This post is coauthored with Jorge Cuartas

We recently led a session on designing, implementing, and evaluating parenting programs in fragile, conflict, and violence affected (FCV) settings for a group of World Bank Early Learning Partnership (ELP) grantees. As the number of ongoing, mostly civil conflicts throughout the world steadily rises each year, operating in these settings is likely to become normative in the near future. Below we will summarize the discussions that took place during the session as well as the most important takeaways.

During the first part of the session, we discussed the theoretical framework of parenting programs and some special factors that should be considered when these programs are implemented in FCV settings. Scientific findings in the biology and psychology of human development have demonstrated that the first years of life are a crucial and sensitive period of brain and skill development. During these early years, both positive (e.g., nurture, encouragement, secure attachment) and adverse (e.g., extreme poverty, violence, other psychosocial stressors) experiences can have a profound impact on an individual’s well-being. Unfortunately, the same difficulties that impact a child’s development also affect its caregivers’ (e.g., parents) mental health and behaviors, leaving the child even more vulnerable. These threats are particularly salient in FCV settings, where violence, displacement, and other psychosocial stressors impose heavy tolls on both caregivers’ and children’ wellbeing.

The literature has increasingly recognized parenting programs as a promising approach to support both adult caregivers and children facing adversity. Existing studies on parenting interventions focus strongly on behavior and are grounded in social learning theory. Generally, these interventions also seek to reduce harsh parenting and foster positive parent–child interactions to create an adequate environment for children's cognitive, social, and emotional development.

Overall, evidence-based parenting programs share the following core components: 1) content that teaches parents and caregivers to understand their children’s needs and behaviors; 2) skills to self-regulate, problem-solve, and improve parent-child relationships; 3) an emphasis on the importance of child-led play; and 4) non-violent approaches to discipline instead of physical punishment and psychological aggression. These programs also have the following set of delivery methods in common: 1) demonstration and modeling, 2) practice and rehearsal of behaviors, 3) role-playing, 4) positive feedback from program facilitators, 5) homework, and 6) parental goal setting.

Although evidence-based parenting programs have similar content and delivery approaches, studies show that families in FCV settings require additional support. First, conflict, violence, displacement, and threat all have an immense impact on caregivers’ stress and behaviors. Apart from some notable exceptions, however, parenting interventions for families living in extreme adversity have paid little substantive attention to parents' psychosocial well-being and mental health. Second, little evidence exists on whether remote supports such as SMS messages or chatbots are even useful as complements or substitutes when in-person support is not feasible due to conflict and/or displacement.

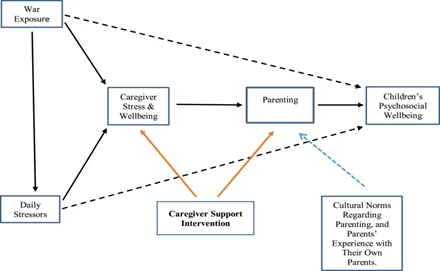

In response to evidence that parental stress mediates negative effects on children’s well-being as well as to the lack of evidence on parenting programs that focus on addressing caregiver well-being, Miller et al. (2020) developed a conceptual model for a parenting program that can be implemented in FCV settings (see Figure 1). This model relies on a theory of change that presupposes that lower stress levels and improved psychosocial well-being enable parents to make better use of the knowledge and skills that they already possess and to acquire new skills through training. Improved parenting, in turn, improves children’s psychosocial and emotional development.

Figure 1. Miller et al.’s (2020) Conceptual Model of Parenting Programs in FCV Settings

During the second part of our session with the ELP grantees, we discussed the results of two parenting programs implemented and evaluated in FCV settings: Semillas de Apego in Colombia and a remote adaptation of Reach Up and Learn (RUL) in Syria and Jordan.

Semillas de Apego is a parenting program founded on a community-based psychosocial model for caregivers of young children affected by conflict and forced displacement. The program aimed to create awareness of and provide tools to address the negative effects that conflict and displacement have on caregiver psychological well-being, child well-being, and the quality of the child-caregiver relationship.

The program consisted of 15 caregiver group sessions, delivered once per week. Each session lasted approximately 2.5 hours. Each group included 12-16 participants, all of who were primary caregivers of at least one child aged 0–5 years. The group sessions were based on a multi-theory framework that included attachment theory, trauma informed models, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Community facilitators with no formal training in psychology or social work led the meetings, which is an important element of the intervention because highly qualified professionals are often scarce in FCV contexts.

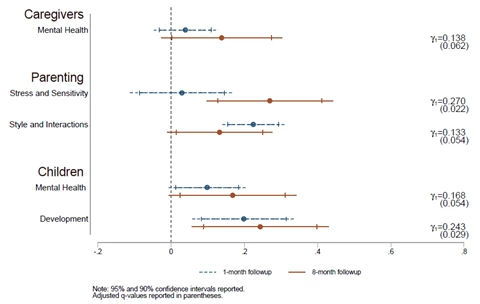

Moya et al. (2021) [1] summarized the results of the experimental evaluation of a pilot of Semillas de Apego (See Figure 2). One month after the intervention finished, the authors found short-term improvements in the participants’ parenting style, interactions with their children, and children’s mental health and development. Eight months after the program ended, not only were the effects sustained, but the authors also observed that the program had positive effects on parental stress and sensitivity and on caregivers’ mental health.

What challenges occurred within the context of Moya et al.’s (2021) study? The presence of “invisible borders” prevents sessions with caregivers from different neighborhoods. In this sense, the random assignment for the evaluation should be carried out at the childcare center at the expense of statistical power and inference. Moreover, active conflicts can hinder or prevent researchers from following up with the participants, which consequently limits the amount of data on home interactions that they can collect.

Figure 2. The Short- and Medium-term Effects of Semillas de Apego (Moya et al., 2021)

Another example that we discussed was the Reach Up and Learn (RUL) program, which was adapted for remote delivery to Syrian and Jordanian families. The program was delivered via telephone. Local community health volunteers called each caregiver 18 times over a six-month period (3 calls per month). RUL aimed to encourage caregivers to engage in activities that supported their children; help caregivers listen, understand, respond to, and praise their children; enable caregivers to use more positive discipline practices; and improve caregiver well-being.

After RUL ended, Global TIES for Children at New York University evaluated the effectiveness of remote delivery. The authors divided participant households into two groups: the comparison group received phone calls focused on health and nutrition, each of which lasted an average of 23 minutes. The treatment group received the same health and nutrition-based phone calls as the control group, as well as an early childhood development and caregiver well-being check-in phone call, which lasted 7 minutes. This evaluation found that the program had no effects on improved caregiving or child development outcomes. Yet, the authors did find positive effects on caregivers’ depression.

The evaluation team discussed two important intervention features that might explain the lack of effects on caregiving and child development. First, the short duration of the phone calls might have had little impact. The ECD content was limited to roughly 7-10 minutes per call. In comparison, other in-person versions of RUL included between 3,000 (1-year program) and 6,000 minutes (2-year program) of intervention content. Second, the adapted version of RUL excluded some relevant components of the in-person version such as demonstration, practice, and feedback. The lack of effects suggests that it might be worthwhile to include alternative supplemental elements in parenting programs delivered remotely.

In upcoming blogs, we will share more evidence on adaptation of content and delivery-mode of parenting programs in non-FCV settings. Stay tuned!

[1] Moya, A., Sanchez-Ariza, J., Torres, MJ., Harker, A., Lieberman, A., Niño, B., Reyes, V. 2023. Maternal Mental Health and Early Childhood Development in Conflict-Affected Settings: Experimental Evidence from Colombia. Working Paper Universidad de los Andes.

Join the Conversation