It is hard to teach people new things, especially when they have limited time to learn. Business training programs face this challenge. A typical program attempts to teach an entrepreneur a whole range of accounting, marketing, human resource, and other business practices in 3 to 12 days. On average, these programs improve business practices around 5 percentage points, so that if you try to teach 20 new practices, firm owners end up adopting 1 of them. As discussed in a recent post and paper, this does result in an improvement in firm outcomes, but this improvement is often hard to detect and necessarily limited by the relatively small change in practices.

In a new working paper, Steve Anderson and I conduct an experiment to test whether an alternative approach to improving business skills in firms may be more successful: helping entrepreneurs use markets to hire someone who already is a specialist in these practices. Our motivation is that in larger firms, it is common for the owner to hire someone else to keep financial accounts or do the firm’s marketing – Figure 1 shows this for a sample of over 8,000 Nigerian firms that applied to a government program. So, if we start with growth-oriented firms with a few workers and hope to get them to grow to have 10, 20 or more workers, perhaps we should help the entrepreneurs directly jump to this stage. In the language of our paper, we suggest not only considering the traditional boundary of the firm (which tasks should be done by the firm versus outside) but also the boundary of the entrepreneur (which tasks should the entrepreneur do him or herself, versus get others to do).

Figure 1: Entrepreneurs are less likely to do the finance and marketing tasks in larger firms

Testing insourcing and outsourcing as an alternative to business training

The opportunity to test this idea arose in the context of the Growth and Employment (GEM) project in Nigeria. This project aimed to work with small firms in five sectors - light manufacturing, ICT, hospitality, entertainment and construction – and help them improve business practices and grow through either business training or consulting. We worked closely with the World Bank operational task leader at the time, Johanne Buba, and the project implementation unit to pilot two alternative approaches and test them through a randomized experiment.

We worked with a sample of 753 firms with 2 to 15 workers, that were based in Lagos or Abuja, and that were not already having someone else do both their accounting and marketing. Almost all entrepreneurs had tertiary education, 44% of firms were run by female owners, and average profits were around US$1,000 per month. These firms were randomly assigned into five groups of approximately 150 firms each:

· Business Training: this group received 25 hours of online training followed by 12 days of in-person training, based on the Business Edge curriculum, and at a cost of approximately $2,000 per firm.

· Consulting: firms were matched to a business consultant who provided 88 hours of personalized consulting spaced over 6 to 9 months at a cost of $4,000 per firm.

· Insourcing: firms were linked to a marketplace of service providers, and given a subsidy they could use to hire a human resources agency to help them hire an accounting or marketing worker. This worker would then work full-time in the firm, with a subsidy paying for their wages on a declining basis over 8 months. The total cost was set approximately equal to the cost per firm given training (US$2,000 per firm).

· Outsourcing: firms were linked to a marketplace of service providers, and given a subsidy they could use to hire a professional marketing or accounting firm to carry out this business function for the firm. This specialist would typically work one day a week for the firm, and the rest of the time for other clients. Again, the subsidy was set so the total cost per firm was approximately equal to that for training, and the subsidy amount declined over time, over a 9 month period.

· Control group: did not receive any of the above programs.

Measuring improvements in business practices

We conducted two follow-up surveys at one and two years after the intervention started to measure impacts. Response rates were reasonably high (89% and 86%) and balanced across the five groups. One of our key outcomes was the business practices firms use. A particular concern in collecting these data after skill-building interventions is the potential of experimenter demand effects or desirability bias, where training might make entrepreneurs aware of which practices are considered desirable, and lead them to claim to be doing certain things to either please the interviewer or try to make themselves look good. We discuss in the paper several approaches we took to mitigate this possibility. One of these was to work hard on obtaining objective measures of some business practices. We measured 41 different business practices representing both traditional activities (in finance/accounting, marketing/sales, operations/HR) and also more novel activities (in digital marketing). For 21 of these practices, we were able to objectively verify them. This occurred in two ways: (1) through the use of photographs and physical observation (e.g. observing whether the firm had a balance sheet, used certain marketing materials, recorded maintenance checks, etc.); and (2) for digital marketing practices, by collecting and auditing digital footprints (e.g. Twitter handles, Facebook page addresses, Instagram pages, Website URLs, etc.).

In addition to measuring the quantity of practices used, for digital marketing we also measured the quality of the practices employed. This involved having a team of independent scorers, blinded to treatment status, score websites, Facebook, Instagram, and twitter pages on key attributes of digital marketing effectiveness including function (e.g. access, usability, recency), information (e.g. content, contact information, value proposition), emotion (e.g. aesthetics, engagement) and action (e.g. promotions, differentiation).

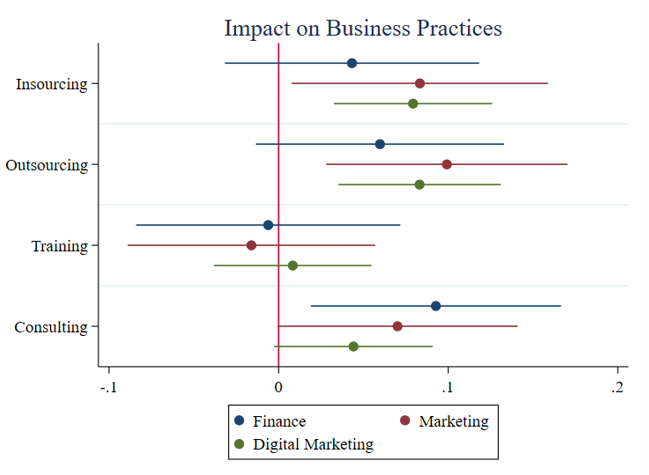

Figure 2 summarizes impacts on the proportion of finance, marketing, and digital marketing practices implemented by firms. Business training had no significant impact on any of these measures, with the confidence interval encompassing the 5 percentage point change in practices common in the literature. We see statistically significant and much larger improvements from the three market-based approaches, with the insourcing and outsourcing particularly good at improving marketing and digital marketing practices – most firms chose this type of specialist. Impacts were particularly large for particular types of new digital technologies like using a customer relationship management system (15-17 p.p.), setting up a business website (13-17 p.p.) and having a business Facebook page (20-23 p.p.), and a business Instagram (12 p.p.). As well as improving the quantity of practices, we find the quality of these practices to also be better in the new insourcing and outsourcing treatments.

Figure 2: Impacts on Business Practices after Two Years

From business practice improvements to firm growth

We had planned to have a sample of 2,000 firms, with 400 in each group. This was to be made up of different cohorts of firms in the program. However, after our initial recruitment batch, program implementation hold-ups meant more firms could not be added. The result is that we have less power for looking at firm outcomes than intended, and for examining whether this program works differently for male versus female owners, for owners in different sectors, or other types of heterogeneity that would be interesting.

Nevertheless, we find that outsourcing and consulting resulted in significant improvements in sales, profits, and employment. We can not reject that the insourcing intervention had the same effect as these other two approaches, but also can not reject that it had no effect. The main mechanisms seem to be that the firms learned more about what their customers wanted, and introduced new products to meet their needs, and were able to attract more customers through better digital marketing – especially social media technology. Using the estimated treatment effect on levels of monthly profits in the second survey round of $98 per month, the outsourcing treatment would cover the costs of the subsidies ($1,315) in just over one year, and the costs of the full program ($2,000) in under two years. Revealed preference also suggests the program was useful to firms - firms kept at least one-third of their specialists after the subsidy period ended, and were more likely to go back to the market to buy more services.

Do we need more fish shops and fewer fishing lessons?

We see these insourcing and outsourcing approaches as new tools in the arsenal of governments aiming to help firms grow. It requires firms to be on a path where they can support this extra worker or financing this business function, so won’t be appropriate for most one or two person firms. But for firms that have a few workers and are looking to grow further, we think asking what business functions should lie within the boundary of the entrepreneur and which should be outside is a useful question. Governments can then work to help the market for these services work more efficiently (through helping business service providers develop reputations, making it easier for firms to know which providers are good), as well as for subsidizing the initial use of this market as a substitute for spending on some types of training.

Want more: here is a podcast I did with NOVAFRICA discussing this paper.

Fun Bonus: SBMC comic on teaching a man to fish meets political economy.

Join the Conversation