We want to increase (girls) education… but what’s the best way to do this?

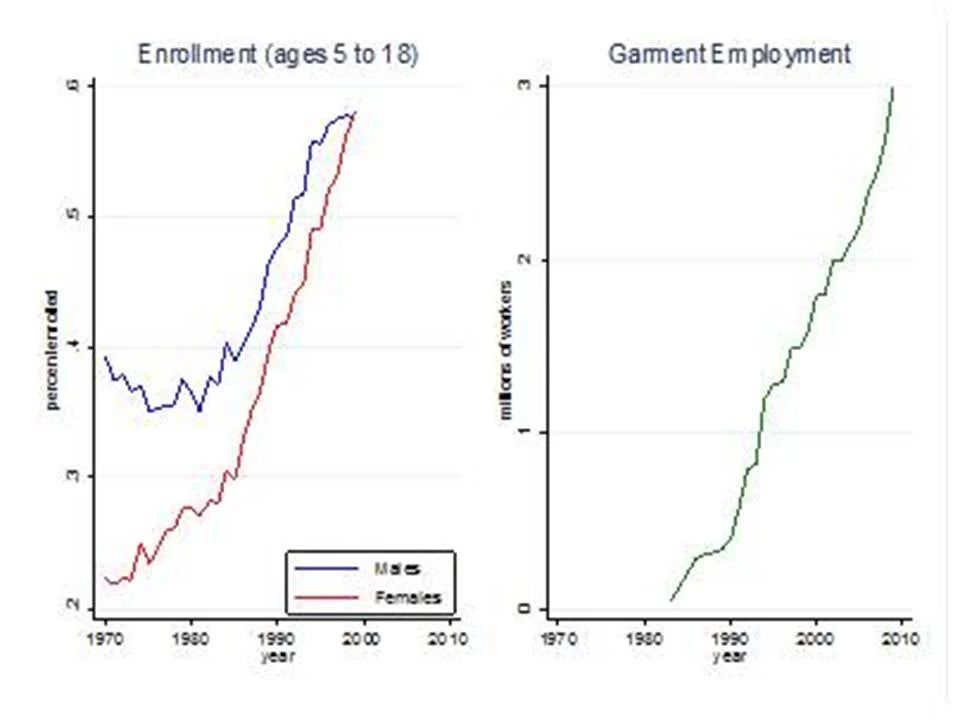

A lot of education policy has been based on the philosophy immortalized in the classic movie Field of Dreams: "Build it and they will come.” That is, researchers and policymakers have examines the effects of programs that lower the direct or indirect costs of schooling, for instance, through building schools (Burde and Linden 2010), providing conditional cash transfers to parents (Fiszbein and Schady 2008 and references therein) or directly to students (Baird, McIntosh, and Ozler 2011) or inputs such as textbooks (Glewwe, Kremer, and Moulin 2009), school meals (Vermeersch and Kremer 2004), or uniforms (Evans et al 2009). There has been comparatively less research on the demand-side determinants of school enrollment, even though recent evidence suggests that enrollment is increased by the arrival of call center jobs in India (Jensen 2011; Oster and Millet 2011) or providing information about wage-education profiles households in the Dominican Republic (Jensen 2010). A recent paper of mine, with Mushfiq Mobarak, assesses whether these types of demand-side effects are important contributors to the dramatic increases of girls schooling in Bangladesh in the past 40 years (see the graph on the left in figure 1).

Specifically, we examine whether the rapid expansion of the garment industry, which took place over roughly the same period (the right hand side of figure 1), lead to increases in school enrollment, particularly for girls. While there is no minimum level of schooling required for garment jobs, better jobs require literacy and numeracy to keep written records or follow patterns. Anthropologists and sociologists have argued qualitatively that parents respond to the returns to education in the garment industry: “both urban and rural poor educate their girl children with an intention to engage them in the garment industry” (Pala-Majumdar 2000).

Estimating the impacts of the garment industry

To assess the impacts of the garment industry on schooling, we construct retrospective yearly enrollment data from the schooling histories of the households in a survey we conducted in four subdistricts located just outside of Dhaka in 2009. Of the sixty villages in the sample, 44 were classified by a garment industry executive as within commuting distance of garment factories, and 16 control villages were not considered to be within commuting distance. The key estimation challenge, of course, is that garment factories were not placed at random. In fact, it’s important to acknowledge that there are statistically significant “pre-treatment” differences between the garment villages and non-garment villages in our sample: garment villages are closer to Dhaka, and have significantly higher levels of schooling (though more strikingly for males than females) among adults over 50, who would have finished their schooling before the garment industry began.

We address those challenges in a couple ways. First, since we have data on enrollments going back to the years before the garment industry began, we can use a difference-in-difference type strategy to estimate the effects of the increase in garment sector jobs by comparing the enrollment outcomes of siblings in garment villages with relatively greater exposure to the growth in the garment sector versus siblings with relatively less exposure to garment jobs, and comparing this difference to siblings pairs in non-garment villages. We also assess whether the effects of the growth in the garment sector are higher for girls than for boys (a triple-difference strategy), since the garment sector provided new employment opportunities predominantly for females. This strategy allows for there to be shocks to enrollment at the same time garment factories arrive, as long as they affect girls and boys similarly. We further argue that even if the type of complimentary infrastructure that tends to attract factories (such as a road leading to the village or electrification) differentially impacts girls’ enrollment relative to boys – say, if girls’ enrollment is more elastic with respect to travel time than boys’ (Glick 2008) – these tend to be primarily one-time investments needed before factories come. That is, if enrollment effects were due to complementary infrastructure improvements, we’d see large jumps when the garment industry first began, but no little or no effects afterwards. Finally we test for differential pre-garment industry trends in enrollment (which we might see if factories tended to locate in areas where girls’ schooling was expanding already) and do not find any evidence of them, whereas we see continued effects throughout the expansion of the garment industry.

What do we learn from these estimates?

Our results suggest that the garment industry has lead to increases in girls schooling and has had a negligible impact on boys schooling. Overall girls' enrollment increases by 0.71 of a percentage point (relative to boys in the same family) when there is a 10 percentage point increase in the number of garment jobs available. The estimated effect is borderline significant (P = 0.180). When we look at older and younger girls separately, we find a larger (and statistically significant) effect of the increase in garment jobs on the schooling of younger girls. By contrast, there is a net zero effect on older girls, some of whom likely drop out to access the jobs right away.

Interestingly, these effects are present even among girls whose mothers have never worked outside the home, suggesting that the effects are not entirely due to income effects from mothers working in the garment industry. Rather, increases in enrollment seem to be driven at least partially by returns to education in the new garment jobs. Another potential channel for the new garment jobs to increase the enrollment of daughters whose mothers do not take the jobs is that the new jobs improve the outside option – and therefore, the bargaining power—of mothers who are not currently working outside the home (Majlesi 2011).

To provide further evidence on whether the enrollment effects of the garment industry were tempered by girls who drop out of school to access garment jobs, we test whether garment jobs led to greater increases in enrollment after 1993, when bad publicity from the proposed Child Labor Deterrence Act in the U. S. lead many garment factories in Bangladesh to stop the use of child workers (Rahman et al 1999 and newspaper articles cited therein). When we allow the effects of the garment industry to vary before and after 1993, we find suggestive evidence that the relationship between the garment industry and girls’ schooling was much stronger after 1993. That is, once there was no longer a possibility to drop out of school to take new garment jobs, families were even more likely to decide to keep their daughters in school in response to new garment sector jobs.

While much policy attention has been devoted to interventions that decrease the cost of education, policy can affect demand-side factors as well. For instance, trade policy or domestic industrial policy can promote the arrival of jobs that require education. Our results on child labor imply that these effects will be even stronger if job-promoting policies are paired with monitoring that insures that younger children are not dropping out of school to access these jobs. More broadly, our results suggest that policymakers interested in increasing education should devote more attention to why households in developing countries whose children are not enrolled in school may not find education valuable.

Rachel Heath is a postdoc at the World Bank and starting in fall 2012 will be an assistant professor of economics at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Join the Conversation