considerations can amplify their response to the rewards program. I compare lottery winners and non-winners with the same odds of getting a prize in an event study research design to show that consumers condition their participation on past lottery wins. Consumers may use past wins as a signal of their likelihood of getting a lottery prize, which would be consistent with misperception of randomness and the use of heuristics in making choices under uncertainty.

Even small prizes generate significant and steady increases in the number of receipts for which consumers ask, and in the number of different business from which they ask for receipts. The evidence on lotteries complements existing findings in the literature on the behavioral effects of lotteries. These behavioral tendencies could be being leveraged to improve tax policy in the context I study.

Number of receipts for which consumers ask after a lottery win (x-axis indicates number of months before/after a lottery)

Conclusion: Evidence suggests that the policy of creating incentives for consumers to collect receipts is an effective way to improve compliance by establishments. In a cost-benefit analysis I find that consumer rewards can potentially be a cost-effective way to improve firm-level compliance, and could perhaps be made more cost-effective by lowering participation costs and relying more on lotteries. The findings of the paper have broader implications for self-enforcing policies and consumer-rewards programs beyond the Sao Paulo experience. Evidence presented in the paper is consistent with the idea that collusion is a potential barrier to the effectiveness of a self-enforcing reward system when there is scope for a mutually beneficial deal. In addition, it provides novel direct evidence of consumer participation responses to lottery rewards, which is the most common reward used by other government programs. Moreover, since information technology made it relatively easy to reach a large number of people at a low cost, this study sheds light on the effectiveness of a type of participatory program that may become a relevant law enforcement tool.

Joana Naritomi is a PhD student at Harvard University and is on the job market this year. Her primary research interests are public finance questions in the context of developing countries.

Join the Conversation