Several recent studies have tried to get small firm owners to meet up with other firm owners, with the aim being that they can learn from one another. Effects to do so have had mixed success. They have been very successful in some cases, leading to improved business practices and profits (e.g. Cai and Szeidl, 2018); had more modest effects on diffusion of several business practices in others (e.g. Fafchamps and Quinn, 2016); with sharing of technology and practices limited by competition (e.g Hardy and McCasland, 2019) and mentoring by other firms having effects that do not persist over time (Brooks et al. 2018), or that do not show up at all (e.g. McKenzie and Puerto, 2020).

Two difficulties in scaling up such programs are (i) the organizational logistics of deciding which firms should meet with which other firms, and getting the firms to actually meet with one another; and (ii) understanding exactly what information and advice firms are providing to one another and ensuring it is helpful. This raises the question of whether you can help firms learn from their peers, without them actually having to physically meet with these peers – something of particular interest in the current environment of social distancing. Two recent working papers suggest two promising approaches that seem worth further exploration.

Sharing local best practices

A first approach is provided in a working paper by my colleague Bilal Zia and his co-authors Patricio Dalton, Julius Ruschenpohler and Burak Uras. Their idea is to share which practices successful peers have employed and how they have employed them. They work with traditional retail shops in Jakarta. The typical shop is run by a woman with 9 years education, and on average employs 2 workers, has been in business 13 years, and has monthly profits of just over 900 USD in PPP terms.

In a first phase, they conduct qualitative interviews with local firms to understand which business practices are being used, misconceptions about different practices, and implementation norms. They then use survey data to examine quantitively which business practices are most strongly associated with profits and sales. They put together business practices in five categories: record-keeping, financial planning, stocking-up, marketing, and joint decision-making, and use these to put together a handbook of best practices (available online here), and pictured below. The handbook goes through common misunderstandings (e.g. keeping records is hard for people without higher education); explains why it is important to use a practice (e.g. shops with written business records make 26% higher profits); sets out step by step instructions of how to do a practice (e.g. 9 steps for record-keeping) and ends with local tips (e.g. how to deal with the uncertainty of electricity bills in Jakarta, and why switching to a local voucher system works for a lot of firms).

They conducted a sample with 1,301 urban retail shops in Jakarta, of which 261 were a control group and 1,040 were offered a free copy of the handbook. Unsure of whether the handbook alone would be enough, they divided the handbook group into four groups of 260 firms:

· Handbook only – they just got this information from anonymized local peers, aggregated up in the form of this handbook.

· Handbook + documentary – they were also shown a 25 minute documentary in which successful peers explained their growth trajectory adopting the best practices in the handbook. 52% watched the documentary.

· Handbook + personal assistance: they received two half hour visits from a trained enumerator to provide specific help on adopting these practices. 77% got the first visit, and 68% both.

· Handbook + documentary + personal assistance: they got both of the above items.

The authors conduct follow-up surveys at 6 and 18 months after the intervention, reaching 92% at midline and 81% at endline, with attrition 2-3 p.p. lower for treated firms.

The main findings are:

1. Pure information alone from local peers has no significant impacts: the handbook alone has no significant impacts on adopting business practices (a typical 95% confidence interval is -2 p.p., +6p.p. change in practices), and no significant impacts on profits or sales.

2. Combining the handbook with the documentary and/or personal assistance does lead to significant improvements in business practices and in firm profits. Across five types of practices, point estimates are typically for 3-6 p.p. improvements in practices for those offered treatment – or if you think there are no impacts of the handbook alone and consider TOT for those who actually watched the video and got assistance, around 10-11 p.p. improvement for those getting both treatments. Firms assigned to all three treatments increase profits by 21%, or 191 USD PPP per month.

3. The main channels for improvements appear to be gains in response and process efficiency, rather than direct business expansion - firms are learning how to adjust stocks, keep better records, etc.

Benchmarking against the sales of other firms

A second idea of how to use information on other firms is through benchmarking. I have had discussions with project teams at various points about helping firms benchmark their management practices against those of other firms in their industry, but have not yet seen this tested. A more straight-forward approach that caught my eye is to simply have firms benchmark their sales. A working paper by Julia Seither tests this approach, using a sample of 315 small vendors in Maputo, Mozambique. 46% of the firm owners are female, with an average 8 years of schooling.

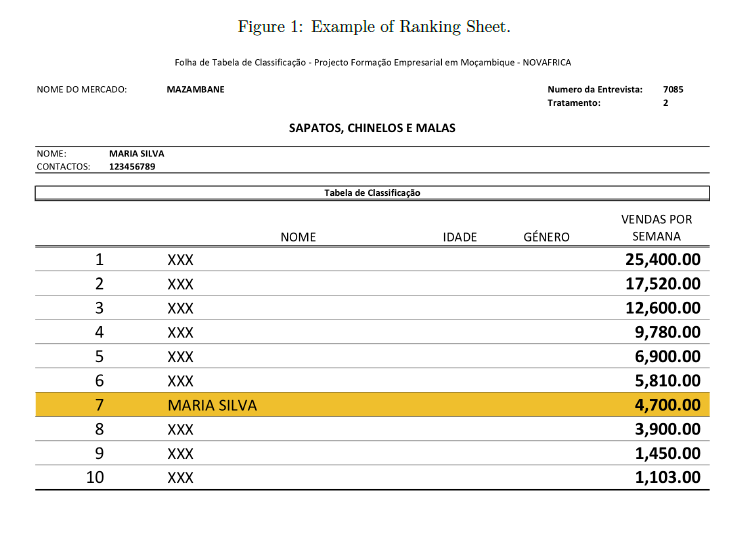

Two months after a baseline survey, 192 of the firms were randomly chosen to receive a ranked list of ten anonymous venders, including themselves, representing the full distribution of vendors in their sector. It highlights the owner’s own name and position, and then shows a firm per other decile, where the other firms are chosen to have the median sales for their respective decile within the sector. Hence all firms in the same sector in the treatment group are shown the same peers. The figure below shows how this was presented:

Half of those treated were also provided with the age and gender of the other firm.

Ex ante, it was unclear to me what to expect here. The author notes that this benchmarking could provide firm owners with new information about the highest levels of revenue attainable in their sectors, and thus, in particular, get low-performing firms to update their beliefs on the returns to effort. It may also spur them to exert more effort if they care about the relative standing itself. On the other hand, since the author documents that most firms do not have accurate beliefs about their position in the distribution, one could imagine that learning you are a low-performer could encourage low-performing firms to quit (as has been found with feedback in some business pitch competitions).

Impacts are monitored through two follow-up surveys: at four months and one year after the intervention, with response rates of 94% and 85% respectively. One nice feature is that in the second follow-up, to get at concerns of self-reporting of sales, enumerators monitored actual sales of the firm over an entire business day.

The main results are:

1. Low-performing (below median) firms increase effort when given this ranking information: they work 0.86 hours more per day than low-performers in the control group, exerting almost as much effort as high-performers in the control group. In contrast, high-performers exert less effort, working 0.5 hours less.

2. Low-performers significantly increase both self-reported profits, and self-reported and physically observed sales. Sales of low-performers more than double compared to low-performers in the control group, and self-reported profits are 54% higher.

3. There is suggestive evidence that impacts are higher when peer gender is observed

Promise and Caveats

Many small firm owners work really long hours, and may have limited networks with which to gather advice from others doing similar work – while competitive pressures may make firms reluctant to share with immediate neighbors anything they think is working well for them. This suggests there could well be a market failure in useful information that firm policy can help fill. Both the ideas above therefore seem worth replicating and testing further in other contexts. A few caveats/thoughts on this:

1. How long-lasting are these effects? The studies above document effects lasting to 12 months to 18 months post-intervention. We would like to know whether these effects last 3 or 5 years. However, even if they don’t, because these interventions have low marginal costs, they may not need to last long to still pass cost-benefit tests.

2. Sample sizes and effect sizes: performance outcomes in small firms are incredibly volatile, making it hard to detect impacts on profits and sales. We have many examples of studies with treatment and control sample sizes of a couple of hundred firms each which find insignificant results, but where confidence intervals allow for 25% or more increases in sales and profits. The benchmarking study has a treatment group of 192, with samples smaller still once one looks at low vs high-performers, and at whether the gender and age were provided or not. The effect size of a doubling in sales is really large relative to the increase in effort of 9%. So it would be nice to see future work that builds on these proof-of-concept papers use samples of 1000 or more firms in each group.

3. Is there a market solution? How much would firms be willing to pay for this handbook, or for this benchmarking analysis? In thinking about how such an approach could be scaled up to serve the thousands of small firms, it would be interesting for future work to test a market-based solution.

Join the Conversation