Measuring the sales, costs, and profits of small firms is notoriously difficult. One of my most cited papers focuses on measuring profits, and says a reasonable result can be obtained through a simple single question – which is welcome news for many researchers battling survey length, but runs into trouble at times when firms won’t give an answer. That paper has much less to say on the optimal way of measuring revenues or costs, and I often get questions from people asking for recommendations as to best practice.

I now have a new answer. A recent working paper by Stephen Anderson, Christy Lazicky, and Bilal Zia sets out a new approach to measuring firm outcomes that combines automatic consistency checks of electronic data collection with triangulation and dynamic adjustment. I’ll explain their approach, discuss its benefits, and some caveats.

Their approach

- Triangulating Sales

They start with a Money In section, which asks three separate measures for monthly business sales:

- Monthly recall: recall their total sales or all the money collected into the business during the last month

- Estimate based on weekly recall: the respondent is asked for the best week and worst week of sales in the past month – the software then averages and multiplies by 4.25.

- Estimate based on daily recall: the respondent is asked for last day’s sales, best day’s sales, and worst day’s sales in the last month – the three are then displayed together as anchors, with the respondent then asked for sales on a typical day. This is then multiplied by number of days per week the business transacts with customers, and then by 4.25 weeks per month.

Then the owner is shown all three estimates, and asked to give their “best estimate” of sales for the past month (see figure 1 for an example below). This is done first before any discussion of costs and profits, and then there is a chance to adjust this again later after completing the costs and profits sections.

Figure 1: Example of Sales Triangulation

1. 2. Measuring costs

The authors have a money out section which gets owners to systematically build estimates for 13 major cost categories, which the authors view as high-level mental accounts. Examples include raw materials, location, loan servicing, energy, transport, equipment, etc. For each of these high-level categories, there are sub-questions that then focus on amount and frequency of these costs, which are then aggregated back up to monthly levels. At the end of this, the owner is presented with a visual of the total costs in each category, and total monthly cost, and given the opportunity to revise and adjust until they are happy with the final total.

3. Measuring profits

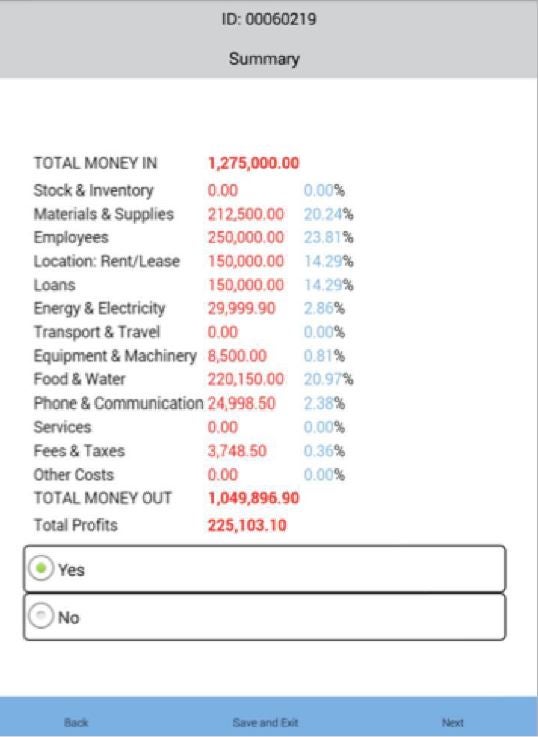

Owners are first asked after the sales question to recall “total profits or the money leftover in the business after paying for all bills, expenses, and salaries during the last month”. Then a second estimate is calculated by the software as money leftover, as sales minus costs. This is presented to the owner in the form of a basic income statement, showing the money they say they received in, the amount they said they spent in the 13 cost categories, and the difference (see Figure 2). They then can use these anchors to decide whether further adjustments of their sales estimate or cost estimates are needed, and finally arrive at their best estimate of profits.

Figure 2: Example of Profits Calculation

Time taken

This definitely takes more time than simply asking for last month’s sales and last month’s profits. The authors note it takes an average of 20 minutes for their money in section, 30 minutes for their money out section, and an additional 10 minutes for adjustments. So an hour to get this information. However, they note that just implementing the sales (money in) module, and then asking profits directly after this seems to do reasonably well, and so can serve as a “light” version of the instrument. Bilal Zia provides their questionnaires, survey CTO modules, and enumerator training instructions for both the regular and light versions on his website.

How much of an improvement does this make?

The challenge in trying to come up with a new measurement tool in cases like this is the lack of a gold standard – we don’t know what the true sales and profits of firms are, so if we use different methods and find out that they give different answers, how do we know whether we are making things better or worse?

The paper uses their field tests of this instrument in Ghana, Rwanda, and Uganda, and does a couple of things to try to convince the reader that this new method offers an improvement on just asking directly:

- Does the method appear to reduce noise? The authors look to see whether their approach yields lower cross-sectional coefficients of variation, and higher autocorrelations for profits and sales. They do so by comparing the initial estimate of sales to the triangulated version, and an unaided assessment of profits to their final best estimate.

- For sales, they find the triangulated levels of sales tend to be 10-25% higher than the simple estimate, the C.V. falls by 4 to 15% (e.g. from 1.08 to 0.92), and the sales are slightly more autocorrelated (e.g. an autocorrelation of 0.55 increases to 0.59).

- For profits, the comparison is trickier, since they note their first estimate of profit already comes after asking lots of detailed anchoring questions on sales. The C.V.s are actually slightly smaller for their direct estimate of profits than for the calculated final version. But in a small sample of 59 firms in which they ask directly about profits first, their calculated measure has a slightly lower C.V. (0.64 vs 0.68).

- Does the method yield estimates more consistent with those of independent verifiers: They compare their estimates to those of bank loan officers in Ghana and business coach assessments in Uganda. They find that, overall, their measures more closely approximate those of these independent assessments.

While these improvements in C.V. and autocorrelation may not seem that large in magnitude to you, they actually can make a big difference in the effective sample size you need for detecting a given effect size. For example, with one baseline and one follow-up, using Ancova, to detect a 20% increase in sales with 80% power, you need a sample size of 640 firms when the C.V. is 1.08 and autocorrelation is 0.55 – and this falls to only 428 firms when the C.V. is 0.92 and the autocorrelation is 0.59. So this has the potential to reduce the sample size you need by almost 50%!!!

Caveats

I think this triangulation approach looks very promising in small firms, but do worry about the amount of time it takes when I often already have survey instruments pushing up against the limits of firms being willing to respond. In employing this, I would bear the following caveats in mind:

- Potential impact on attrition: lengthening the amount of time taken to do the survey and asking a lot of what seem rather repetitive questions about business financials might make firms less willing to answer in future rounds – or conversely they might find value from getting a better handle on their finances and so be more willing to respond. However, Bilal and Steve have successfully used the method in several studies with reasonably low attrition, and the light version isn’t nearly so long.

- Preventing crazy outliers vs distributional shifts: my initial reaction was that I thought this triangulation approach would be particularly good at dealing with large outliers that come from mismeasurement, and that add a lot of noise to our estimation. But while their paper doesn’t directly consider the prevalence of outliers, it seems from kernel density figures that there are shifts in levels for much of the distribution, not just correcting of the tails. This does mean it is doing something different from what you could just accomplish by truncating outliers.

- Cash vs Accrual Basis: the framing here is very much on a cash accounting basis – asking about money in, money out, and what’s left. This generally makes sense for sales (although it then potentially misses sales made on credit until these accounts receivables are paid). It is more of an issue for profits for two reasons. The first is what it doesn’t capture (value of owner’s time, depreciation of capital, etc.), which is also common to the direct measure. The second is an issue with transaction timing. This is something we discuss in sausage paper on profits – that there is often a mismatch in timing between when expenses take place versus when the revenues from those expenses are realized. This mismatch is not much of an issue for daily fruit and vegetable sellers, and much more of an issue for manufacturing, construction, and vendors of durable goods. The enumerator instructions apparently try to get the owner to consider this when asking about costs, but I think the direct measure can be appealing for this reason. Their light approach might be doubly appealing as a result – it isn’t as time intensive, and it doesn’t require worrying so much about timing mismatches. Moreover, these tools can of course be modified – if you are working with firms where these other issues are more prevalent, the questions can be modified to try to capture them more easily.

Join the Conversation