Teachers are important. From

Pakistan to

Uganda to

Ecuador to the

United States, study after study shows that a good teacher can make a big difference in student learning. If we want more student learning, then it seems that “hire better teachers” or “make sure you retain the good teachers,” would be good bets. But identifying good teachers is challenging. The studies above measure the learning gains associated with being in a particular teacher’s class, but they don’t identify observable characteristics of good teachers, like “tall teachers are good teachers” or “brunette teachers are good teachers.” While those characteristics seem silly, some areas that seem like no-brainers – such as teacher education and experience – are

not consistently correlated with student learning.

Many countries want to do a better job of identifying the best teachers (to retain and reward them) and the worst teachers (to help them and – in some cases – dismiss them). Some countries have begun to test teachers. The World Bank’s Service Delivery Indicators initiative has tested teachers’ pedagogical ability and basic math and reading ability in several countries, to largely dispiriting results.

A new study by Cruz-Aguayo, Ibarrarán, and Schady asks the question, " Do tests applied to teachers predict their effectiveness? " Short answer: In Ecuador, no.

How do we know? In Ecuador, one in three public school teachers work on a short-term contract. Tenured teachers have higher pay and more benefits. Each year, new tenured slots open and candidates apply for them. Candidates with the highest score on an evaluation get the tenured jobs. The evaluation has three elements, each receiving equal weight: a test, a demonstration class, and points awarded for experience, degrees, or in-service professional development.

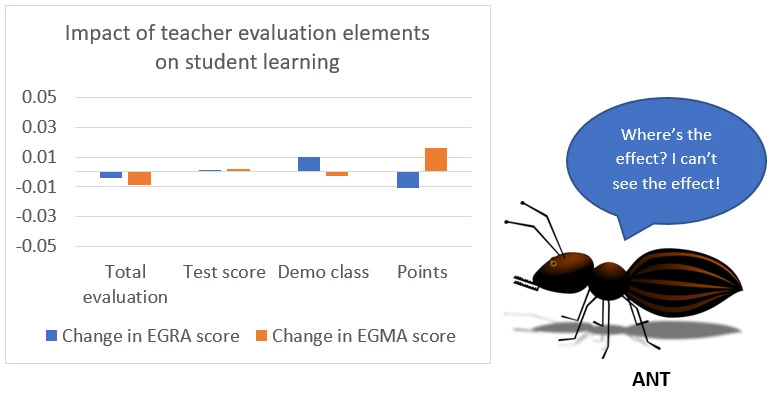

The authors then look at schools with at least two contract teachers who participated in the evaluation. They compare children within that school to see if teacher performance in the evaluation has any impact on student learning. For all children, they control for child age and class size. In additional specifications, they control for parental education and household socioeconomic status; they only have that information for three-quarters of the sample. It doesn’t affect the results.

Student learning is measured in six different ways. They use the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) at mid-year (#1) and at the end of the year (#2), the Early Grade Math Assessment (EGMA) at mid-year (#3) and at the end of the year (#4), and the change in EGRA (#5) and EGMA (#6) scores.

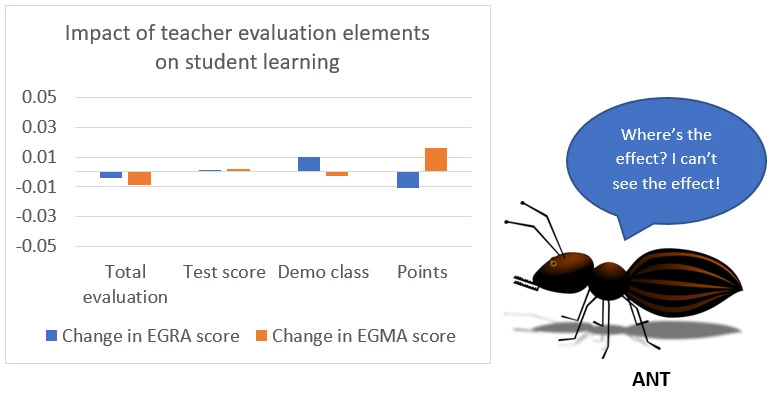

Because children aren’t randomly assigned to classes, they regress teacher evaluation results on student characteristics. That shows if certain kinds of students (for example, rich students or boys) get assigned to the best teachers. There’s no evidence of selective sorting. So after all that, what’s the result? According to the authors, there is “no evidence that the test score or any of its components, the score on the demonstration class, points on the Méritos scale, or the aggregate score on the Concurso predict child achievement in language or math.” Across 84 coefficients [6 outcomes x (6 evaluation elements + 1 total score) x 2 specifications], not a single one is statistically significant.

These are precise zeros: “In the specifications with the additional controls, we can rule out positive associations between the total Concurso score and child test scores larger than 0.02 standard deviations for language, and 0.03 standard deviations for math.”

How does this fit with other results on tests?

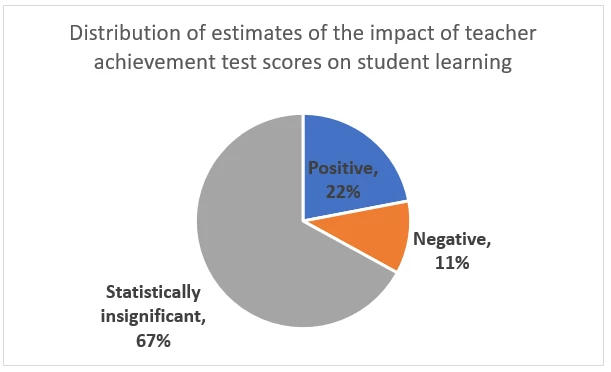

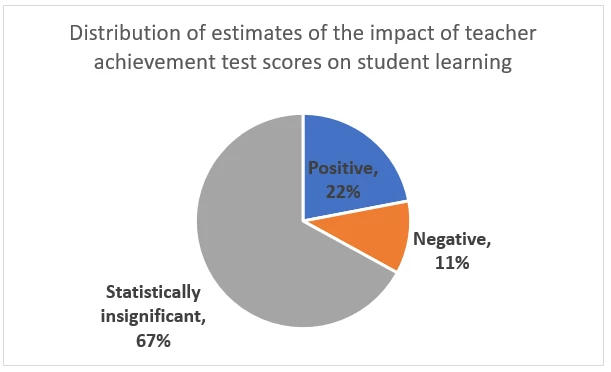

Hanushek and Rivkin brought together the evidence some years ago. Out of 9 estimates, 6 were statistically insignificant, 2 were positive, and 1 was negative. (As the figure below shows, most of THAT pie is an insignificant, unappetizing gray.) So this Ecuador data falls in line with much of the existing evidence.

That said, evidence from Peru compares students taught by the same teacher in at two subjects to see whether the students perform better in the subject where the teacher herself tests better. They do, sometimes: “one standard deviation in subject-specific teacher achievement increases student achievement by about 9% of a standard deviation in math. Effects in reading are significantly smaller and mostly not significantly different from zero.”

Beyond tests, a study of demonstration lessons on subsequent teacher performance in Argentina – by Ganimian, Ho, and Alfonso – found modest predictive power of demonstration lessons in identifying candidates who would go on to perform particularly poorly, but not so much for identifying future top performers.

Does this mean that teacher tests are worthless? No.

When a test of teachers in Mozambique shows that zero percent of teachers have a minimum standard of language knowledge to teach their subject, or a test in Nigeria shows that less than 60 percent of teachers can subtract double digits – as found by Bold and others – an adverse impact on student learning seems likely. It would be interesting to know – in the Ecuador context studied by Cruz-Aguayo, Ibarrán, and Schady – whether any teachers are below a minimum level of knowledge. It’s possible that all the contract teachers who are participating in the evaluation have some basic level of content knowledge. Without minimal content knowledge, teaching the content would seem impossible.

That said, these results from Ecuador are an important reminder that a teacher test is no magic bullet – and may be completely useless – in identifying great candidates for teachers. Ultimately, there may be no shortcut for identifying great teachers: The best bet may be to hire as best as one can, but then rigorously evaluate the teachers’ value added to student learning over several years before granting permanent status.

Bonus materials

Here are open-access versions to three of the papers linked above that have been published in journals

Many countries want to do a better job of identifying the best teachers (to retain and reward them) and the worst teachers (to help them and – in some cases – dismiss them). Some countries have begun to test teachers. The World Bank’s Service Delivery Indicators initiative has tested teachers’ pedagogical ability and basic math and reading ability in several countries, to largely dispiriting results.

A new study by Cruz-Aguayo, Ibarrarán, and Schady asks the question, " Do tests applied to teachers predict their effectiveness? " Short answer: In Ecuador, no.

How do we know? In Ecuador, one in three public school teachers work on a short-term contract. Tenured teachers have higher pay and more benefits. Each year, new tenured slots open and candidates apply for them. Candidates with the highest score on an evaluation get the tenured jobs. The evaluation has three elements, each receiving equal weight: a test, a demonstration class, and points awarded for experience, degrees, or in-service professional development.

The authors then look at schools with at least two contract teachers who participated in the evaluation. They compare children within that school to see if teacher performance in the evaluation has any impact on student learning. For all children, they control for child age and class size. In additional specifications, they control for parental education and household socioeconomic status; they only have that information for three-quarters of the sample. It doesn’t affect the results.

Student learning is measured in six different ways. They use the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) at mid-year (#1) and at the end of the year (#2), the Early Grade Math Assessment (EGMA) at mid-year (#3) and at the end of the year (#4), and the change in EGRA (#5) and EGMA (#6) scores.

Because children aren’t randomly assigned to classes, they regress teacher evaluation results on student characteristics. That shows if certain kinds of students (for example, rich students or boys) get assigned to the best teachers. There’s no evidence of selective sorting. So after all that, what’s the result? According to the authors, there is “no evidence that the test score or any of its components, the score on the demonstration class, points on the Méritos scale, or the aggregate score on the Concurso predict child achievement in language or math.” Across 84 coefficients [6 outcomes x (6 evaluation elements + 1 total score) x 2 specifications], not a single one is statistically significant.

These are precise zeros: “In the specifications with the additional controls, we can rule out positive associations between the total Concurso score and child test scores larger than 0.02 standard deviations for language, and 0.03 standard deviations for math.”

How does this fit with other results on tests?

Hanushek and Rivkin brought together the evidence some years ago. Out of 9 estimates, 6 were statistically insignificant, 2 were positive, and 1 was negative. (As the figure below shows, most of THAT pie is an insignificant, unappetizing gray.) So this Ecuador data falls in line with much of the existing evidence.

That said, evidence from Peru compares students taught by the same teacher in at two subjects to see whether the students perform better in the subject where the teacher herself tests better. They do, sometimes: “one standard deviation in subject-specific teacher achievement increases student achievement by about 9% of a standard deviation in math. Effects in reading are significantly smaller and mostly not significantly different from zero.”

Beyond tests, a study of demonstration lessons on subsequent teacher performance in Argentina – by Ganimian, Ho, and Alfonso – found modest predictive power of demonstration lessons in identifying candidates who would go on to perform particularly poorly, but not so much for identifying future top performers.

Does this mean that teacher tests are worthless? No.

When a test of teachers in Mozambique shows that zero percent of teachers have a minimum standard of language knowledge to teach their subject, or a test in Nigeria shows that less than 60 percent of teachers can subtract double digits – as found by Bold and others – an adverse impact on student learning seems likely. It would be interesting to know – in the Ecuador context studied by Cruz-Aguayo, Ibarrán, and Schady – whether any teachers are below a minimum level of knowledge. It’s possible that all the contract teachers who are participating in the evaluation have some basic level of content knowledge. Without minimal content knowledge, teaching the content would seem impossible.

That said, these results from Ecuador are an important reminder that a teacher test is no magic bullet – and may be completely useless – in identifying great candidates for teachers. Ultimately, there may be no shortcut for identifying great teachers: The best bet may be to hire as best as one can, but then rigorously evaluate the teachers’ value added to student learning over several years before granting permanent status.

Bonus materials

Here are open-access versions to three of the papers linked above that have been published in journals

- Do tests applied to teachers predict their effectiveness?

- Teacher quality and learning outcomes in kindergarten (showing teacher value-added in Ecuador)

- The impact of teacher subject knowledge on student achievement: Evidence from within-teacher within-student variation (showing the impact of teacher subject knowledge in Peru)

Join the Conversation