“There is nothing in this book that needs to be confirmed by complex laboratory experiments. You have only to open the window or step into the street”, Hernando de Soto, The Other Path, p14., 1989.

Hernando de Soto famously argued that informality is costly for firms, and that informal firms would desperately like to formalize, but are hampered in doing so by the maze of red tape and complicated regulations they must go through in order to be formal. The result has been the influential Doing Business agenda, which has made it easier for firms to start businesses around the world. Certainly such efforts have been welcome to many people seeking to start a business, with data from both macro and micro studies suggested more formal firms are created when entry is easier. But is this enough to get most informal firms to formalize?

I have a new paper with Suresh de Mel and Chris Woodruff which tries to experimentally measure the demand for formalization among informal firms in Sri Lanka, and then measure the consequences of formalizing on these firms. We took a sample of 520 informal firms around Kandy and Colombo, and randomly allocated them to the following groups:

· Control group

· Information and free cost group: provided information about how to register, along with reimbursement for the small cost of registering

· Information + money: groups were given information on how to register, plus incentives of 10,000, 20,000 and 40,000 Sri Lankan Rupees (approximately US$88, $175 and $350 respectively) to register.

A new 2-page Finance & PSD Impact note summarizes the results here, along with some discussion of policy implications. I’ll highlight some key results, and then focus on a couple of issues for impact evaluation.

Main results

· Information and paying the registration cost had no impact on registration. 17-22 percent of eligible firms register when offered 10,000 or 20,000 LKR, just under half a month’s and one month’s profits for the median firm respectively, and 48 percent register when offered 40,000 LKR.

· Three rounds of follow-up surveys at 15, 22 and 31 months after the start of the intervention were taken in order to measure what impact, if any, formalizing was having on the firms. We find increases in mean profits, which appears to come from the upper tail, with most firms not experiencing a profits increase; we find little evidence for most of the channels through which proponents of formalization claim it benefits firms – firms were no more likely to obtain credit, participate in government programs, or get government contracts. However, we do find formalizing led to firms doing more advertising, keeping receipt books, and having more trust in local government.

Interesting things for impact evaluation

1) Sampling informal firms:

One obvious thing about informal firms is that you won’t find them on any standard firm list, making coming up with a sample frame challenging. Our solution was to draw geographic blocks, and then do full listings within these blocks to come up with a sample. One concern you might have is whether firms are willing or not to admit they are informal. We actually experienced the opposite problem, with some firms saying they were informal at baseline, only for us to discover later that they were really formal, or at least quasi-formal (with the registration in perhaps their father’s name, or for a different location, etc.). In a follow-up survey we gave firms small incentives to prove their formality status, by e.g. paying them for showing us their business registration certificate – something it would have been good to have thought of at baseline.

2) Action at a tail – how do we know it is genuine?

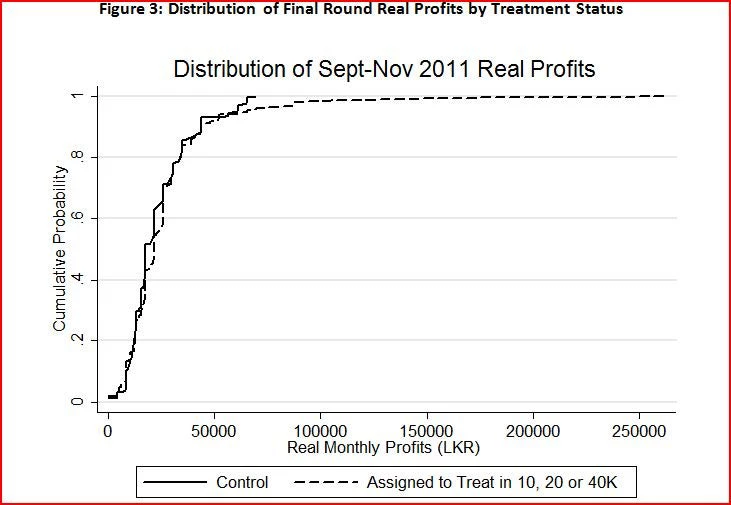

Here is a plot of the CDFs of final round profits for the treatment and control groups. You see that the distributions look very similar to one another write up to about the 90th or 95th percentile, and then there are a few treatment firms that had much higher final round profits than the control firms. This is what leads to a significant treatment effect on mean profits, but as soon as we truncate profits this impact falls and becomes insignificant.

The obvious question is then whether these few firms driving the results represent genuine change, or just measurement error. To address this issue we went to each firm with large changes in profits and conducted case studies to see whether this change seemed genuine. Although small in number, these more detailed case studies provide support for the idea that a few firms had benefited substantially from formalizing. For example, two of the firms were in the vehicle repair business—one automobiles and one autorickshaws. Both said that an important consequence of registration was the ability to become an official parts distributor for an auto parts manufacturer. Previously, they had purchased parts from another dealer, i.e., at higher than the wholesale price. Both had also undertaken expansions of the physical facilities, with one adding an auto lift and a customer waiting room, while increasing employment from 2 to 8 workers. A saw mill which registered said the key was to be able to put the forest service stamp on the receipts which he issued. The stamp allows customers to transport the wood across municipal boundaries without obtaining further permissions. His estimate was that he had previously lost 25 percent of sales to other mills which could provide this stamp. Finally, a grocery store and tea (snack) shop had used the license to obtain a loan to purchase a delivery truck. The truck was used in the business, but also leased out. On his own, he had gone to the health department to request a health inspection for his tea shop. He was intent on improving his score so that he would obtain a health sticker he could display, and so that he could open a bakery and wholesale bread.

These types of cases of rapid firm growth are rare – and perhaps put us in the world of studies of rare diseases where initial studies identify some effect, and then follow-up trials try and explore this effect more by either having massive samples, or screening to get a sample of at-risk individuals. The problem with doing this with firms is that it is much harder to identify ex ante which firms are at-risk of potential fast growth – something several ongoing studies are looking at.

3) When no effect is a result

One response we have received to the paper is that it is disappointing it finds only limited effects on economic outcomes or mediating channels – and that the paper would perhaps have better publication prospects if we found large effects. However, as the CDF above shows, on profits we not only find not much effect for the average firm, but we have pretty good data to show this; while for mediating channels many of the zero effects we find are quite precise zeros. This then raises the issue of publication bias. We think in our case the fact that there don’t seem to be large positive effects of formalizing on most firms that formalize is an interesting result.

Join the Conversation