Have you ever waited more than one year for a first decision from a journal, which ended up being a one-paragraph letter from the editor that had little value and a review from one referee that read more like a summer book report than a referee report at a serious academic journal in economics? Me, too…

As disappointing as such experiences might be, one might wonder how common they are, whether they are more common in economics, whether the variance is high, why they happen, and whether they affect important outcomes, such as how influential the paper eventually is (assessed by citations in the future). A new paper by Hadavand, Hamermesh, and Wilson in the Journal of Economic Literature tries to answer some of these questions. Here is a quick summary of their findings and some additional thoughts.

The authors focus on detailed data from three of the five top 5 journals in economics, whose editors responded to their requests with detailed data for breaking down the process into paper in editor’s hands (including refereeing time) and paper in author’s hands (responding to requests for revise and resubmits). They also use some data from a few other journals that have decision times published online for the descriptive (how slow?) part of their analysis, but these data do not allow the breakdown of who is responsible for the delays (the authors also like to use eclectic language, such as dilatory, the usage of which was an order of magnitude more common in 1800 than in 2019). It is important to make it clear that the database of papers, then, are those (about 250) that did get published in a top 5 journal in 2012-2013 and does not include papers that got rejected at these journals and went to others or were rejected at other journals beforehand.

How slow?

The paper not only reports submission to acceptance (S-A) times but also submission to publication. I will ignore the latter here as instant online publication of accepted manuscripts has made it irrelevant.

· The average S-A was just under 25 months for papers in four of the top 5 in economics + The Review of Economics and Statistics in 2012-2013. The median was 21 months while a paper in the 90th percentile took 42 months to get accepted (see Table 1 in the paper).

· These figures contrast with 13, 12, and 22 for journals in political science and psychology, and 6, 5, and 9 for papers in Nature and PNAS.

· What will come to many as a surprise is that things did not improve for papers that were published in the same journals in 2020 (I would have preferred 2019 as a cleaner year of observation without the possible effects of the Covid-19 pandemic). The mean, median, and the 90th percentile figures were 26, 22, and 50 in econ. Given that a number of journals did streamline their processes in the past decade, this seems surprising. Apparently, upon hearing from one editor who said that their journal may have been slow in the past, but it no longer is, the authors did not have the heart to tell them that while the mean S-A was slightly lower, the mass at the right tail had increased at that journal. There is heterogeneity across (and within!) journals for sure: of the five econ journals in this part of the analysis, the median S-A increased in two, decreased in two, and was unchanged in one between 2012 and 2020.

· All in all, the fact that things have not improved by that much on average in 7-8 years, with the uncertainty for a submitting author actually increasing, is not encouraging news for the profession.

Who is responsible for the long slog?

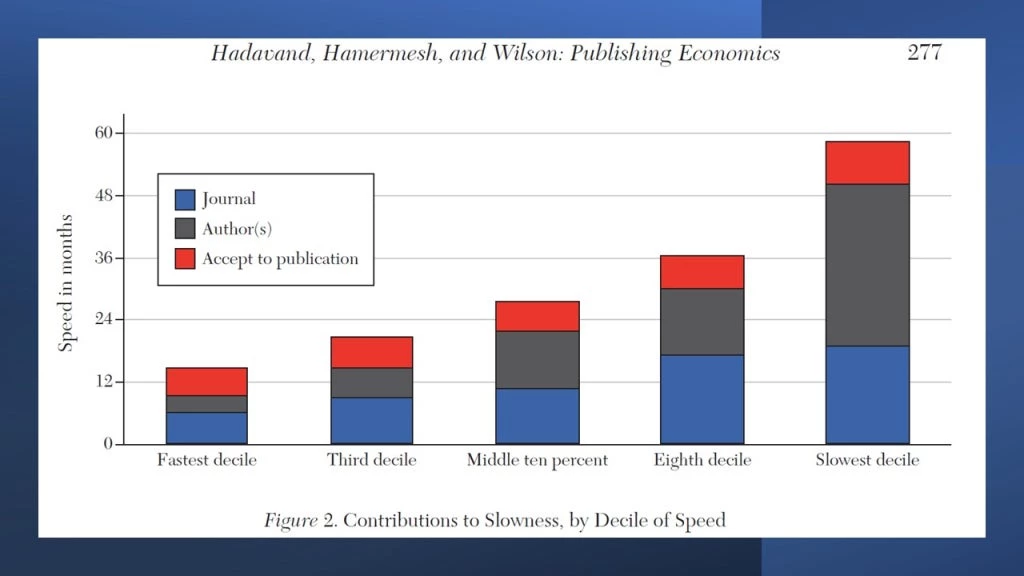

Table 2 in the paper reports that about a quarter of papers go through two rounds of submission (original submission and the revise and resubmit), 50% go through three (two R&Rs), and almost another quarter go through four rounds (three R&Rs!). The figure below shows how much total time the paper spends in editor’s hands (which includes refereeing time, and it would have been really nice to differentiate this) vs. the authors’ hands. It’s interesting to note that while the former dominates for the papers that go through the process faster, they are equal (roughly one year each) around the median. In the slowest decile of papers (from submission to publication), the paper spends more than two years with the author (after submission!) and close to two years with the editor/referee.

The variance in the overall S-A is high, at almost 17 months at all three journals. When this is decomposed, more than half of it is due to authors and about a quarter to the editors (and the remainder, i.e., the covariance between these two is positive, which makes sense, but not large). So, a lot of the delays in economics publishing are attributable to authors (purely descriptively and without any judgment! More on this later…). There is also large variation across journals: for example, the variance due to journal is 2% of the total for one of the three top-5 journals analyzed here, compared with 45% at another. The means and variances also differ substantially.

Are the delays serving a purpose?

This is the part of the paper that comes with caveats on causality, as the authors report conditional correlations between the number of rounds of submissions/time in X’s hands (X= author or editor) and Web of Science citations 8 years later (also checking Google Scholar citations for robustness). It is weird to see this type of analysis in 2024 rather than a natural experiment of some sort. The coefficient estimates are actually sizeable but also noisy, so combined with the uncertainty regarding causality, they should be taken with a large pinch of salt. The authors find two things:

1. More rounds of submissions are associated with more citations (about 20-25% by my reading). Once journal FE are included, the estimates for a fourth round (three revise and resubmits) is as important as a third round (compared to only two rounds).

2. Conditional on rounds of resubmissions, time in authors’ hands is negatively correlated with future citations. Some suggestive evidence that both of these findings are mostly due to non-theory papers…

This is admittedly the weakest and the speculative part of the paper: one gets the sense that the authors don’t really give a lot of credence to the idea that a good chunk of these papers that spend a lot of time at the authors’ hands being revised might need those extra bits of time and benefit from this additional work. For one of my recent publications with two reviewers, one referee report (for an R&R) was 10 pages – the responses ballooned the document to 30+. The extra bits of analysis, back and forth between the large number of co-authors, and people’s schedules all take time. Particularly because any R&R, especially one at a top journal, is high stakes, you want to cross all your Ts and dot all your Is before resubmission. No one wants to be rejected at this stage or necessarily get another time-consuming R&R: the aim is conditional accept with minor clean-up tasks…

The authors suggest, both on the conditional correlations being taken at face value, that while extra revisions are valuable, time with the authors is not (and perhaps even damaging). They use the fact that time with journal and time with author have a low correlation coefficient between them to support this hypothesis: I disagree with this argument. All (good or sub-par) original submissions may have trouble finding a good referee that is available, get them to do it in a timely fashion, who might then produce equally long reports regardless of quality (remember these are papers eventually published, so we’re not talking about the common advice of keeping it short for rejections). In my mind, it is more than plausible that papers get better through the revision process, with possibly both the requested revisions and extra effort spent on those revisions playing a role. This may be particularly true for empirical/experimental papers with (a) a lot of data that were not analyzed for the submitted manuscript, (b) have more follow-up rounds coming soon, and/or (c) can quickly collect more data to answer a certain question from the editor or a referee. I definitely know of papers that have been asked to do (and done) (c). I also know of authors who kept money for additional rapid data collection at hand just for that possibility. Like I said, when one of these editors say jump, most of us do…

None of this is to say that we do not procrastinate. And, as the authors state, given the large rewards at the end of the process, such procrastination is costly and difficult to explain. It is definitely not uncommon to hear researchers say that they are not going to get to an R&R anytime soon. Such statements can have perfectly good reasons behind them – already scheduled travel, responsibilities to co-authors, family responsibilities, illness/fatigue, and so on). I always tell them what Martin Ravallion used to tell me (and, of course, led by example): “You do not sit on R&Rs.” You should prioritize them as best as you can. As the authors state, it is unlikely that the work that needs to be done for an R&R is close to the full six months that 56% of the articles took from first decision to resubmission. There is possible prioritization at the margins and most of your colleagues (co-authors, department chairs, managers, and so on) will be understanding if you do this.

There is another reason as to why you should not take too long to resubmit your papers: editors change, and referees become unavailable for repeat duty on the same paper. The only paper with an R&R that then got rejected in my career is one where the editor changed, and the new editor did not care for the paper. The authors recount a similar story of a paper that was resubmitted 18 months after the first decision and promptly rejected by the new editor who was uninterested in the topic. So, there are multiple reasons to get your papers out as quickly as possible: (re)submit that paper right now. However, if you need a lot of time to respond thoroughly to each comment (hopefully the editor prioritized them for you and told you to ignore some), then, by all means, take that time.

In the end, however, I don’t think that this type of regression analysis of non-experimental data is the way to go regarding whether time spent with the editor, referee, or author leads to better outcomes, a better paper, better science, and policy. It would be good to get a large subset of the referee reports and authors’ responses for these papers, perhaps using ML and NLP techniques to analyze the text, to better understand how much authors were really procrastinating vs. addressing difficult requests. Did editors give clear instructions to the authors on how to address various comments or did they leave them to their own devices, who, in the absence of clear guidance, wasted time addressing every comment, however irrelevant they might have been for the final paper (the authors call this “reviewers acting as co-authors rather than gatekeepers.”)?

Some good news and possible solutions

Despite the fact that improvements at journals have not yet produced results on average, there is actually some good news. For example, the mean S-A for AER: Insights is four months: the median is also four and the 90th percentile is five months. When a paper in AEJ: Applied is cascading down from AER with referee reports, the S-A time (as well as its variance) seems substantially shorter than when it is submitted directly without prior review.

Here are some suggestions the authors have to reduce publication lags:

· Allow authors to choose a track: fast track with either a reject or accept (with minor modifications at most) or regular track with R&R added to the mix. The evidence from Economic Inquiry, a journal that has been doing this for a good while now is that the former is faster. Without any suggestion of causality, the authors think that this type of option could give under-pressure tenure-track assistant professors a good option. I am not sure how this works in equilibrium to be honest: it is a complicated optimization problem for both the journals and the submitters.

· Desk reject more: Current desk rejection rates are around 50-60%, while acceptance rates are under 10% in many cases. The authors reasonably speculate that perhaps the editors could have identified more papers that have no chance for publication at that venue, with a bit more effort. Given my experience with multiple papers that got rejected after a very long wait to first decision and referee reports of minimal value (especially these days where the editors are reportedly having more trouble finding suitable referees that are available to complete a review in a timely fashion), this does strike me as possibly a good idea. But it would mean more work for editors: maybe we need more (well-compensated) editors and less (unpaid) referees?

· Limit revision time: self-explanatory. Most letters from editors I get do suggest a timeline within which to resubmit and we generally try to keep to those deadlines. The question is whether those timelines should be shortened, with some flexibility for accommodating reasonable requests from authors. (Shorter resubmission windows but longer than 48-hour galley proofs, please!)

· Limit referee/editing time: The authors seem positive about this, suggesting that we give the referee, say, three months, and then drop them. However, if an editor has searched for weeks to find one referee, who is now non-compliant, they may be reluctant to drop that referee and search for another one. Also, relying on one referee is too idiosyncratic, so we’d need three reviewers on board, so that we can afford to drop one off. The authors argue that if the number of experts is so low that the editor cannot secure suitable referees, then the paper probably does not deserve publication in a general interest journal. Hmmm…

· Editors should do better: In the end, despite all of the above, the authors seem to conclude that it’s the editors who have enabled the current equilibrium of slow publishing to emerge and they are the ones with the real power and responsibility to change it. It is true that there is no escaping the fact that editors hold a lot of power. On the one hand, a good editor is quite successful in running a well-reputed journal and a tight ship, who is able to get good referees that prioritize their reviews. On the other, they have difficult jobs, with annual submissions to journals now in the thousands. Here are some ideas to consider: desk rejecting more papers; giving clearer instructions to referees; giving clear instructions to authors as to what it is they exactly need to do for a clear path to publication and, more importantly, what they should not do (“ignore half of referee 3’s comments,” “this issue is optional: address it if you can,” etc.); and perhaps even having a back and forth with the authors as to whether certain requests are doable within a reasonable amount of time. I would love to hear editors’ perspectives on this issue, many of whom, I suspect, are overwhelmed with the amount of work that they have and having difficulty herding cats (finding, guiding, and chasing referees).

On a final note, I find this JEL paper too focused on academic concerns: the problem of slow publications is primarily that of the assistant professor whose life hangs on the balance because of a pending decision at a journal pertinent to their context. I agree that this is stressful, but we also do these papers so that they can influence policy in a timely manner. Granted, the stakes in economics research are not as great as those in medical sciences, where some journals have extremely speedy tracks for results patients are waiting for, but we can do better. Before a paper ever arrives at an editor’s desk, it spends so much time with an author. Some of this is necessary planning and the need for follow-up surveys, but a lot of it is also strategic: many authors will park the first draft as a working paper and “workshop” it at various conferences and seminars; get it seen by as many potential editors and referees as possible; and only then they will finally submit it to a journal. Others with the option of writing a paper with the two-year follow-up results will wait for the, say, 5-year follow-up before submitting the paper to a journal. There are good reasons for these – incentives dictate these strategies – but years pass before we have any credible, peer-reviewed publications on some experiments. That cannot be good for our policymaker counterparts and colleagues. I wish that we had more of the types of nimble experiments (using administrative data and quick follow-ups) of the kind the Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund (SIEF) at the World Bank funds, which would also reward quick publications and dissemination.

Even more reason to repeat “don’t sit on your paper.” Now, if you’ll excuse me, I need to go and heed my own advice…

Join the Conversation