Between 2008 and 2010, we hired a multinational consulting firm to implement an intensive management intervention in Indian textile weaving plants. Both treatment and control firms received a one-month diagnostic, and then treatment firms received four months of intervention. We found (ungated) that poorly managed firms could have their management substantially improved, and that this improvement resulted in a reduction in quality defects, less excess inventory, and an improvement in productivity.

Should we expect this improvement in management to last? One view is the “Toyota way”, with systems put in place for measuring and monitoring operations and quality launch a continuous cycle of improvement. But an alternative is that of entropy, or a gradual decline back into disorder – one estimate by a prominent consulting firm is that two-thirds of transformation initiatives ultimately fail. In a new working paper, Nick Bloom, Aprajit Mahajan, John Roberts and I examine what happened to the firms in our Indian management experiment over the longer-term.

What happened to management practices?

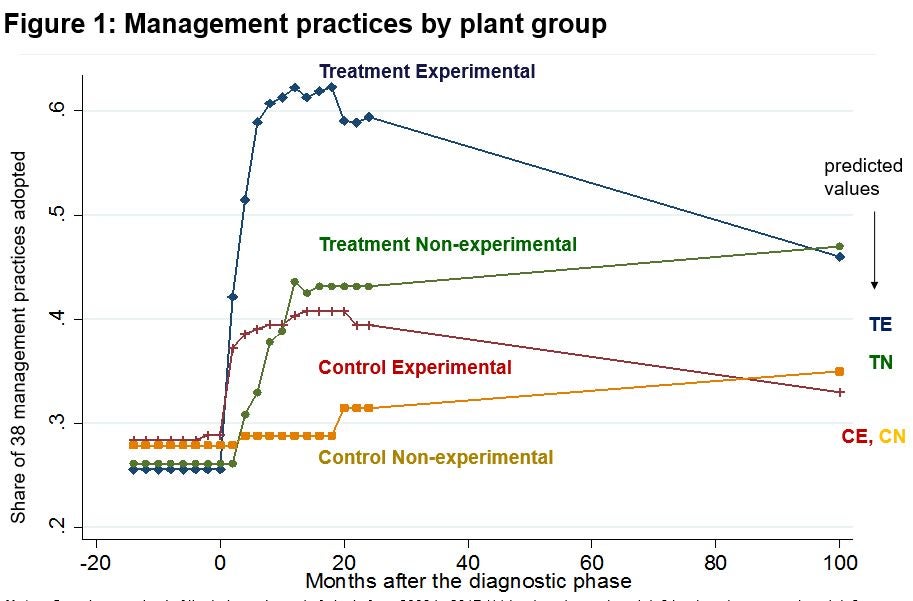

Figure 1 shows what happened to management practices. We find something in between the two views noted above – treated firms did drop about 40% of their original gain in management practices, but the control firms also dropped a lot of the practices they had adopted as a result of receiving the diagnostic. The result is that there is still a large, persistent, and statistically significant 19.7 percentage point gap in the management practices between treatment and control plants 8-9 years later.

These firms typically had two plants. The experimental plants were where the intervention took place, and then in the other plant (labeled non-experimental) we just measured management practices without carrying out a diagnostic or intervention. A second result is that, over time, the level of management practices converges within firms – we see this occurring for both the treated firms, and for the control firms. That is, firms were able to transfer across management practices from one of their plants to another. We measured 38 different practices, and see this convergence also occurs at the individual practice level – the mix of practices used in the experimental plants has a correlation of 0.91 with those used in the non-experimental plants.

Before we collected this data, our research team and the members of the original consulting team set out our priors of what we thought we would find. These are shown by the letters TE (where we expected the treated experimental plants to be), TN, CE and CN at the right of Figure 1. So there was more persistence in management practices than we anticipated.

What stuck, what was dropped, and what did it mean for performance?

We measured practice by practice the reason a management practice was adopted or dropped in a plant. The main reason for dropping practices in the experimental plants was the introduction of a new plant manager, and a second reason was lack of director time. Dropping practices because firms thought they had negative value was only the third most important reason.

We see two types of practices that were most frequently dropped. The first were a set of visual displays and written procedures that very few firms were using before the intervention. The second were a few practices that required a lot of daily attention from management, such as updating visual aids on a daily basis and a type of daily meeting. Conversely, many of these practices are very sticky. These include some practices adopted by 10 or more plants and then never dropped by any of them. They relate very closely to the most immediate improvements in quality and inventory levels that we saw from the original consulting intervention: recording quality defects in a systematic manner (defect-wise); having a system for monitoring and disposing old stock; and carrying out preventative maintenance.

This persistent improvement in management practices does translate into long-run higher labor productivity. We find treated firms have a rising number of looms per employee over time, and we estimate a long-run 35 percent improvement in labor productivity. Revealed preference also suggests firms found the intervention useful – treated firms were significantly more likely to have hired consultants on their own since the intervention, and have also developed better marketing practices to complement the operations-related practices that our intervention focused on.

A few notes on long-term impact evaluation

We are now starting to reach a decade or so since the first wave of RCTs took off, leading to exciting opportunities for researchers to see what happened long after their original study window. Recently we’ve seen long-run papers on de-worming, Progresa, and vocational training as examples. Since experiments on firms took a little longer to start happening, we are only now starting to see people going back. I thought it worth noting a few issues that can arise, and how they were dealt with in our case:

- Firm death: my recent paper shows that when you look at small firms in developing countries, half of those alive today will be dead in 5-6 years, and 40-80% in 10 years. Long-term work therefore runs the risk of having few firms to study. Part of the solution with micros is therefore to track what happens to the owner after the firm dies, and consider outcomes beyond the original firm. But then you need to work really hard to track movement. But in our case, the firms were large (average 270 employees) and old (average of 20 years) to start with. We were therefore fortunate that all firms could still be found – one was in the process of shutting down after the death of the owner, but we could still get some basic data from it.

- Attrition: as well as firm death, long-term studies suffer from attrition if the original respondents can not be found, or are no longer interested in participating. Our sample is small, so this was a particular concern, but we were able to get all firms to agree to be re-interviewed. Using the same consulting company partners and project manager as we had earlier here helped we think, since it was a familiar face to the firm owners.

- Funding: a big challenge for researchers seeking to look at long-term impacts is raising funding to do this. At the World Bank, a lot of funding for impact evaluation is tied to the project cycle, so once the project is over, there is no funding for looking longer-term. As countries like India get richer, the country may no longer be eligible for outside research grants that it would have been eligible at the time of the intervention itself. Yet while there are risks of attrition, I would argue more funders should be looking to fund long-term impact studies. The biggest risk – of whether or not the program will get implemented in a way that can be rigorously evaluated has already been overcome, and many cost-benefit calculations of the return on these programs depend heavily on how long impacts last. In our case we are very grateful to the flexibility provided by a grant from the World Bank’s Strategic Research Program, along with funding from SEED at Stanford for allowing this work to happen.

Join the Conversation