First, how much of a home bias is there?

I thought I would put numbers to Paolo’s casual observation. The job market seems a reasonable place to start, since people have a designated job market paper, many people list citizenship on their C.V., or other features that can be used to determine citizenship, and it captures the country choices of students before they have found jobs. The latter point is important if the choice of country to work on affects the position these students end up receiving.

Looking at job market students at 20 top universities in the U.S., U.K. and France, I count 29 Ph.D. students on the economics job market who list development economics as one of their fields, and who are from a developing country.

- Home bias is prevalent: 24 of the 29 students (83%) had a job market paper on their country of origin. Only Colombians were more likely to work on another country than their home country (4 out of 7 were working on other countries, such as Mexico and Peru).

Pros and Cons of this for Individual Researchers

I then opened up a debate on twitter by wondering whether it helps or hurts a job candidate to work on their own country. The pros of working on a country you know well are quite obvious: you are likely to have a comparative advantage in doing work in this country for many reasons – you speak the language; have much better knowledge of important institutional and contextual features that affect economic behavior; potentially have connections that help access local data sources or set up interesting interventions with schools, firms, or government policies; and you may be more intrinsically motivated to do this work if you feel it is helping people in your home country. In our interview with Rohini Pande, she provides more reasons in her first response, noting the importance of understanding power structures, and of Jean Dreze saying “Once I got to India, there was more than enough for me to do in a lifetime”.

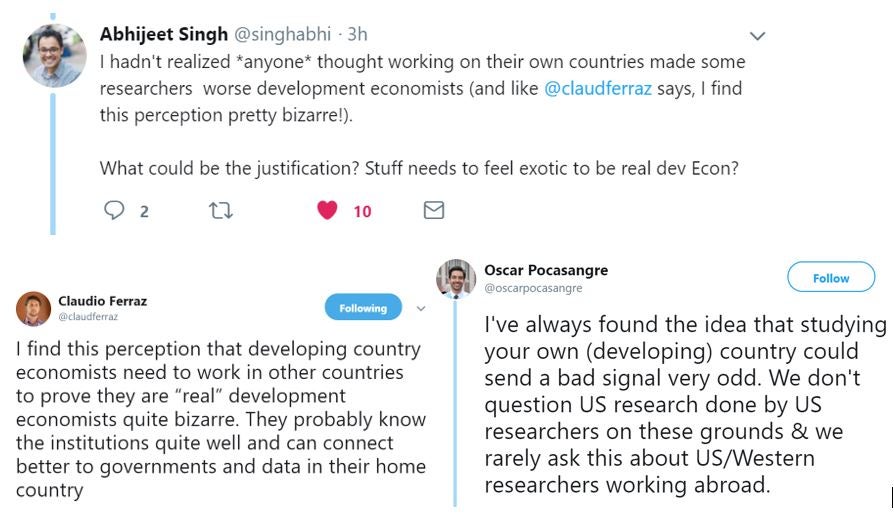

Given these pros, several development economists and political scientists pushed back strongly, questioning how anyone could view it as a negative, and noting a double-standard with how we treat U.S. researchers working on the U.S. E.g.

So does anyone think the market could view working on your own country as a development economist on the job market as anything but a good thing? I ran a twitter poll to get some sense of how common this view was (within the obvious limits of self-selected responses):

We see 90 respondents thought it was viewed as a negative, almost as many as viewed it as a positive (and that the most common response is to just be curious what others say without offering an opinion yourself).

So how could this be seen as a negative?

A first point to note on this is that the types of questions researched may differ depending on whether you are from a country or not. Being too familiar with an issue may prevent you from questioning certain behaviors or seeing that there could be other ways of doing things. Alexei Abrahams noted “Those political connections often indicate the researcher herself is embedded in a network of privilege within that country. How does that shape their research agenda -- esp. their views on political reform?”. But this might just affect how a particular piece of research is viewed, not the signal contained in it about the researcher behind it.

Here is a toy model to illustrate how I think some potential negative signal may be inferred from working on your own country. Suppose that we model a research production function as Y* = f(general human capital G, local knowledge L), and then what I observe is a binary outcome Y = 1 (complete paper of good quality) if Y*>0, and Y = 0 (don’t complete paper of good quality) if Y*0 (that is, all else equal, having local knowledge produces better research).

Then if I observe a good job market paper (Y=1), what do I infer about their general human capital G of the author? If they do not have local knowledge, then there is some general human capital cut-off G1, where I can infer that their G>G1. But precisely because local knowledge makes it easier to conduct high quality research in a country, if I know an author has local knowledge, then all I can infer is that G>G2 for some G2

Some implications of a model like this are:

Implication 1: the more what you do depends on local knowledge, the less one can infer about your general human capital. I think this is particularly an issue if the main innovation in your paper is around identification or description, such as identifying an amazing regression-discontinuity because of some local policy, convincing a policymaker to randomize something that others could not imagine being randomized, or having amazing descriptive results because of special data only available in that country. In contrast, if your paper makes a contribution with theory, new empirical techniques, adds a structural model, etc. and the particulars of the specific country that you apply it to are only one component of your paper, then this point becomes less relevant.

Implication 2: whether it matters depends on whether I expect you to need to work on other countries. The above discussion assumed I care about your G, and not just your output Y. There are two reasons why I might care about G –because I want to predict whether you can continue to produce excellent research in the future, and also perhaps because I think it correlates with the value you can add to students and colleagues. But, of course plenty of people successfully make a career working on one country, and often helping their colleagues to work in that country too (this obvious for people working on the U.S., but also true for people working on countries like China, India and Brazil). It is more of a concern if you come from a tiny country (like I do), where the range of questions you can answer that are likely to be of broad general interest may be narrower. This is not just an issue for development economics – great papers written on Sweden or Israel (or New Zealand) for example may raise similar questions. It is perhaps less of a concern for those pursuing a self-directed research career than for those seeking jobs that will require them to work in multiple countries.

Note also that this is really just an issue early in your career – a lot of the uncertainty about your ability to keep producing interesting papers gets resolved by seeing you do it multiple times.

So does this model mean you shouldn’t work on your own country?

Not at all. I am sure many readers will object to many of the assumptions in the above model, and by changing these assumptions, you may get very different implications. For example, if instead of calling L local knowledge, I called it advisor’s knowledge and contacts, then the same model would say there is a negative signal in working on the same topic or in the same country as your advisor. As one of my colleagues noted to me, being local isn’t the only way or necessarily even the best way to get access in a country, and what my model calls “general human capital” might just reflect that certain privileged groups always find it easier to get access to grants, policymakers, and other tools that help their research.

This highlights the

reductio ad absurdum of such a model – it would imply the strongest signal of your general human capital is to work on a topic for which it is hard to get funding, where neither you nor your advisor has any existing knowledge of, has no local context for, and is super-difficult to pull off. It is far from clear that you are demonstrating how smart you are by doing so – i.e. by showing you are an economist who ignores comparative advantage.

This highlights the big problem with the “all else equal” statements in the above discussion. Even in this model, better local knowledge makes it more likely that you will be able to write a good paper in the first place (or in a more general model, a great rather than just good paper). Furthermore, even for a given paper quality, if it takes you less effort to do with high local knowledge, this frees up time to make additional contributions in other papers.

Implications of Home Bias for Recruiting into the Profession

It is hard to do good research, especially when starting off in the profession. The last thing I want to do is scare someone away from working on a country that they know a lot about and are passionate about, because of a fear of the signal it sends. As I’ve argued above, there are many reasons why working on your home country can result in better research, and I think the signaling model has big limits, and can just as easily be used to say there is just as much uncertainty about the general human capital of anyone who is using any form of comparative advantage. The profession has a problem with diversity, and we need more contributors from developing countries. As Dina Pomeranz noted:

This suggests a societal cost of home bias is that if people prefer to work on their own countries, a lack of diversity in where Ph.D. students are recruited from will result in a lack of diversity in which countries are researched. In the sample of Ph.D. students on the market that I looked at, three countries (India, Colombia, China) account for 22 of the 29 students. When combined with home bias, the result is that these three countries account for 59% of the job market papers by developing country researchers at these 20 institutions. So this is another reason to diversify the pipeline into Ph.D. programs in development economics.

Join the Conversation