At a recent seminar someone joked that the effect size in any education intervention is always 0.1 standard deviations, regardless of what the intervention actually is. So a new study published last week in Science which has a 2.5 standard deviation effect certainly deserves attention. And then there is the small matter of one of the authors (Carl Wieman) being a Nobel Laureate in Physics and a Science advisor to President Obama.

I was intrigued, especially when I saw the Associated Press headline “It's not teacher, but method that matters” and this quote from Professor Wieman “This is clearly more effective learning. Everybody should be doing this. ... You're practising bad teaching if you are not doing this.” I therefore read the actual article in Science (3 pages [with 26 pages of supporting online material]) and have been struggling since with how to view this work.

So let me start by telling you what this intervention actually was:

Context: the second term of the first-year physics sequence taken by all undergraduate engineering students at the University of British Columbia, Canada. The class was taught in three sections, each by a different instructor. Two of the instructors agreed to take part in the intervention, so their classes were used.

Sample: 2 sections of the same class at UBC. Just over 250 students in each section.

Intervention: The sections were taught the same for 11 weeks. Then in the 12th week, one of the sections was taught as normal by an experienced faculty member with high student evaluations, while the other was taught by two of Wieman’s grad students (the other two co-authors of this paper), using the latest in interactive instruction. This included pre-class reading assignments, pre-class reading quizzes, in-class clicker questions (using a device like the audience uses to vote with in e.g. Who wants to be a millionaire?), student-student discussion, small-group active learning tasks, and targeted in-class instructor feedback. There was no formal lecturing – the point is that rather than being passive recipients of power-point slides and lectures, everything is interactive, with the instructor responding to clicker responses and what is heard during the student exercises.

Timing: A 12-question quiz on what they had been taught during the week was administered at the end of this 12th week.

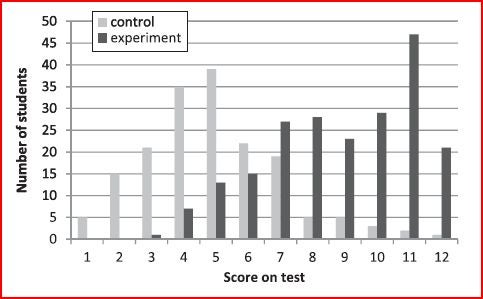

Results: Despite the fact that students were not randomized into the two sections, and that they had had different instructors for 11 weeks before, the students looked similar on test scores and other characteristics before this 12th week. Then the authors find (i) attendance was up 20% in the interactive class; (ii) students were more engaged in class (as measured by third-party observers monitoring from the back rows of the lecture theatre), and (iii) on the 12 question test, students in the interactive class got an average of 74 percent of the questions right, while those taught using traditional method scored only 41 percent – a 2.5 standard deviation effect. This histogram demonstrates how stark the difference in performance was between the two groups.

Source: Figure 1 in Deslauriers et al. (2011), Science 332(862).

My first reaction was “They published this?, it would never get into a top quality Economics journal”. Why?

· I don’t think this even passes my external validity rant criteria – except at most as proof of concept. But performance on 12 questions after one week of one course in one Canadian University seems to be pushing it.

· The 12 questions were written by the grad students teaching the class (and approved by the instructor of the other class), but there are obvious concerns about teaching to the test.

· One week is a really short time to look at effects for- surely we want to see if they persist.

· The graduate students teaching the class certainly had extra incentive to do extra well in this week of teaching.

· The test was done in class, and 211 students attended class in the intervention section, compared to 171 in the control section. No adjustment is made for selection into taking the test- one could imagine for example that the most capable students get bored during regular lectures, and so only start attending when there is something different going on…(or tell a story in the other direction too, the point is some bias seems likely)

· The test was low stakes, counting for at most 3% of final grade.

· Despite them calling this an “experiment”, which it is in the scientific sense of any intervention being an experiment to try something out, there is no randomization going on anywhere here, and the difference-in-difference is only done implicitly.

But on the other hand, having sat through (and taught) a number of large lectures in my time, and having talked to academics who have started using the “clicker”, it does seem plausible that the intervention could have large effects. The experience certainly is interesting, and by sharing it, is likely to motivate others to try it – hopefully in experimental trials with many more classes and subjects to learn whether/how this works best. This got me to start thinking about what we miss in Economics by not having a formal outlet to share results like this – Medical journals have case studies and proof of concept (or efficacy) trial results, and it seems Science does too: 3 pages, published quite fast (the paper was submitted on December 16, 2010 and appeared in print on May 13), of something with a massive effect size – it is hard to argue that we shouldn’t be sharing this information.

Of course, I worry about the media hyping of such a story. The authors humbly enough title the paper “Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class” (emphasis mine) ; but then this becomes “It's not teacher, but method that matters” in the AP, and the public quotes of Professor Wieman are much stronger than those in the article. On the other hand, the New York Times reported the results with reasonable criticism, noting quite a lot of the limitations of the study in its reporting. So some of the media is doing its job….none the less, I do feel uneasy about having press releases about such a slight study – it may be worth sharing with other educators at this stage to encourage more study, but I’m not sure it meets the bar of being worth broadcasting to the World.

So I’m left feeling confused – on the one hand astonished that such a paper is published in a prestigious scientific journal, but on the other hand still wondering what we are missing by not publishing such encouraging early results. It does seem the sort of paper that might cause us to update our priors, even if it doesn’t convince us completely. I think in economics we immediately turn to the “will it work?” questions, without appreciating the “can it work?” evidence enough at times. I can think of several recent economic studies which I might classify similarly (a great example being the work by Pascaline Dupas and Jon Robinson on the impact of a savings account in Kenya – a paper that was done on a small budget while they were students, and has really remarkable results which have got quite a bit of press, even if the data are not always precise and they don’t have enough power to fully nail everything down) – it would be great if Economists could accept and publish such results in a succinct form, as they are, and build on them going forward, rather than the drag it out and focus only on what the study can’t do approach of publishing in economics.

What do you think? Is the economics profession missing insightful experiences from promising new interventions because we only consider the full packaged product? Or have the Science guys got it all wrong?

Join the Conversation