Youth employment is a significant and pressing development issue. But it’s not clear what governments can do. There have been several metareviews of active labor market policies, including a recent

one by David, and they’re fairly depressing – showing not much impact at all. Into this fray, however, comes a new

paper by Livia Alfonsi, Oriana Bandiera, Vittorio Bassi, Robin Burgess, Imran Rasul, Munshi Sulaiman, and Anna Vitali. And it offers some hope.

Alfonsi and co. have designed an epic experiment. The idea is not only to look at the impact of vocational training versus apprenticeships, but also to tackle the firm side by looking at matching. There are a host of treatment groups. The basics are six months of vocational training (VT) versus a six-month subsidy for firms to do in-house training (FT) or apprenticeships. Potential workers are randomized across these treatments. Crossed with this is matching, where potential receiving firms are randomized in to being matched with VT workers, wage subsidy (FT) workers, just plain untrained workers. Working through the NGO BRAC, Alfonsi and co. restrict these interventions to eight (fairly large) sectors.

The setting is Uganda. Uganda has a lot of youth (60% of the population is under 20), and a large fraction of them are unemployed (over 60% in the Alfonsi and co. sample). Alfonsi and co. collect a host of data, not only surveying 1741 workers over four years, but also testing these workers on things like occupation-specific skills. And they survey the firms too.

On the worker side, take-up of the program is good. Eighty percent of those offered vocational training take it, and 95 percent of those complete it (they picked good training institutions and incentivized them to retain students). On the matching there is less joy (as is to be expected in the labor market): when offered workers with a wage subsidy (the FT group), firms offered jobs to 45 percent of them, but this is 12 percent in the VT plus matching group and 17 percent in the just plain matching group. But it wasn’t love at first sight for the workers either: In the wage subsidy group 75 percent of them took the jobs, but this around 25 percent for the others.

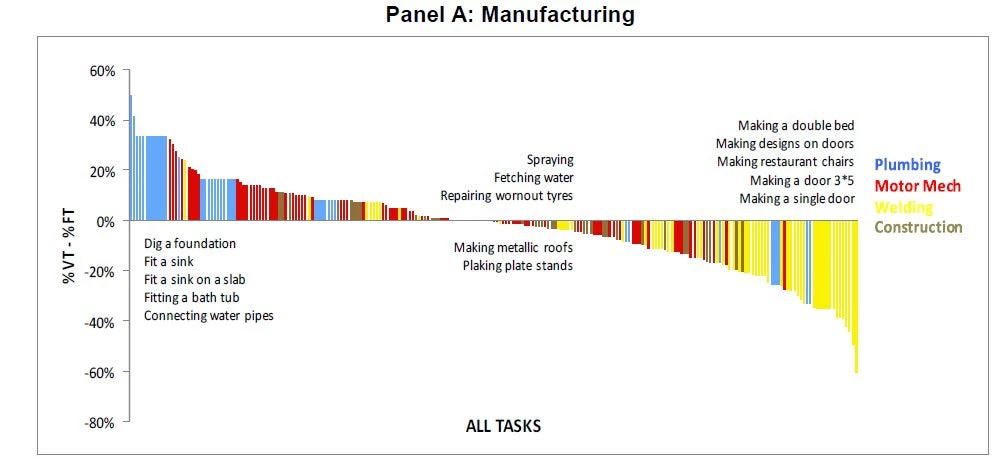

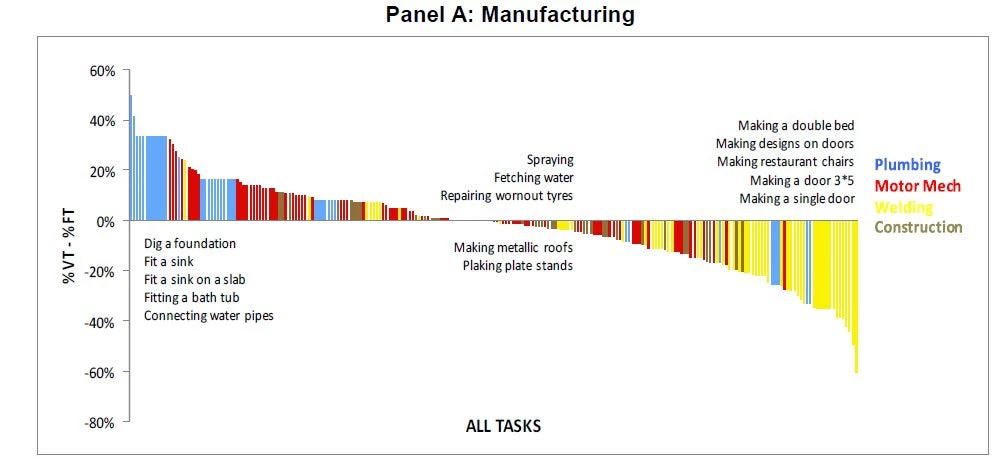

When a worker completes vocational training, they get a certificate. This is important because this certificate is something that one can show to potential employers. On the other hand, on-the-job training doesn’t come with a certificate and it’s much harder to signal. It’s also likely to have different content. And indeed, this is what Alfonsi and co find. They look at the different tasks that the VT and FT groups perform, and as you can see from their wonderfully colorful figure below, there is a marked difference across the groups (in this case for manufacturing).

Working with local occupational skills assessors, Alfonsi and co. actually test the workers on skills relevant to their sector. Strikingly, only the VT group shows significantly higher skills than the control group. The on-the-job training the FT group is getting is quite firm specific training (Indeed, Alfonsi and co. confirm this with a direct question to the workers about the transferability of their skills.

Now, do they actually get jobs? Both the FT and VT groups are about 7 percentage points more likely to be in wage employment (this is about 26% more than the control group). In addition, the VT group is about 4 percentage points more likely (relative to the control) to be in self employment (the results are not significant for the FT group). One other interesting result in this vein is that a fair fraction of the FT group is actually retained in the firm they were matched to, well after the wage subsidy has ended.

Once on the job, these workers work more. VT workers on average 1.1 months more, which is (significantly) more than their FT counterparts and 25% more than the control group. And they also work more hours.

Wages are also higher. FT workers translate their on-the-job training to hourly wages that are 61% higher than the control group, and VT workers see their wages rise by 52%. Putting this together with the increased labor supply mean that FT workers earn 22% more than the control group, and VT workers earn 40% more.

So this gives us the first puzzle. Why don’t workers pay for this type of training? Alfonsi and co. check whether this is due to workers not having good information on the effects of training. Their information may actually not be good, but it goes in the wrong direction, with workers systematically over optimistic about the returns to training. So Alfonsi and co. chalk this up to credit constraints: the baseline earnings are quite low and credit markets are incomplete, so this could be why folks aren’t buying the training for themselves.

To try and unpack the mechanisms behind these impacts, Alfonsi and co. estimate a structural model of the job ladder. This lets them look at unemployment to job transitions versus job to job transitions. What the results show is that not only do VT workers have higher transitions from unemployment to a job, they also have higher job to job transitions. They are getting more offers when already on the job and taking those jobs when the wages are higher. So they’re pulling away from the FT workers who are stuck at the firm that has trained them.

Taking a deeper look at the firm side, Alfonsi and co. give us two key results. First, when looking at who chooses to match with workers, Alfonsi and co. find that the firms that are interested in the wage subsidized workers have significantly lower profits per worker. So part of the lower returns to FT may in fact be driven by the fact that these folks are getting matched with lower profit firms.

Their second firm level result looks at employment displacement. One concern with these types of interventions is that the trained workers just elbow out the untrained folks. Alfonsi and co. set up the design of the experiment to limit this at the market level – matching only 8 workers in each sector-region market, where there is, on average, 156 employed workers and 40 firms. But they can also look within the treated firms. And here, there is again not-so-great news for the FT group. For firms getting a subsidized worker to train there isn’t a significant growth in employment. So these workers are elbowing out potential non-subsidized hires. For the other arms, Alfonsi and co. can’t say anything definitive since workers are retained too infrequently.

A couple of weeks ago, I blogged about some on-the-job training where very little of the productivity gains translated into gains for the workers. In their epic experiment, Alfonsi and co. have some evidence on this as well. It turns out that firms that get a wage subsidy for their worker have 13 percent higher monthly profits. Alfonsi and co. use this, plus some wage estimates (and other stuff) to estimate that 35% of the surplus generated by the wage subsidy goes to the worker.

Finally, Alfonsi and co. do a nice job of look at the internal rate of return and cost benefits. To summarize: the benefit cost ratio is 1.69 for the FT workers and over 4 for VT workers. So not a bad investment.

This is an epic experiment with encouraging results, particularly for the proponents of vocational training. But it’s out of line with the string of evaluations that have come before it. Alfonsi and co. offer a bunch of possible non-exclusive explanations: 1) they focus on only 8 sectors, which not only reduces mismatch, but also (probably) increases their power, 2) the treatments are fairly intensive – six months of training for the VT group and a higher than average wage subsidy, 3) there is low attrition (13 percent), 4) workers who select into the sample are folks who are willing to go through 6 months of training, and 5) they work with vocational training providers selected to be of the best quality. This last potential explanation is worth noting. My general sense of these markets is that there are a fair amount of not-so-great quality training providers. So these results push us to think more about the markets in general and what interventions may get us better providers.

At any rate, this project scores a key point for vocational training. Let’s see what comes next.

Alfonsi and co. have designed an epic experiment. The idea is not only to look at the impact of vocational training versus apprenticeships, but also to tackle the firm side by looking at matching. There are a host of treatment groups. The basics are six months of vocational training (VT) versus a six-month subsidy for firms to do in-house training (FT) or apprenticeships. Potential workers are randomized across these treatments. Crossed with this is matching, where potential receiving firms are randomized in to being matched with VT workers, wage subsidy (FT) workers, just plain untrained workers. Working through the NGO BRAC, Alfonsi and co. restrict these interventions to eight (fairly large) sectors.

The setting is Uganda. Uganda has a lot of youth (60% of the population is under 20), and a large fraction of them are unemployed (over 60% in the Alfonsi and co. sample). Alfonsi and co. collect a host of data, not only surveying 1741 workers over four years, but also testing these workers on things like occupation-specific skills. And they survey the firms too.

On the worker side, take-up of the program is good. Eighty percent of those offered vocational training take it, and 95 percent of those complete it (they picked good training institutions and incentivized them to retain students). On the matching there is less joy (as is to be expected in the labor market): when offered workers with a wage subsidy (the FT group), firms offered jobs to 45 percent of them, but this is 12 percent in the VT plus matching group and 17 percent in the just plain matching group. But it wasn’t love at first sight for the workers either: In the wage subsidy group 75 percent of them took the jobs, but this around 25 percent for the others.

When a worker completes vocational training, they get a certificate. This is important because this certificate is something that one can show to potential employers. On the other hand, on-the-job training doesn’t come with a certificate and it’s much harder to signal. It’s also likely to have different content. And indeed, this is what Alfonsi and co find. They look at the different tasks that the VT and FT groups perform, and as you can see from their wonderfully colorful figure below, there is a marked difference across the groups (in this case for manufacturing).

Working with local occupational skills assessors, Alfonsi and co. actually test the workers on skills relevant to their sector. Strikingly, only the VT group shows significantly higher skills than the control group. The on-the-job training the FT group is getting is quite firm specific training (Indeed, Alfonsi and co. confirm this with a direct question to the workers about the transferability of their skills.

Now, do they actually get jobs? Both the FT and VT groups are about 7 percentage points more likely to be in wage employment (this is about 26% more than the control group). In addition, the VT group is about 4 percentage points more likely (relative to the control) to be in self employment (the results are not significant for the FT group). One other interesting result in this vein is that a fair fraction of the FT group is actually retained in the firm they were matched to, well after the wage subsidy has ended.

Once on the job, these workers work more. VT workers on average 1.1 months more, which is (significantly) more than their FT counterparts and 25% more than the control group. And they also work more hours.

Wages are also higher. FT workers translate their on-the-job training to hourly wages that are 61% higher than the control group, and VT workers see their wages rise by 52%. Putting this together with the increased labor supply mean that FT workers earn 22% more than the control group, and VT workers earn 40% more.

So this gives us the first puzzle. Why don’t workers pay for this type of training? Alfonsi and co. check whether this is due to workers not having good information on the effects of training. Their information may actually not be good, but it goes in the wrong direction, with workers systematically over optimistic about the returns to training. So Alfonsi and co. chalk this up to credit constraints: the baseline earnings are quite low and credit markets are incomplete, so this could be why folks aren’t buying the training for themselves.

To try and unpack the mechanisms behind these impacts, Alfonsi and co. estimate a structural model of the job ladder. This lets them look at unemployment to job transitions versus job to job transitions. What the results show is that not only do VT workers have higher transitions from unemployment to a job, they also have higher job to job transitions. They are getting more offers when already on the job and taking those jobs when the wages are higher. So they’re pulling away from the FT workers who are stuck at the firm that has trained them.

Taking a deeper look at the firm side, Alfonsi and co. give us two key results. First, when looking at who chooses to match with workers, Alfonsi and co. find that the firms that are interested in the wage subsidized workers have significantly lower profits per worker. So part of the lower returns to FT may in fact be driven by the fact that these folks are getting matched with lower profit firms.

Their second firm level result looks at employment displacement. One concern with these types of interventions is that the trained workers just elbow out the untrained folks. Alfonsi and co. set up the design of the experiment to limit this at the market level – matching only 8 workers in each sector-region market, where there is, on average, 156 employed workers and 40 firms. But they can also look within the treated firms. And here, there is again not-so-great news for the FT group. For firms getting a subsidized worker to train there isn’t a significant growth in employment. So these workers are elbowing out potential non-subsidized hires. For the other arms, Alfonsi and co. can’t say anything definitive since workers are retained too infrequently.

A couple of weeks ago, I blogged about some on-the-job training where very little of the productivity gains translated into gains for the workers. In their epic experiment, Alfonsi and co. have some evidence on this as well. It turns out that firms that get a wage subsidy for their worker have 13 percent higher monthly profits. Alfonsi and co. use this, plus some wage estimates (and other stuff) to estimate that 35% of the surplus generated by the wage subsidy goes to the worker.

Finally, Alfonsi and co. do a nice job of look at the internal rate of return and cost benefits. To summarize: the benefit cost ratio is 1.69 for the FT workers and over 4 for VT workers. So not a bad investment.

This is an epic experiment with encouraging results, particularly for the proponents of vocational training. But it’s out of line with the string of evaluations that have come before it. Alfonsi and co. offer a bunch of possible non-exclusive explanations: 1) they focus on only 8 sectors, which not only reduces mismatch, but also (probably) increases their power, 2) the treatments are fairly intensive – six months of training for the VT group and a higher than average wage subsidy, 3) there is low attrition (13 percent), 4) workers who select into the sample are folks who are willing to go through 6 months of training, and 5) they work with vocational training providers selected to be of the best quality. This last potential explanation is worth noting. My general sense of these markets is that there are a fair amount of not-so-great quality training providers. So these results push us to think more about the markets in general and what interventions may get us better providers.

At any rate, this project scores a key point for vocational training. Let’s see what comes next.

Join the Conversation