International mobility of people is measured much less accurately than that of goods or finances. The most common sources of global data are from national censuses, which occur only every 10 years (and take years more to come out). Specialized surveys in some countries allow more frequent measurement of some flows, but such data are still relatively rare, and poorly suited to studying short-term migration movements.

A new paper by Bogdan State, Ingmar Weber and Emilio Zagheni offers an intriguing new approach to measuring flows of people across borders and perhaps a glimpse into what the future may bring. Their basic insight is that “Easily-obtainable geolocation data resulting from repeated logins to the same website offer the possibility of observing long-term patterns of mobility for a large number of individuals”.

They use data on the geographic locations of where over 100 million anonymized users log into Yahoo! services over a one-year period to build a database of global mobility patterns. On average, a user in their sample logged in more than 100 times over the year. Out of all anonymized users, 96.68% spent (tracked) time in only one country, 3.10% spent time in two countries, 0.20% in three countries, and 0.03% spent time in four countries or more.

They then define as a migrant anyone who spends at least 90 days in two countries during the year, and tourists as those who spent less than one month in another country. They also match to user-reported country of residence in the Yahoo! user database to identify home country, and end up with a sample of 223,344 migrants, and a sample of millions of tourists.

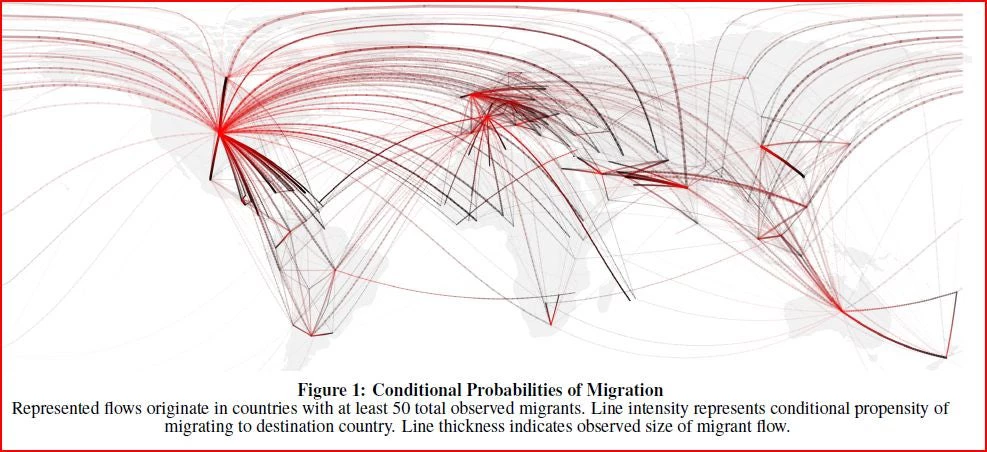

Using this information, they construct global mobility maps, such as the one below. Red indicates a mostly immigrant flow, black a mostly emigrant flow. The United States dominates among global migration destinations, as it is the top destination for 58 (44%) out of the 132 countries with at least 50 migrants represented in the dataset. The United States is followed by Great Britain and France, which represent the top migration destinations for 10 and, respectively, 20 countries in their sample.

When looking at both migrant and tourist flows, they note that “The most striking pattern is a web connecting all countries to the United States, followed by a smaller, though still noticeable tendency for many countries to be strongly connected with their former colonial metropolises - France, Spain and England, a trend from which Portugal however seems to be excepted. Another trend is the emergence of regional hubs. India, China, Australia, Brazil and Argentina, as well as South Africa are emerging as both migration and tourist destinations.”

They then merge this data with macro data on GDP, colonial ties, distance, etc. to estimate regressions at the country-pair level of the correlates of international movement. They find a strong association with colonial ties with individuals being close to 4 times as likely to migrate to a country to which their country of origin has a colonial tie (although this is weaker in the Commonwealth; A travel visa requirement lowers the odds of migration and tourism by an amount equivalent to losing a Commonwealth tie; having a common language increases the odds of migration and especially of tourism.

They note “The United States is the most “surprising” migration destination, in light of the explanatory variables included in the model. In context, the result is not counter-intuitive: the United States is known to be a popular migration destination for most countries, even though it imposes wide-spread visa restrictions, has few colonial ties, and is separated from most of the world’s countries by a considerable distance.”

Discussion

This is an interesting paper, pulling together a very large dataset on migration and tourism flows. As the authors note, several advantages are that they can measure migration flows in a consistent way globally, whereas typically countries use different definitions of what a migrant is; they can do this at high frequency; and they can examine a continuum of mobility definitions, including very short-term movements.

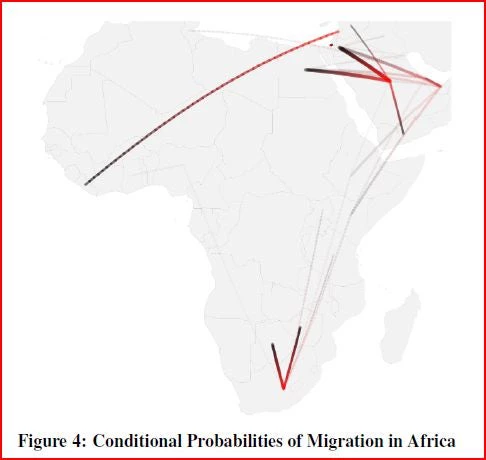

Obviously the most important limitation of the work is that Yahoo! users is a selected sample. The authors note that despite this concern, the regression analysis they conduct give results consistent with key findings in the sociological literature, and conditional probabilities of migration that are consistent with census data. The limitation seems more severe for migration between developing countries – in particular, they have very few users in Africa, leading to this rather sparse picture of intra-African migration

However, as certain technologies become more widespread, this basic idea suggests the scope for a lot of interesting data on movement. For example, Joshua Blumenstock has used this idea to look at internal mobility within Rwanda based on mobile phone location records. Eventually maybe we can just track all migration through Google Glasses location sensoring…

(h/t Steve Stillman and Jacques Poot for drawing my attention to this paper).

Join the Conversation