This post is co-authored with Martina Björkman Nyqvist and Jakob Svensson

Poor quality plagues public service provision in many developing countries. For example, doctors in Tanzania completed less than 25% of the essential checklist for patients with malaria, a disease that is endemic in the country. Indian doctors asked an average of one question per patient (“What’s wrong with you?”). In Uganda, the average absence rate among primary school teachers was 27% and 37% among primary health center staff.

The widespread problem of poor public service delivery in developing countries has in the last decade led to increased attention to evaluate and experiment with different approaches to improve public services provision.

Power to the People

One suggested method to fight the poor performance public service delivery is inspired by the Community Driven Development (CDD) approach. It emphasizes participation by the communities served by public services. The approach seeks to enhance beneficiary involvement as a way of strengthening demand-responsiveness and local accountability. These CDD projects have become increasingly popular and the World Bank alone spent about 85 billion USD over the last decade on these types of projects. However, few of the experiences have been rigorously evaluated and the results of those impact evaluations have been mixed.

One rigorous evaluation of such project, however, took place in the primary health care sector in Uganda. The results of this randomized field experiment on community-based monitoring of public primary health care providers have been reported earlier by Martina and Jakob in “ Power to the People”. Localized nongovernmental organizations encouraged communities to be more involved with the state of health service provision by facilitating a set of meetings: (i) a community meeting – a two-day afternoon meeting with community members from the catchment area and from all spectra of society and with on average more than 150 participants per day and per community attending; (ii) a health facility meeting – a half-day event, usually held in the afternoon at the health facility, with all staff attending; and (iii) an interface meeting – a half-day event with representatives from the community and the staff attending. This part of the process focuses on participation.

In order to facilitate a participatory process in which the communities got engaged and focused their discussions on issues where health provider performance and quality of service delivery was low, they also provided the users with information – a report card – about the quality of care provided in their local facility as well as entitlements according to the government standard in comparison to the national and district averages. This element of the intervention emphasizes information.

The final outcome of the process was an action plan jointly agreed upon by the community and the health staff. The action plan outlines the community’s and the providers’ joint agreement on what needs be done to improve health care delivery, how, when, and by whom and how progress will be monitored.

A year into the intervention, treatment communities were more involved in monitoring the providers, and health workers appeared to exert higher effort to serve the community. This resulted in large increases in utilization and improved health outcomes: reduced child mortality and increased child weight.

Two questions

The paper, however, raised two questions: 1) are those results sustainable in the longer run, and 2) since the intervention combined a participatory process and the provision of information (which is costly to collect), what would the effect of a more standard participatory intervention be and how important is information in these types of programs?

In our recent working paper, “ Information is Power ” we address both questions. First, we did a long-term follow-up of the communities that participated in the initial experiment in Uganda. Between 2006 and 2009 (the long-term follow-up period), the local NGOs re-engaged for a total of four days with the communities based on their initial joint action plan (they did not, however, disseminate any new information, beyond the initial report card nor did they initiate any new processes). Four years after the initial intervention, we find significant longer run impacts of the intervention that combines participation & information. Health care delivery (increased utilization and improved adherence to clinical guidelines) and health outcomes (reduced child mortality and increased weight-for-age and height-for-age for children) improved in the treatment as compared to the control group. For example, the estimated rate-ratio for under-five mortality; i.e., the ratio of the incidence of child deaths in the treatment relative to the control group, implies a 23% reduced risk of under-five deaths in the treatment group.

Without information, there is no impact of the pure participatory intervention

Second, we aimed at disentangling how important information is in these types of participatory processes. In parallel with the long-run follow-up of the participation & information intervention, we initiated a second experiment testing a participation (only) intervention. We implemented the participatory component of the intervention described above (and evaluated in Power to the People), including the three facilitated meetings. But in that participatory experiment we did NOT disseminate any information about the health facility’s performance. No report cards were prepared and shared with the population. Thus, the community now had to build their reform agenda (action plan) on their perceived performance of the local health facility as opposed to the objectively measured performance of the health facility (which was provided to the participation & information intervention group through the information in the report cards).

The impacts of the interventions with and without information differ markedly. Without information, the process of stimulating participation and engagement (the participation intervention) had little impact on the health workers’ behavior, health outcomes or the quality of health care. It seems that information is an important component in community-based interventions.

Using data from the implementation phases of the two interventions, we investigate why the provision of information appears to have played such a key role. A core component of both experiments was the agreement of a joint action plan outlining the community’s and the providers’ agreement on what needs be done, and by whom, in order to improve health care delivery.

While the process of reaching an agreement looks similar on observable measures in the two treatment groups – the same number of community members participated in the community meetings and, on average, the two groups identified the same number of actions to be addressed – the type of issues to be addressed differed significantly.

In the participation group, the health provider and the community identified issues that primarily required third-party actions; e.g., more financial and in-kind support from upper-level authorities. While in the participation & information group, the participants focused to a much larger extent on problems that could be solved locally, and which either the health workers or the community themselves could address.

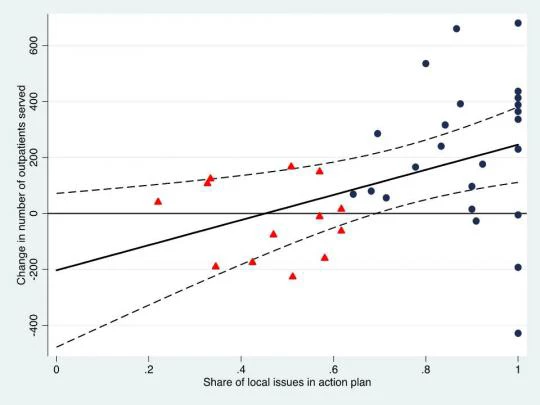

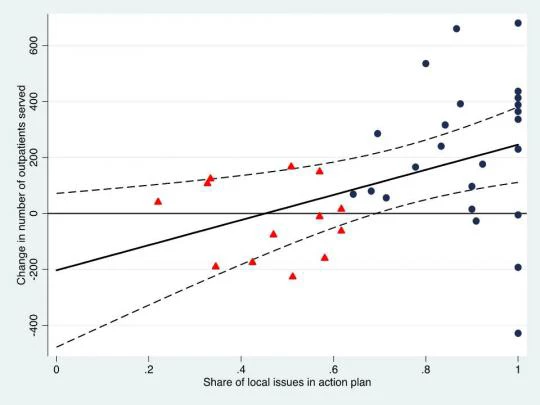

This is well illustrated in Figure 1. The share of local issues is higher in the participation & information group (blue dots) than in the participation group (red triangles). And the share of local issues correlates positively with the changes in the number of outpatients served by the health facility.

Figure 1: Outpatient care and the share of local issues in the joint action plan

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that lack of information on health facility performance makes it more difficult to identify and challenge (mis)behavior by the provider. That is, with access to information, users are better able to distinguish between the actions of health workers and factors beyond their control and, as a result, turn their focus to issues that they can manage and work on locally. Finally, when the community takes action in monitoring the providers, the health providers exert higher effort and utilization and health outcomes improve.

Martina Björkman Nyqvist is Assistant Professor at the Stockholm School of Economics.

Damien de Walque is Senior Economist in the Development Research Group at the World Bank.

Jakob Svensson is Professor at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.

Poor quality plagues public service provision in many developing countries. For example, doctors in Tanzania completed less than 25% of the essential checklist for patients with malaria, a disease that is endemic in the country. Indian doctors asked an average of one question per patient (“What’s wrong with you?”). In Uganda, the average absence rate among primary school teachers was 27% and 37% among primary health center staff.

The widespread problem of poor public service delivery in developing countries has in the last decade led to increased attention to evaluate and experiment with different approaches to improve public services provision.

Power to the People

One suggested method to fight the poor performance public service delivery is inspired by the Community Driven Development (CDD) approach. It emphasizes participation by the communities served by public services. The approach seeks to enhance beneficiary involvement as a way of strengthening demand-responsiveness and local accountability. These CDD projects have become increasingly popular and the World Bank alone spent about 85 billion USD over the last decade on these types of projects. However, few of the experiences have been rigorously evaluated and the results of those impact evaluations have been mixed.

One rigorous evaluation of such project, however, took place in the primary health care sector in Uganda. The results of this randomized field experiment on community-based monitoring of public primary health care providers have been reported earlier by Martina and Jakob in “ Power to the People”. Localized nongovernmental organizations encouraged communities to be more involved with the state of health service provision by facilitating a set of meetings: (i) a community meeting – a two-day afternoon meeting with community members from the catchment area and from all spectra of society and with on average more than 150 participants per day and per community attending; (ii) a health facility meeting – a half-day event, usually held in the afternoon at the health facility, with all staff attending; and (iii) an interface meeting – a half-day event with representatives from the community and the staff attending. This part of the process focuses on participation.

In order to facilitate a participatory process in which the communities got engaged and focused their discussions on issues where health provider performance and quality of service delivery was low, they also provided the users with information – a report card – about the quality of care provided in their local facility as well as entitlements according to the government standard in comparison to the national and district averages. This element of the intervention emphasizes information.

The final outcome of the process was an action plan jointly agreed upon by the community and the health staff. The action plan outlines the community’s and the providers’ joint agreement on what needs be done to improve health care delivery, how, when, and by whom and how progress will be monitored.

A year into the intervention, treatment communities were more involved in monitoring the providers, and health workers appeared to exert higher effort to serve the community. This resulted in large increases in utilization and improved health outcomes: reduced child mortality and increased child weight.

Two questions

The paper, however, raised two questions: 1) are those results sustainable in the longer run, and 2) since the intervention combined a participatory process and the provision of information (which is costly to collect), what would the effect of a more standard participatory intervention be and how important is information in these types of programs?

In our recent working paper, “ Information is Power ” we address both questions. First, we did a long-term follow-up of the communities that participated in the initial experiment in Uganda. Between 2006 and 2009 (the long-term follow-up period), the local NGOs re-engaged for a total of four days with the communities based on their initial joint action plan (they did not, however, disseminate any new information, beyond the initial report card nor did they initiate any new processes). Four years after the initial intervention, we find significant longer run impacts of the intervention that combines participation & information. Health care delivery (increased utilization and improved adherence to clinical guidelines) and health outcomes (reduced child mortality and increased weight-for-age and height-for-age for children) improved in the treatment as compared to the control group. For example, the estimated rate-ratio for under-five mortality; i.e., the ratio of the incidence of child deaths in the treatment relative to the control group, implies a 23% reduced risk of under-five deaths in the treatment group.

Without information, there is no impact of the pure participatory intervention

Second, we aimed at disentangling how important information is in these types of participatory processes. In parallel with the long-run follow-up of the participation & information intervention, we initiated a second experiment testing a participation (only) intervention. We implemented the participatory component of the intervention described above (and evaluated in Power to the People), including the three facilitated meetings. But in that participatory experiment we did NOT disseminate any information about the health facility’s performance. No report cards were prepared and shared with the population. Thus, the community now had to build their reform agenda (action plan) on their perceived performance of the local health facility as opposed to the objectively measured performance of the health facility (which was provided to the participation & information intervention group through the information in the report cards).

The impacts of the interventions with and without information differ markedly. Without information, the process of stimulating participation and engagement (the participation intervention) had little impact on the health workers’ behavior, health outcomes or the quality of health care. It seems that information is an important component in community-based interventions.

Using data from the implementation phases of the two interventions, we investigate why the provision of information appears to have played such a key role. A core component of both experiments was the agreement of a joint action plan outlining the community’s and the providers’ agreement on what needs be done, and by whom, in order to improve health care delivery.

While the process of reaching an agreement looks similar on observable measures in the two treatment groups – the same number of community members participated in the community meetings and, on average, the two groups identified the same number of actions to be addressed – the type of issues to be addressed differed significantly.

In the participation group, the health provider and the community identified issues that primarily required third-party actions; e.g., more financial and in-kind support from upper-level authorities. While in the participation & information group, the participants focused to a much larger extent on problems that could be solved locally, and which either the health workers or the community themselves could address.

This is well illustrated in Figure 1. The share of local issues is higher in the participation & information group (blue dots) than in the participation group (red triangles). And the share of local issues correlates positively with the changes in the number of outpatients served by the health facility.

Figure 1: Outpatient care and the share of local issues in the joint action plan

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that lack of information on health facility performance makes it more difficult to identify and challenge (mis)behavior by the provider. That is, with access to information, users are better able to distinguish between the actions of health workers and factors beyond their control and, as a result, turn their focus to issues that they can manage and work on locally. Finally, when the community takes action in monitoring the providers, the health providers exert higher effort and utilization and health outcomes improve.

Martina Björkman Nyqvist is Assistant Professor at the Stockholm School of Economics.

Damien de Walque is Senior Economist in the Development Research Group at the World Bank.

Jakob Svensson is Professor at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.

Join the Conversation