This is 24th in the series of Job Market Posts in 2023.

Parental beliefs about child academic achievement influence educational investment decisions and eventual outcomes. Much of the research in this area explores the role of information frictions, showing that parents update beliefs in response to information, with positive consequences for investments and child performance (Dizon-Ross, 2019; Barrera-Osorio et al., 2020; Gan, 2021). In other words, information shifts beliefs, and beliefs shift investments.

Related research points to socioeconomic disparities in parental beliefs about various features of the human capital production function, such as the importance of early investments or how investments translate into outcomes (Boneva and Rauh, 2018; Cunha et al., 2013, 2022, 2023; List et al., 2021). However, little research explores whether and how parental beliefs about child academic achievement themselves differ along socioeconomic lines; any such disparities could similarly contribute to well-documented disparities in investments along socioeconomic lines.

My job market paper draws on original and existing data from India (IHDS), the USA (ECLS-K), Kenya (KLPS), and Ghana (GSPS) to (1) document substantial disparities in parental beliefs along socioeconomic lines, (2) provide evidence that socioeconomic status causally shapes parental beliefs, and (3) explore potential channels through which socioeconomic status may shape parental beliefs.

(1): Socioeconomic disparities in beliefs: Cross-sectional evidence

The study first documents a robust relationship between socioeconomic status and parental beliefs about child academic achievement. The datasets used for the analysis feature three key components: (1) parental beliefs about child academic achievement, (2) actual child performance in math and reading, and (3) household socioeconomic status.

Parental beliefs are primarily characterized as binary indicators for whether parents believe their child is above or below average academically. These measures are based on responses parents provide when asked whether their child is an average, above average, or below average student (India, Kenya) or how their child learns, thinks, and solves problems compared to other children (USA). In Ghana, parents were asked to report the decile rank they believe their child attained on a survey-based test; this more granular measure is analyzed alone and is converted to the above/below average format for comparability. Finally, beliefs are characterized as accurate, overestimates, or underestimates by comparing stated beliefs to actual child performance.

The results indicate that socioeconomically advantaged parents are more likely to believe their child is above average compared to socioeconomically disadvantaged parents, and vice versa. For example, above-average beliefs are 11% (Kenya) to 60% (India) more likely among high consumption parents, while below-average beliefs are 13% (Kenya) to 45% (USA) more likely among low consumption parents.

Importantly, these patterns persist when accounting for child performance, suggesting that disparities in beliefs by socioeconomic status outpace any disparities in performance along these same lines. These disparities appear common across all four countries, and emerge for different dimensions of socioeconomic status, including measures that speak to economic circumstances (consumption, income), educational attainment, and social identity (caste, race).

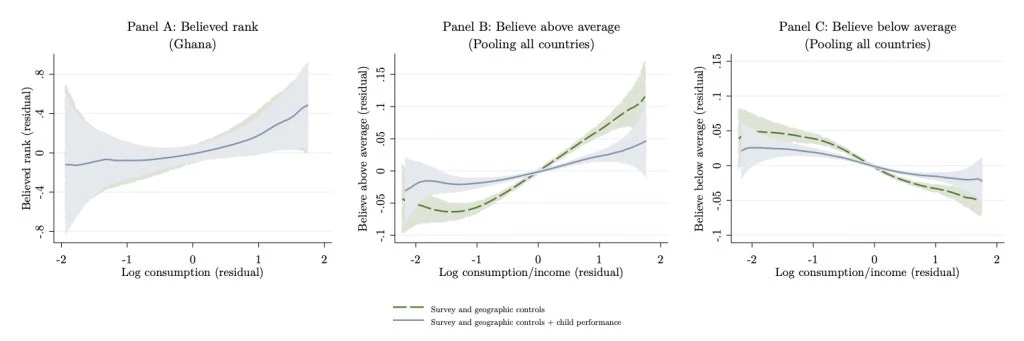

The figure below illustrates these patterns. Each panel presents local linear regressions of beliefs on household consumption or income, using residual measures after controlling for a minimal set of survey and geographic characteristics (dashed green lines) or additionally controlling for child performance, age, and gender (solid blue lines). As household consumption increases, Ghanaian parents are more likely to believe their child has attained a higher relative rank (Panel A). Similar patterns emerge for the binary measures: Pooling across all four countries, the likelihood of above-average beliefs rises steadily with household consumption/income (Panel B), with the reverse for below-average beliefs (Panel C). These relationships attenuate, but largely persist when accounting for actual child performance, suggesting systematic disparities in parental beliefs. OLS estimates confirm these patterns: Controlling for child and school characteristics in the USA, a doubling of household income among parents is associated with a two-percentage point decline in the likelihood of below-average beliefs (a 15% decline relative to the mean). In India, a doubling of household consumption is associated with a five-percentage point (25%) increase in the likelihood of above-average beliefs.

Last, parental beliefs correlate with educational investments in all contexts, and with educational expectations and child self-confidence where available. Controlling for relevant socioeconomic factors, such as household consumption and parents’ education, educational investments are between 0.13 and 0.18 standard deviations higher among parents with above-average beliefs compared to those with average beliefs; to put this in perspective, investment gaps across high- and low-consumption parents range from 0.4 to 0.65 standard deviations across contexts. [1] Though these results only reflect correlations, they are nevertheless consistent with research showing that beliefs causally influence actual investment decisions.

(2): Socioeconomic status shapes parental beliefs: Causal evidence

These patterns could simply reflect a correlation between socioeconomic status and parental beliefs – arguably still of policy interest – or could reflect a causal relationship, where some features of socioeconomic status fundamentally shape parental beliefs. I use two different strategies to explore the latter hypothesis, each leveraging variation that speaks to different dimensions of socioeconomic status.

In India, I explore the impact of positive and negative rainfall shocks on parental beliefs among rural households using a household fixed effects specification. Agricultural income declines substantially, above-average beliefs become five-percentage points less likely (p<0.05), and underestimation becomes eight-percentage points more likely (p<0.05) in response to adverse rainfall in the previous rainfall year. These findings suggest that parental beliefs respond to changes in transient economic circumstances, suggesting a causal link between the economic dimension of socioeconomic status and parental beliefs.

In Kenya, I explore how randomized receipt of childhood deworming in one generation impacts beliefs about children in the next generation. A body of research based on the parent sample in Kenya shows that additional exposure to deworming during childhood leads to a range of benefits in adulthood, including improvements in labor market outcomes, higher consumption and earnings, greater likelihood of urban migration, and lower child mortality in the next generation (Miguel and Kremer, 2004; Baird et al., 2016; Hamory et al., 2021; Walker et al., 2023). This collection of results reflects substantial improvements in outcomes related to and indicative of socioeconomic status. In the present study, I find that parents who were randomly assigned to receive additional years of childhood deworming are four-percentage points less likely to believe their child is below average (p<0.05) and 10 percentage points more likely to believe they will be above average in the future (p<0.05). Results persist for constructed measures of belief accuracy that implicitly account for any potential treatment effects of parent deworming on actual child performance: accurate beliefs are eight-percentage points more likely among treated parents (p<0.05), driven by a nine-percentage point decline in underestimation (p<0.05).

Together, these results lend support to the hypothesis that economic circumstances specifically (India) or socioeconomic status more broadly (Kenya) causally shape parental beliefs.

(3): Potential channels

Finally, the paper discusses and provides evidence for several mechanisms that might explain these empirical patterns. These include differential access to information, factors that may distort how information is incorporated (such as the influence of role models or prevailing stereotypes), psychological factors, or a behavioral (self-protective) response.

Evidence from an original survey experiment I conducted in partnership with a local organization among a sample of parents in Delhi, India shows that parents made more aware of their economic constraints report feeling less confident, while below-average beliefs are less likely among those encouraged that they have the resources to support their child. In Kenya, survey responses indicate that lower socioeconomic status parents disproportionately believe that external factors (rather than their child’s capabilities and effort) will determine eventual outcomes. Psychological factors may also play a role. Receipt of childhood deworming positively impacts various measures of psychological well-being in adulthood (Duhon et al., 2023). Further, depression, self-efficacy, stress, and hopelessness each correlate with their beliefs as parents.

While the analysis in this section of the paper is largely exploratory, the evidence points to several mechanisms that might explain these patterns and suggests promising avenues for future research.

Takeaways

This research provides novel evidence of disparities in parental beliefs along socioeconomic lines. To the extent that parental beliefs shape educational investment decisions and influence child motivation, confidence, and effort in the classroom, such disparities could contribute to and further reinforce socioeconomic inequalities in educational investments and outcomes.

Madeline Duhon graduated with her PhD in Economics at the University of California, Berkeley in 2022, and is currently a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Demography at the University of California, Berkeley

[1] A back of the envelope calculation based on estimates from Malawi (Dizon-Ross, 2019) suggests that providing parents with information that their child ranks 2.5 deciles higher than they thought (the average “error” among those who underestimate in Ghana, regardless of SES) could causally increase educational investments by up to 8%, equivalent to 12% of the high-low consumption gap in investments in Ghana.

Join the Conversation