Despite the popularity of business training among policymakers, its use has faced increasing skepticism. Back in 2013, Chris Woodruff and I wrote a review paper (ungated) looking at 13 randomized experiments that tested impacts of training: out of these 13, only 1 found a statistically significant (at the 5 percent level) impact on profits and only 2 found statistically significant impacts on sales. While we noted at the time that “many evaluations suffer from small sample sizes, measure impacts only within a year of training, and experience problems with survey attrition and measurement that limit the conclusions one can draw”, this lack of significance has been interpreted by many readers as showing that traditional business training does not work. For example, Fox and Thomas (2016, p.i33) cite this work to conclude that “what is clear is that projects to graduate household enterprises into small business through entrepreneurship training are expensive and do not seem to pay off”, while Brooks et al. (2018, p.197) cite it to write “where formal business classes have been offered to entrepreneurs, they have had limited impact”.

The evidence base has continued to grow, and so I thought it was a good time to revisit this evidence. In a new working paper, I re-assess the evidence for the effectiveness of business training, incorporating both the older literature and these newer studies. I also look at innovations that have been trialed as alternatives to traditional training, and at different approaches to scaling up training to reach tens of thousands or millions of firms on a cost-effective basis.

First, what should we expect training to be able to achieve?

Standard business training programs aim to teach participants a range of better business practices. The first thing we would like to see from training is therefore likely to be that the knowledge of participants increases, and that they are more likely to use these business practices in their businesses. However, ultimately firms and policymakers will mostly want to judge the success of business training on whether it helps firms to survive, sell more, and become more profitable and productive.

However, most training programs are quite short – e.g. five days. How much can we expect to happen after five days? I provide two benchmarks to help fix ideas of what is a realistic effect size to expect:

· Returns to education benchmark: the returns to a full year of formal education in the average developing country is 7.6 percent. Since 5 days is only about 1/30th of a school year, we might expect returns from 5 days of training to be only 0.5%. Or even if business training is twenty times as effective as regular education in increasing incomes, we should still only expect a 5 percent increase in profits.

· Returns to capital benchmark: the average start-and-improve your business training costs $177 per firm. Microenterprises have been found to have very high returns to capital of 4-5 percent per month. Even with such a return, a firm might earn $8-9 per month from a capital investment equal to the cost of training, or a 8 to 9 percent increase in profits for a firm earning $100 a month. At market interest rates, the implied return would be even lower.

Using either approach, an increase in profits of 4 to 5 percent from training is likely to compare favorably to both regular education and capital investments, and yet such a return is too low for most experiments to detect.

A meta-analysis of traditional business training

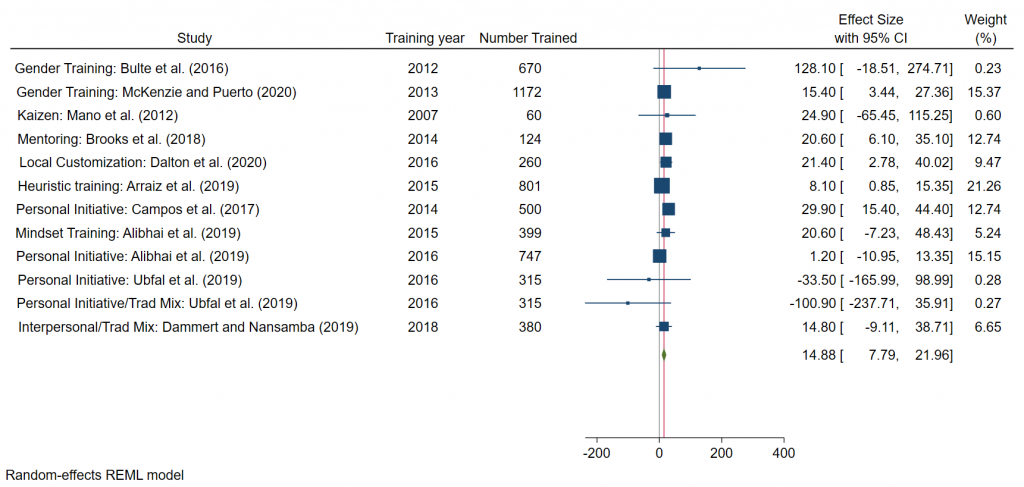

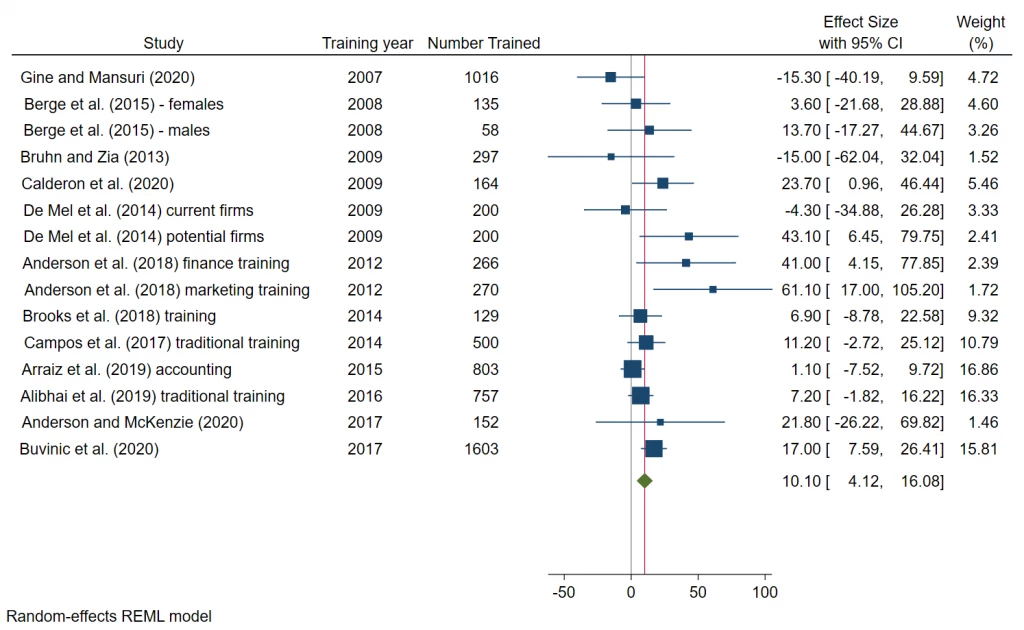

While there are definite limits in the comparability of training and estimates across studies, there are now enough studies that aim to measure the impact of some form of standard business training that I was able to do a meta-analysis. Figures 1 (profits) and 2 (sales) show the range of results from different studies in the literature, and then the pooled random-effects estimates.

I get an overall estimate of the effect on profits of 10.1 percent (95% C.I.: +4.1, +16.1), and on sales of 4.7 percent (95% C.I.: +0.2, +9.2). That is, looking at the totality of evidence from all of these studies, one concludes that business training has improved business outcomes, just not be enough to be detectable in most individual studies. The red line shows these average effects, which lie inside the confidence intervals for almost every study. Note also that the meta-analysis puts the largest weights mostly on studies that have happened more recently, while some of the older studies that had small samples and very wide confidence intervals get very little weight.

Figure 1: Estimates of the Impact of Business Training on Firm Profits

Figure 2: Estimates of the Impact of Business Training on Firm Sales

Alternatives to Traditional Training

While business training “works” on average, we might also think there are ways to make it better, or to make it more relevant for different types of businesses. I discuss five different approaches in the paper:

1. Gender-oriented training for women: in addition to teaching business skills, teach women how to help deal with overlapping household and business demands, enter new sectors, bargain better, and overcome stereotypes.

2. Kaizen approaches: add material that uses Japanese lean manufacturing or continuous improvement practices around production and quality improvement to improve small manufacturing firms.

3. Local customization and the use of peers or mentors: use peers or mentors as a complement or substitute to formal classroom training, and as a way of better adapting recommendations to local conditions.

4. Simplifying training through heuristics and rules-of-thumb: rather than trying to teach a full range of general business practices, offers some simple guidelines to help less sophisticated firms, such as techniques to separate household and business accounts, or to avoid stockouts.

5. Use psychology to develop alternative dimensions of entrepreneurial skills: an example is personal initiative training, which aims to develop a proactive entrepreneurial mindset, such as constantly searching for new opportunities, being self-starting, learning from errors and feedback to overcome obstacles, and thinking of ways to differentiate oneself from other businesses.

Figure 3 shows that the average impact of these alternatives to traditional training is a 14.8 percent increase in profits (95% C.I.: +7.8, +22.9). This is higher than the 10.1 percent average impact of traditional training, but the confidence intervals overlap, and the heterogeneity in impacts amongst studies is much larger than the differences between traditional training and its alternatives. Likewise, the average impact in Figure 4 on revenue of 11.3 percent (95% C.I.: +2.9, +19.7) is higher than the average impact of traditional training on revenue of 4.7 percent, but with the confidence intervals again overlapping. This accords with the results of several of the studies which have tested an alternative against traditional training and found somewhat larger impacts of the alternative, but often without being able to reject equality. The results suggest the promise of using some of these approaches to improve on standard training.

Figure 3: Impact on Profits of Alternatives to Traditional Training

Figure 4: Impact on Sales of Alternatives to Traditional Training

How can we scale up training to reach many more firms?

Most experiments have been done as pilots with relatively small numbers of firms. Developing countries have hundreds of thousands, or millions of such small firms – for example, the Mexican Economic Census enumerated 4.1 million firms with 0 to 10 workers. I discuss three potential approaches in the paper for helping scale up training to reach many more firms in a cost-effective manner.

1. Charging firms for training and developing the market for business services: many governments and NGOs give away training for free. I discuss new evidence on how to price training, and on whether getting firms to use the market can be effective.

2. Using online technologies such as edutainment, SMS, and online lessons: edutainment television shows and SMS messages are cheap ways of reaching large numbers, but have very small average effects. Especially now with COVID-19, there is increasing interest in teaching business skills online, but little evidence so far as to its effectiveness.

3. Filter or funnel firms to offer more support to those who will benefit the most/better targeting: Any business training program is unlikely to offer equal benefits to all firms taking it. The challenge is trying to best target programs to those firms that will benefit more. I discuss potential ways to do so, but evidence is limited.

Still a lot to learn

With this growing body of work, we now have a much better evidence base than was the case even five or six years ago. Indeed, researchers now worry that they will struggle to publish “yet another business training paper”. But doing this new review reiterated to me how much we have collectively learned through the accumulation of evidence, and also how many unanswered questions there still are. If we compare the number of papers on business education to those on general education in schools, it is also apparent how few studies there still are. I therefore encourage researchers, and especially editors, referees, and funders, to continue to support more work in this area.

Join the Conversation