Some of us often try to understand how households may be functioning by using intrahousehold decision making questions. For example, the multi country Demographic and Health Surveys often ask who makes decisions on large household purchase: the male, the female or the two together. The idea is that this kind of question helps us understand power dynamics. And there is a fair bit of correlational work that suggests this makes sense.

Unpacking what this might be measuring is a topic for another post, but for today, a fascinating new paper by Tanguy Bernard, Cheryl Doss, Melissa Hidrobo, Jessical Hoel, and Caitlin Kieran, takes us one step further to show us that the roles people take within the household (as well as who participates in a decision) matter a lot for real outcomes.

So what do I mean by roles in the household? It’s the why behind taking a decision. So if a wife decided what crop to plant, is it because she is in charge? Do village norms dictate that she makes this decision? Or that she is just the best informed person? This is the measurement innovation that Bernard and co. bring to the table. Bernard and co. set out to capture these roles through a series of vignettes, which lay out the following types:

So Bernard and co. are working with around 500 Fulani herders in Senegal (who are cattle farmers). Prior to asking about the vignettes, Bernard and co. ask more standard decision making questions. In particular, they ask who makes decisions about distributing food concentrate among lactating cows (to get at production) and who makes decisions on how to spend the income from the sale of milk (to get at consumption). Once they have the answer to this, this primes the vignettes – so if the wife replies that she alone decides how to spend the money from milk sales, then each vignette will be framed around a woman making this decision (with different motivations/roles as described above).

It’s fairly complicated, but this is a neat innovation. By asking people to identify with (invented) third party stories, it helps tease out the behavior that approximates what the respondent thinks is going on. Before getting to the results, Bernard and co. provide a range of tests to check whether the vignettes are picking up signal or just annoyed noise.

First, they look at whether enumerator characteristics could be driving the response. There seems to be some stuff going on here – male enumerators tend to get more folks identifying with the dictator vignette and community norms for production and more dictators for consumption.

Second, they take a stab at looking at whether they can tease out anything about the reliability of respondents. Here they compare the age and gender correlations with vignette responses to those on the more standard “who decides” questions. Overall, they find little to perturb things.

Finally, Bernard and co. look at potential anchoring effects. To do this they randomize the order of some questions – asking production before consumption and vice versa, as well as asking half of the respondents which type of household they admire before asking them to identify themselves among the vignettes. Here again, there is a bit going on with identification with the dictator vignette higher in the production decisions when the production precedes consumption and higher incidence of the most informed for consumption. The admiration anchoring also seems to distort things a bit.

These are neat data checks and not overly hard to implement. The effects Bernard and co. find aren’t large, but they do point to caution in survey design and maybe checking these things. One open question is whether more normative-leaning questions (like household decision making processes) are more prone to these kind of distortions versus normatively simpler questions (e.g. firm profit).

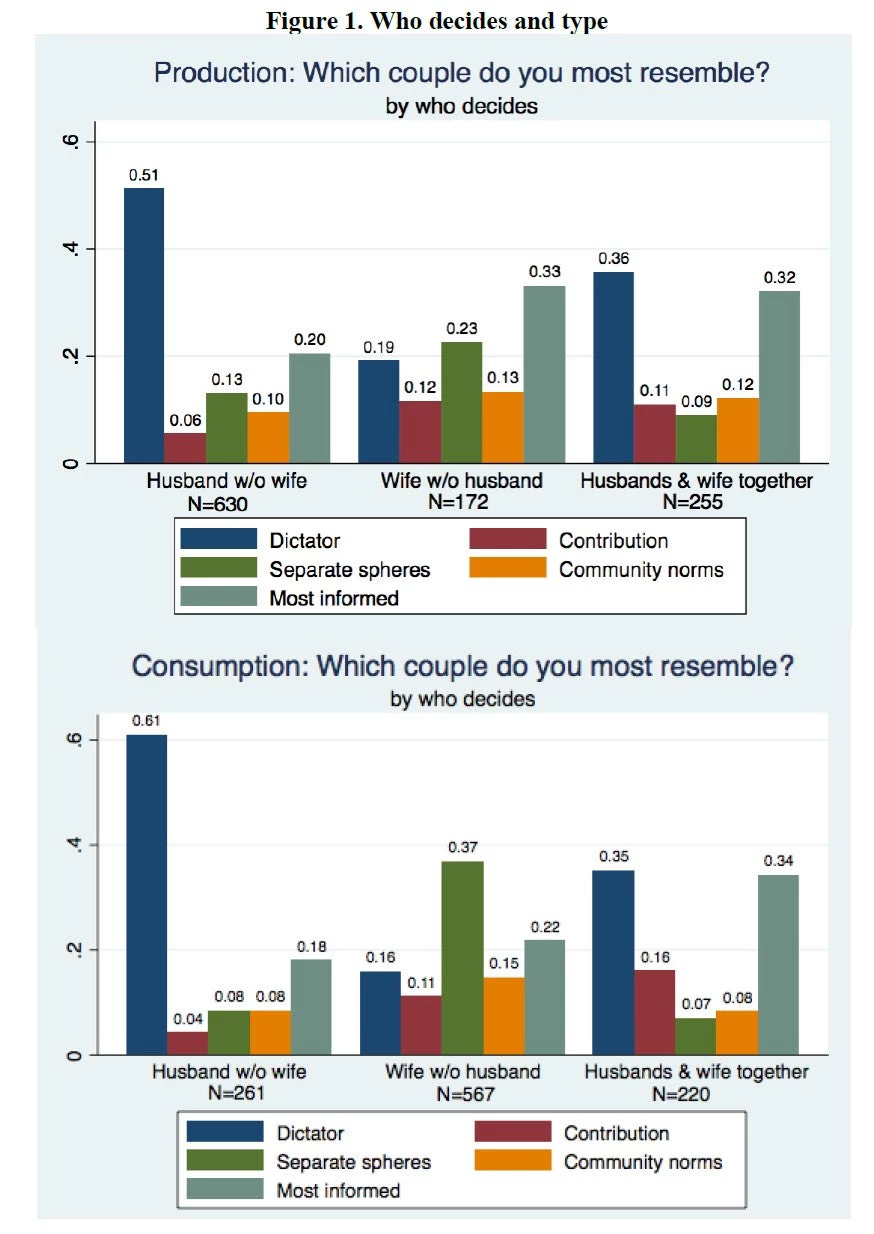

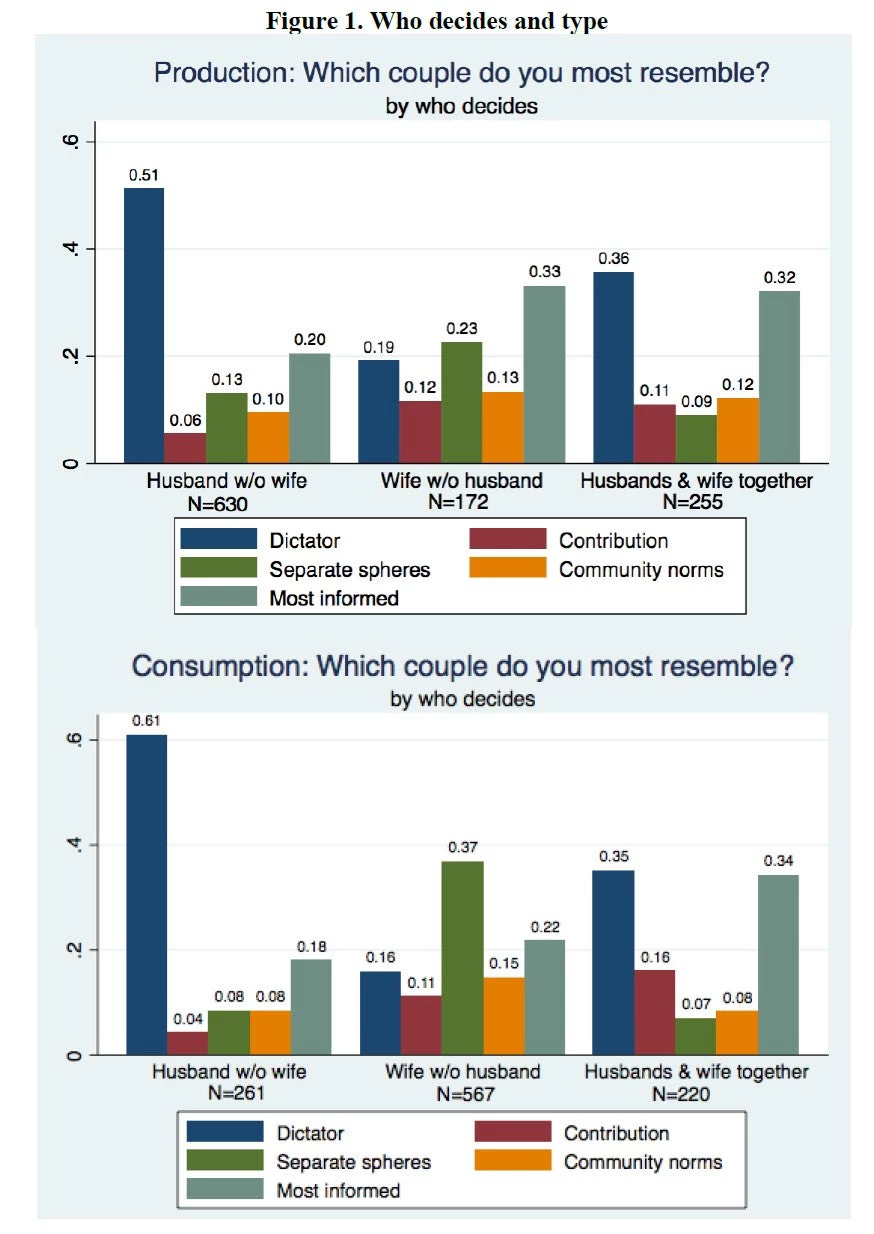

OK, so that’s the measurement tool and its accuracy. What do people say? Figure 1 (from their paper) shows the distribution of responses.

As you can see, when the husband is the main decision maker, there is high identification with the dictator vignette for both production and consumption decisions. When the wife is the sole decision maker, there is a high incidence of most informed for production and separate spheres for consumption.

Now, does this stuff matter for “hard” outcomes? Since this is part of an impact evaluation survey, Bernard and co. turn to milk production (as a production outcome) and child hemoglobin (as a consumption measure). They start out by looking at the simple decision making questions. The main result is that when the husband and wife decide together, child hemoglobin is significantly lower (not a good thing) than when the husband decides alone. Since it looks like the wife deciding alone has the same pattern, one is left with the impression that maybe its better if parents don’t decide together. But before you stop talking to your spouse remember that this is a paper about complicating those measures.

Next Bernard and co. run the types of households against the production and consumption outcomes. In production, relative to the dictator type, the norm driven type of household is associated with significantly lower milk production in the household, while the most informed type is associated with significantly more production. In consumption, relative to the dictator type, the contribution, norms and most informed identifying households all are associated with better outcomes.

Finally, Bernard and co. run the interaction of the two measures. Here we get some further insight into the earlier results. So on the consumption side, the lower child outcomes are driven by joint decision making in couples who act as dictators (somehow together). And on production, the solo wife decision making associated with lower output is driven by wives who identify with the dictator or following norms vignettes.

OK, this is all very complicated. The main things I took away from this were: a) it’s not just about who makes a decision, but also the structure that determines why they can make that decision and b) as in other areas of measuring complex relational things, the vignettes approach seems to have promise – here it is picking up interesting correlations with meaningful consumption and production outcomes.

Unpacking what this might be measuring is a topic for another post, but for today, a fascinating new paper by Tanguy Bernard, Cheryl Doss, Melissa Hidrobo, Jessical Hoel, and Caitlin Kieran, takes us one step further to show us that the roles people take within the household (as well as who participates in a decision) matter a lot for real outcomes.

So what do I mean by roles in the household? It’s the why behind taking a decision. So if a wife decided what crop to plant, is it because she is in charge? Do village norms dictate that she makes this decision? Or that she is just the best informed person? This is the measurement innovation that Bernard and co. bring to the table. Bernard and co. set out to capture these roles through a series of vignettes, which lay out the following types:

- The dictator. S/he makes all the decisions because s/he is in charge. (note: joint dictatorship is an option)

- Contribution. Here the person is the decider because they bring the resources to the table (or farm).

- Separate spheres. She decides everything in one domain, he in an another.

- Norms. That’s the way it is done in this community

- Most informed. The decider is the decider because s/he has the most information.

So Bernard and co. are working with around 500 Fulani herders in Senegal (who are cattle farmers). Prior to asking about the vignettes, Bernard and co. ask more standard decision making questions. In particular, they ask who makes decisions about distributing food concentrate among lactating cows (to get at production) and who makes decisions on how to spend the income from the sale of milk (to get at consumption). Once they have the answer to this, this primes the vignettes – so if the wife replies that she alone decides how to spend the money from milk sales, then each vignette will be framed around a woman making this decision (with different motivations/roles as described above).

It’s fairly complicated, but this is a neat innovation. By asking people to identify with (invented) third party stories, it helps tease out the behavior that approximates what the respondent thinks is going on. Before getting to the results, Bernard and co. provide a range of tests to check whether the vignettes are picking up signal or just annoyed noise.

First, they look at whether enumerator characteristics could be driving the response. There seems to be some stuff going on here – male enumerators tend to get more folks identifying with the dictator vignette and community norms for production and more dictators for consumption.

Second, they take a stab at looking at whether they can tease out anything about the reliability of respondents. Here they compare the age and gender correlations with vignette responses to those on the more standard “who decides” questions. Overall, they find little to perturb things.

Finally, Bernard and co. look at potential anchoring effects. To do this they randomize the order of some questions – asking production before consumption and vice versa, as well as asking half of the respondents which type of household they admire before asking them to identify themselves among the vignettes. Here again, there is a bit going on with identification with the dictator vignette higher in the production decisions when the production precedes consumption and higher incidence of the most informed for consumption. The admiration anchoring also seems to distort things a bit.

These are neat data checks and not overly hard to implement. The effects Bernard and co. find aren’t large, but they do point to caution in survey design and maybe checking these things. One open question is whether more normative-leaning questions (like household decision making processes) are more prone to these kind of distortions versus normatively simpler questions (e.g. firm profit).

OK, so that’s the measurement tool and its accuracy. What do people say? Figure 1 (from their paper) shows the distribution of responses.

As you can see, when the husband is the main decision maker, there is high identification with the dictator vignette for both production and consumption decisions. When the wife is the sole decision maker, there is a high incidence of most informed for production and separate spheres for consumption.

Now, does this stuff matter for “hard” outcomes? Since this is part of an impact evaluation survey, Bernard and co. turn to milk production (as a production outcome) and child hemoglobin (as a consumption measure). They start out by looking at the simple decision making questions. The main result is that when the husband and wife decide together, child hemoglobin is significantly lower (not a good thing) than when the husband decides alone. Since it looks like the wife deciding alone has the same pattern, one is left with the impression that maybe its better if parents don’t decide together. But before you stop talking to your spouse remember that this is a paper about complicating those measures.

Next Bernard and co. run the types of households against the production and consumption outcomes. In production, relative to the dictator type, the norm driven type of household is associated with significantly lower milk production in the household, while the most informed type is associated with significantly more production. In consumption, relative to the dictator type, the contribution, norms and most informed identifying households all are associated with better outcomes.

Finally, Bernard and co. run the interaction of the two measures. Here we get some further insight into the earlier results. So on the consumption side, the lower child outcomes are driven by joint decision making in couples who act as dictators (somehow together). And on production, the solo wife decision making associated with lower output is driven by wives who identify with the dictator or following norms vignettes.

OK, this is all very complicated. The main things I took away from this were: a) it’s not just about who makes a decision, but also the structure that determines why they can make that decision and b) as in other areas of measuring complex relational things, the vignettes approach seems to have promise – here it is picking up interesting correlations with meaningful consumption and production outcomes.

Join the Conversation