A decade ago, I was part of a team that ran an unusual proof-of-concept experiment with Indian textile firms (paper, ungated). We hired a multinational consulting firm with a small sample of 17 firms, and had them conduct intensive one-on-one consulting to treatment plants at (an academically discounted) cost of $75,000 per plant. This led to large improvements in management, and improvements in quality and productivity. But the sample was small and relatively homogeneous, and the intervention was expensive and done under substantial researcher oversight. So when several governments expressed interest in improving management in their own countries, the key questions were whether this result could be replicated at a larger scale, and whether there were more cost-effective ways to deliver these benefits.

In a new working paper, Leonardo Iacovone, Bill Maloney and I report on our efforts to answer these questions through an experiment in Colombia. Data from the World Management Survey show that the average level of management practices in Colombia is similar to that of poorer countries like Kenya and India, and substantially below that of more developed economies. The Government of Colombia asked us to work with them in testing if management could be improved in their auto parts sector, which had similar management practices to the manufacturing sector as a whole in their country.

The Sample and Intervention

The government launched a call in 2012, and 159 firms were selected for the program. This is an order of magnitude larger than the sample size of the Indian experiment. Operating at this larger scale meant the firms were a lot more heterogeneous in both product and size. They produced a wide range of products as second-tier suppliers to large car manufacturers, making metal and plastic parts, fenders, tires, paints, glass, etc. They ranged in size from 10 to 310 workers, with an average of 59 workers, and almost all were single plant firms.

The government contracted the National Productivity Center (Centro Nacional de Productividad, or CNP) to implement the program. They are an experienced Colombian non-profit institution who use local consultants experienced with working with Colombian firms.

These 159 firms were divided into three groups of 53 firms each, and randomly allocated to three groups:

1. Control group: as in India, all firms started with a management practices diagnostic. Here, this took a team of 6 consultants two weeks to assess the firm’s management practice in five broad areas: logistics, human resources, marketing and sales, finance, and production. At the end of the diagnostic, the firm received a report that recommended areas for improvement.

2. Individual treatment group: after the diagnostic, the firm received 500 hours of one-on-one individual consulting spread over six months to help the firm improve in these five areas of management. This was similar in intensity to the individual consulting done in India, but cost $29,000 per firm due to using local consultants rather than a multinational consulting firm.

3. Group treatment: after the diagnostic, the firms in this treatment were allocated to groups of 3 to 8 firms, formed according to geographic area. Crucially the heterogeneity in the industry meant that firms were not forming groups with their competitors, but instead a firm making car windows might be in a group with a firm making rubber floor mats and another firm making metal parts. Firms would then send the staff in charge of a particular production area to a central location (e.g. a hotel conference room), and the consultant in charge of that area would work with the group together. The idea is that this would lower the cost of implementation, and potentially leverage group learning dynamics. Firms received 408 hours of consulting at a cost of $10,500 per firm, or approximately one-third the cost of the individual intervention.

Challenges for impact evaluation

As is common in moving from researcher-led interventions to larger scale government-run programs, a number of challenges for impact evaluation arose:

· When you don’t control the budget, you don’t control the project: In the India case, the research team raised the funding and directly hired the consulting firm, who then would implement everything requested by the research team on our timeframe. But here, CNP was contracted by different government agencies for different parts of the project. This affected the project in a couple of important ways: first, a different agency was paying for the group treatment than the individual treatment, and due to a delay in their budget, this resulted in the group intervention getting implemented nearly a year after the individual intervention, rather than at the same time as we had planned. Secondly, data collection was also being paid for by the government, with multiple delays and gaps while waiting for new contracts to get issued.

· Collecting key performance indicators consistently and reliably from SMEs is hard: firms applied to the project in 2012, did the diagnostic in 2013, the individual intervention occurred in 2014, the group intervention in 2015, and we tried to collect data through to the end of 2017. This was a lot of time to be trying to get data from the firms, and we struggled to get a lot of the firm data we wanted, continually paring back the set of variables we asked for. As a consequence of poor management, firms did not always keep records on many indicators we would have liked. Because the firms were multi-product and heterogeneous, measuring output over time was challenging. E.g. a firm might report output of 10,000 metal parts in January, then change to recording output in different units in February, then switch to reporting in pesos the next year. Firms were also reluctant to share financial information. Moreover, some firms just got sick of reporting and refused after a while.

As a consequence, the things we can measure best are management practices, which were measured during the diagnostic and follow-up rounds; and employment, which we can track (through to the end of 2018, 3-4 years post-intervention) by matching firms to administrative records from the PILA (Colombia’s social security and health benefits system). We supplement this with analysis of the firm data, which is noisier and suffers from higher attrition.

What works best to improve management?

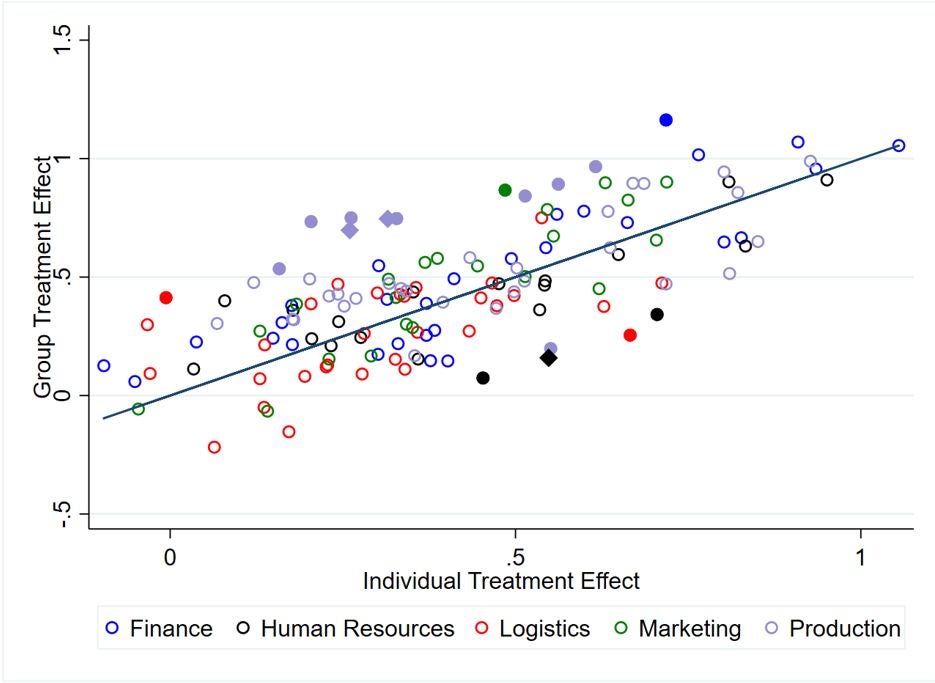

Management practices were measured in terms of 141 individual practices, developed by CNP, classified into five areas: financial practices (made up of 29 individual practices), human resource practices (20), logistics practices (31), marketing practices (22), and production practices (39). Each was measured on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (not used) to 5 (fully implemented and under control). We find that both treatments led to similar improvements in the level of management practices, with an 8 to 10 percentage point improvement compared to the control group. Moreover, not only did the two different approaches to improving management result in a similar aggregate improvement in management, but also to a similar mix of practices improved. Figure 1 below shows the results of 141 treatment regressions (one for each practice), and we see the correlation is strongly positive (0.71), so that the practices which improved the most under one treatment tended to also improve the most under the other.

Figure 1: Both the individual and group approaches led to similar improvements in management practices

Note: filled in markers denote practices where we can reject equality of treatment effects between the individual and group treatments.

What did this improvement in management do for firms?

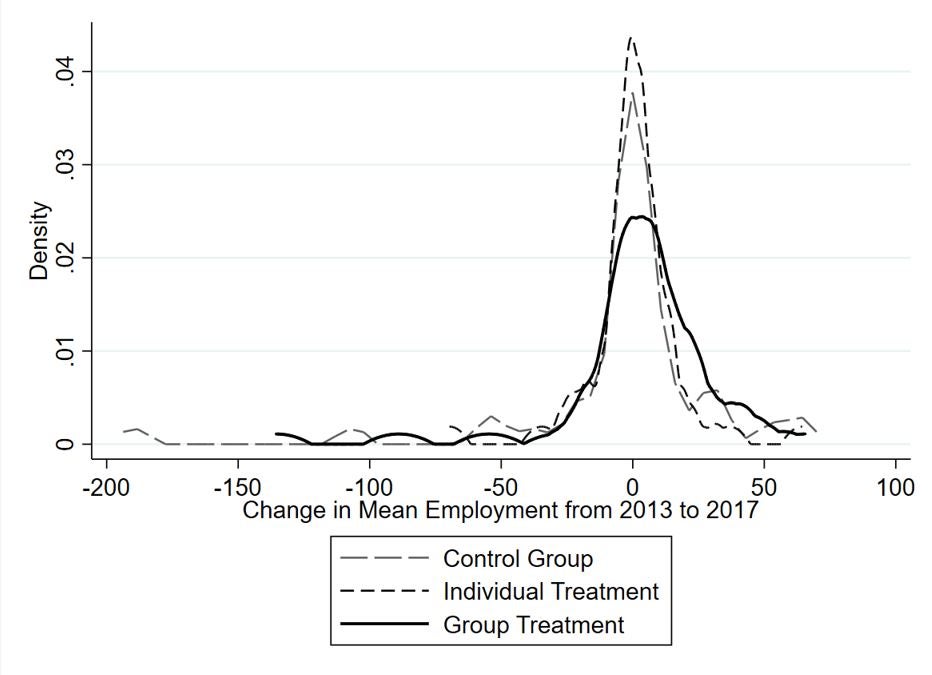

As noted above, paid formal employment is the best measure we have of growth in firm size, and is a key measure that policymakers are also interested in. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the change in mean employment from 2013 to 2017 in each of our three groups. Two key features are apparent. First, the control group and individual treatments have similar distributions of changes in employment, while the group treatment has more firms with positive employment increases. But, second, there is a long left tail that comes from a handful of firms closing down and therefore experiencing a large reduction in employment. We estimate the group treatment increased employment by a statistically significant 6 to 7 workers if we condition on remaining in operation, and by 4 workers (with larger standard errors) when including these large drops for the few firms that closed. The quantile treatment effects on employment are positive and significant in the 60th and 70th percentile range for the group treatment. So there is some evidence that the group treatment increased firm size, whereas this is not the case for the individual treatment.

Figure 2: Distribution of Changes in Employment 2013-2017 by treatment status

The other data we have is also consistent with the group treatment making firms larger – they have more sales (p=0.12), and use more energy, suggesting they are producing more. In contrast, the impacts of the individual treatment are always smaller, although we can only sometimes reject equality of the two treatments.

One of the cool things we are able to do with the anonymized administrative data on employment is to see whether workers move across firms in the study. This helps answer questions like “did the group treated firms steal away workers from the control or individual groups?”. The answer is no – there is a lot of worker churn – firms typically have 3 percent of workers leave each month and 3 percent join, but only 32 of the 23,156 distinct workers we track worked for firms in more than one treatment group.

So should more government firm support programs be working with small groups?

The group treatment was able to deliver the same improvement in management as the individual treatment at one-third the cost. While we struggle to measure profits over time, using estimates based off our sales data and baseline profit-to-sale ratios suggest that it is likely the group treatment paid for itself in 14 months. So this is encouraging, even given the measurement issues noted above and fact that it is one example from one country. I also note that a typical question I often get presenting firm experiments is “if this is so good, why didn’t firms buy it themselves?” – here such a group treatment is not available on the market, and there does seem a role for policy at least in overcoming these coordination issues. (Of course, there are also many other market failures that can justify government support for improving management). I therefore think there is enough here to encourage more experimentation with this group model – especially given other recent studies that suggest a role for group learning amongst smaller firms. So just as Colombia was prepared to learn from the Indian experiment and build on it, I hope other countries planning management improvement efforts can build on this Colombian effort.

Join the Conversation