In the closing scene of Christopher Nolan’s

The Dark Knight, Police Commissioner Gordon tells his son that Batman is “the hero Gotham deserves but not the one it needs right now” (

video). This quote provides an interesting policy analogy with minimum wage increases. The benefits of raising minimum wages are something we believe workers deserve: better pay. Unfortunately, the costs tend to involve higher unemployment, which no country needs right now.

There is an extensive literature in developed countries that studies minimum wage hikes. This research has found higher minimum wages can lead to job losses, no effect on jobs, or even job growth ( Neumark and Wascher 2008 provides one of many reviews). Minimum wages in developing countries tend to be set higher, are less likely to be rigorously enforced, and labor markets are often segmented into formal and informal sectors with minimum wage policy only covering formal workers. Given these differences and that most developing countries implement minimum wage policies, understanding their consequences on labor markets is critical for economic growth, developing effective labor policy, and poverty alleviation.

My job market paper studies the impact of minimum wage policy on labor market outcomes and poverty in Honduras from 2005-2012 using repeated cross-sections of household survey data. The attributes of Honduran minimum wage policy and its labor market are similar to many developing countries, so the resulting conclusions from this case study may extend beyond its borders.

The empirical problem and my solution

Determining whether the benefits of minimum wages offset their costs is more complicated than it seems. The difficulty arises because minimum wage increases are endogenous, set in response to previous economic conditions that also affect earnings and employment such as growth or recession, inflation, and changing demand for goods and services over time. Most minimum wage studies in developing countries avoid endogeneity problems by exploiting a source of exogenous variation, often due to a policy change or natural experiment. While the majority of them use a single minimum wage shock for identification, I am able to employ a strategy that exploits multiple sources of variation: annual reforms to minimum wages, a large average increase, and institutional changes in the number of minimum wages.

Honduras sets multiple minimum wages that differ across region, industry, and firm-size categories. The category-level structure is my main source of variation, which exploits different rates of change across categories (much like using state-level differences in the US). Three events affect these rates of change from 2005-2012. First, annual reforms to minimum wages provide variation over time. Second, President Manuel Zelaya raised average real minimum wages by 60 percent in 2009. His intention was to equalize minimum wages across categories. The amount of the increase was unexpected, unrelated to aggregate economic conditions, and uncorrelated to previous electoral outcomes. Last, the number of minimum wages changed from 23 industry firm-size categories in 2005-2008 to 2 urban/rural categories in 2009, then to 6 urban/rural and firm-size categories in 2010, before permanently returning to a structure with 37 industry firm-size categories in 2011.

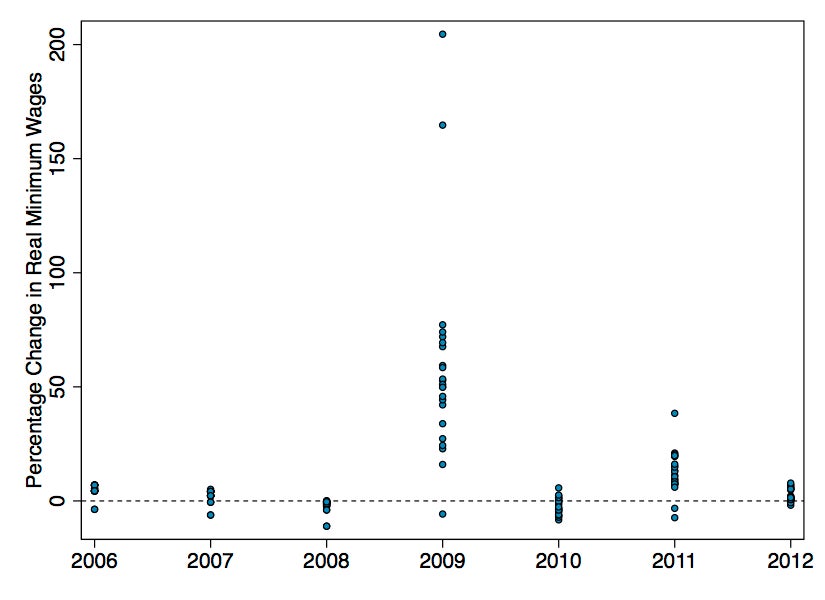

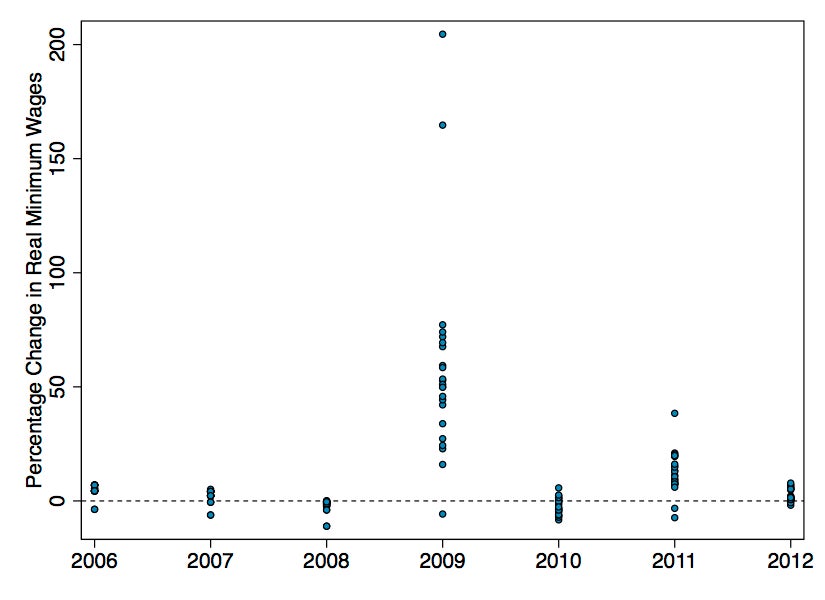

Real hourly minimum wages in this period went from US$0.70 in 2005 to US$1.26 in 2012, and are within range of more than thirty developing countries. On average, Honduran minimum wages increased by 10.8 percent over this period, but variation across the 23 initial categories includes declines of -11.1 percent (because of inflation) and increases as high as 204.5 percent, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Annual variation across minimum wage categories

I employ a difference-in-differences strategy that compares individuals in high vs. low minimum wage categories over time. After controlling for covariates, category fixed effects, and time dummies, all remaining within-category variation over time is plausibly exogenous and identifies the net effect of minimum wage hikes.

Results

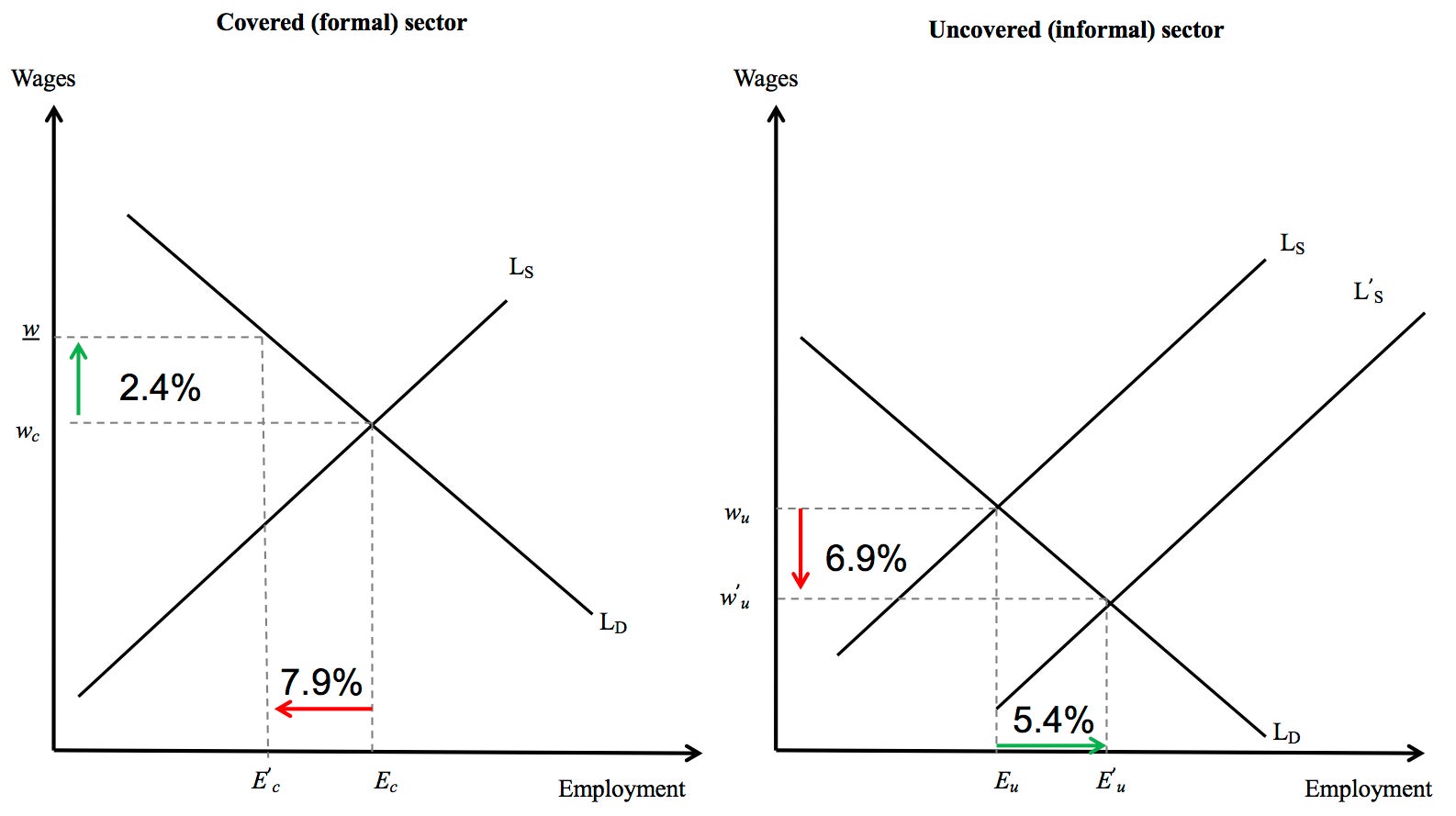

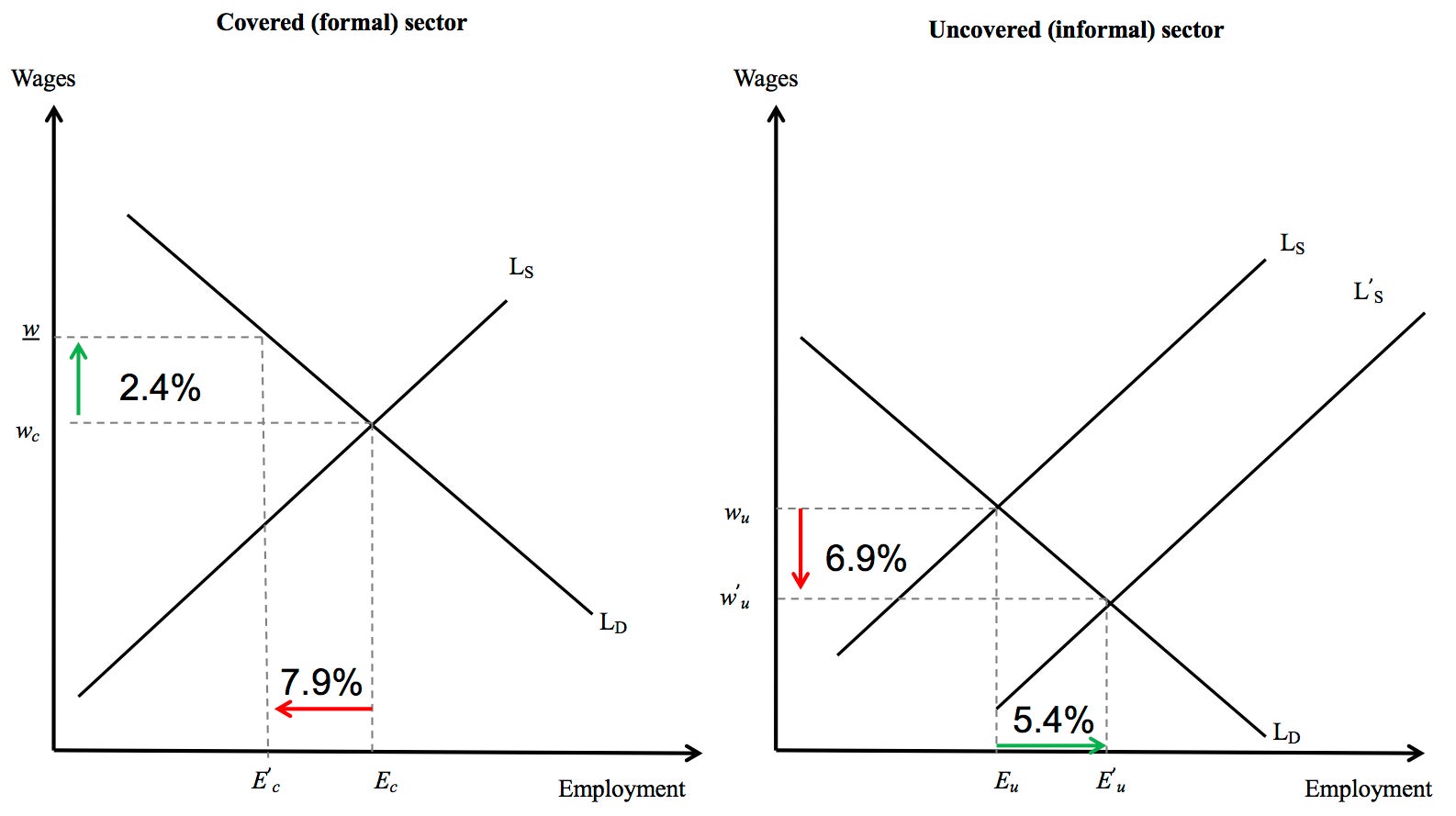

I find that a 10 percent increase in minimum wages reduces employment rates by about 1 percent. Because this result lumps formal and informal sectors together, it disguises the real effect: a significant change in labor force composition. The same minimum wage hike lowers the likelihood of employment in the formal sector by about 8 percent and increases the probability of employment in the informal sector just over 5 percent. The data indicate that individuals substitute wage earning jobs for self-employment as a direct consequence of minimum wage hikes. Wages in the formal sector increase but the observed influx of workers towards the informal sector leads to a negative net effect on informal sector wages. Figure 2 depicts these results.

Figure 2: Labor market effects of minimum wages in Honduras

Since informal sector jobs tend to be lower-paid part-time positions, average earnings in this sector often lie below formal sector incomes. Hence, there may be an adverse effect on individual well-being from these observed changes in labor force composition. To approximate the welfare effect of minimum wages, I estimate whether minimum wage increases help workers escape from extreme poverty. I find that a 10 percent increase in minimum wages has a negative but statistically insignificant effect on the risk of extreme poverty for the formal labor force. The same minimum wage hike significantly raises the risk of extreme poverty for the informal workforce by around 4 percent. This result indicates that on balance, higher minimum wages increase poverty.

I also find evidence that more formal workers are being paid less than the minimum wage. This occurs despite formal employers’ legal obligation to comply with minimum wages. Some non-compliance has always been observed in developing countries, mostly in response to imperfect enforcement from regulators ( Rani et al. 2013). In Honduras, about one in three formal workers earns sub-minimum wages. As minimum wages increase, so does the level of non-compliance. I estimate that about 36 percent more formal sector workers, who should be receiving minimum wages, are underpaid by their employers.

These results are robust to alternative estimation procedures and when including linear category-specific trends to account for heterogeneous time effects across categories as well as relaxing the parallel trends assumption ( Allegretto et al. 2013). I also aggregate the data to the category-level and obtain similar but insignificant estimates due to a loss of power (as shown by Bertrand et al. 2004). One drawback of my study is that I cannot observe the same individuals over time. Panel data would help track worker flows and allow estimating a structural or behavioral model. Another limitation is that measurement error in the surveys could impact my results but predicting the direction of any response bias is problematic.

Policy Implications

My findings imply that the costs of minimum wage increases outweigh their benefits in developing countries. The policy implication is that setting high minimum wages has detrimental effects on labor markets, well-being, and compliance. While Honduran minimum wage policy is unlikely to offer a template for other nations, it provides a cautionary tale. Raising minimum wages may significantly alter the landscape of the labor market. To fully determine the policy’s long-term consequences, we need to better understand the informal economy. Jobs in this sector range from street vendors to moto-taxi drivers. Because informal activities are becoming more commonplace across the developing world, we must learn why people enter this sector and the consequences of participating in such activities.

This evidence acknowledges that minimum wage policies in developing countries may not provide what workers deserve or need. However, knowing its flaws can helps us steer this labor policy towards the goals we would like it to accomplish. Even Batman has occasionally changed his own approach.

Andrés Ham is a Ph.D. candidate in Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His website can be found here .

There is an extensive literature in developed countries that studies minimum wage hikes. This research has found higher minimum wages can lead to job losses, no effect on jobs, or even job growth ( Neumark and Wascher 2008 provides one of many reviews). Minimum wages in developing countries tend to be set higher, are less likely to be rigorously enforced, and labor markets are often segmented into formal and informal sectors with minimum wage policy only covering formal workers. Given these differences and that most developing countries implement minimum wage policies, understanding their consequences on labor markets is critical for economic growth, developing effective labor policy, and poverty alleviation.

My job market paper studies the impact of minimum wage policy on labor market outcomes and poverty in Honduras from 2005-2012 using repeated cross-sections of household survey data. The attributes of Honduran minimum wage policy and its labor market are similar to many developing countries, so the resulting conclusions from this case study may extend beyond its borders.

The empirical problem and my solution

Determining whether the benefits of minimum wages offset their costs is more complicated than it seems. The difficulty arises because minimum wage increases are endogenous, set in response to previous economic conditions that also affect earnings and employment such as growth or recession, inflation, and changing demand for goods and services over time. Most minimum wage studies in developing countries avoid endogeneity problems by exploiting a source of exogenous variation, often due to a policy change or natural experiment. While the majority of them use a single minimum wage shock for identification, I am able to employ a strategy that exploits multiple sources of variation: annual reforms to minimum wages, a large average increase, and institutional changes in the number of minimum wages.

Honduras sets multiple minimum wages that differ across region, industry, and firm-size categories. The category-level structure is my main source of variation, which exploits different rates of change across categories (much like using state-level differences in the US). Three events affect these rates of change from 2005-2012. First, annual reforms to minimum wages provide variation over time. Second, President Manuel Zelaya raised average real minimum wages by 60 percent in 2009. His intention was to equalize minimum wages across categories. The amount of the increase was unexpected, unrelated to aggregate economic conditions, and uncorrelated to previous electoral outcomes. Last, the number of minimum wages changed from 23 industry firm-size categories in 2005-2008 to 2 urban/rural categories in 2009, then to 6 urban/rural and firm-size categories in 2010, before permanently returning to a structure with 37 industry firm-size categories in 2011.

Real hourly minimum wages in this period went from US$0.70 in 2005 to US$1.26 in 2012, and are within range of more than thirty developing countries. On average, Honduran minimum wages increased by 10.8 percent over this period, but variation across the 23 initial categories includes declines of -11.1 percent (because of inflation) and increases as high as 204.5 percent, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Annual variation across minimum wage categories

I employ a difference-in-differences strategy that compares individuals in high vs. low minimum wage categories over time. After controlling for covariates, category fixed effects, and time dummies, all remaining within-category variation over time is plausibly exogenous and identifies the net effect of minimum wage hikes.

Results

I find that a 10 percent increase in minimum wages reduces employment rates by about 1 percent. Because this result lumps formal and informal sectors together, it disguises the real effect: a significant change in labor force composition. The same minimum wage hike lowers the likelihood of employment in the formal sector by about 8 percent and increases the probability of employment in the informal sector just over 5 percent. The data indicate that individuals substitute wage earning jobs for self-employment as a direct consequence of minimum wage hikes. Wages in the formal sector increase but the observed influx of workers towards the informal sector leads to a negative net effect on informal sector wages. Figure 2 depicts these results.

Figure 2: Labor market effects of minimum wages in Honduras

Since informal sector jobs tend to be lower-paid part-time positions, average earnings in this sector often lie below formal sector incomes. Hence, there may be an adverse effect on individual well-being from these observed changes in labor force composition. To approximate the welfare effect of minimum wages, I estimate whether minimum wage increases help workers escape from extreme poverty. I find that a 10 percent increase in minimum wages has a negative but statistically insignificant effect on the risk of extreme poverty for the formal labor force. The same minimum wage hike significantly raises the risk of extreme poverty for the informal workforce by around 4 percent. This result indicates that on balance, higher minimum wages increase poverty.

I also find evidence that more formal workers are being paid less than the minimum wage. This occurs despite formal employers’ legal obligation to comply with minimum wages. Some non-compliance has always been observed in developing countries, mostly in response to imperfect enforcement from regulators ( Rani et al. 2013). In Honduras, about one in three formal workers earns sub-minimum wages. As minimum wages increase, so does the level of non-compliance. I estimate that about 36 percent more formal sector workers, who should be receiving minimum wages, are underpaid by their employers.

These results are robust to alternative estimation procedures and when including linear category-specific trends to account for heterogeneous time effects across categories as well as relaxing the parallel trends assumption ( Allegretto et al. 2013). I also aggregate the data to the category-level and obtain similar but insignificant estimates due to a loss of power (as shown by Bertrand et al. 2004). One drawback of my study is that I cannot observe the same individuals over time. Panel data would help track worker flows and allow estimating a structural or behavioral model. Another limitation is that measurement error in the surveys could impact my results but predicting the direction of any response bias is problematic.

Policy Implications

My findings imply that the costs of minimum wage increases outweigh their benefits in developing countries. The policy implication is that setting high minimum wages has detrimental effects on labor markets, well-being, and compliance. While Honduran minimum wage policy is unlikely to offer a template for other nations, it provides a cautionary tale. Raising minimum wages may significantly alter the landscape of the labor market. To fully determine the policy’s long-term consequences, we need to better understand the informal economy. Jobs in this sector range from street vendors to moto-taxi drivers. Because informal activities are becoming more commonplace across the developing world, we must learn why people enter this sector and the consequences of participating in such activities.

This evidence acknowledges that minimum wage policies in developing countries may not provide what workers deserve or need. However, knowing its flaws can helps us steer this labor policy towards the goals we would like it to accomplish. Even Batman has occasionally changed his own approach.

Andrés Ham is a Ph.D. candidate in Agricultural and Applied Economics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His website can be found here .

Join the Conversation