There are roughly 781 million illiterate adults in the world (and that’s probably an underestimate), according to

UNESCO. Yet we know vanishingly little about how to reduce adult illiteracy. From a look at citations in recent papers and a quick search, I find 7 studies that estimate the impact of adult literacy programs on adult literacy in the last 25 years: One in

Kenya (1990), one in

Venezuela (2008), one in

Ghana in 2005, and another in

Ghana in 2011 (

ungated), one in

Niger (2015), and one in

India (2015). There is

one more from Niger that compares two alternative modes of delivering adult education, but without a pure control group (2012). Of those 7, the latter three (Niger, Niger, and India) are randomized controlled trials, two more use regression analysis, and two others present simple summary statistics (either a simple before-after, or a comparison with a comparison group identified ex post).

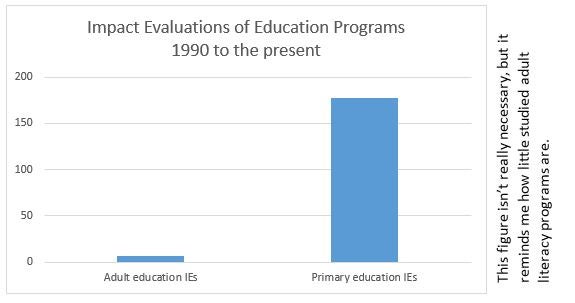

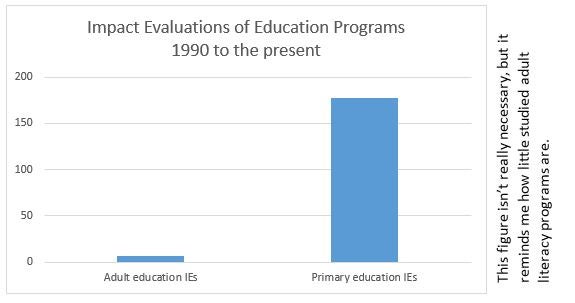

Compare that with the 177 studies on the effectiveness of learning interventions in primary education that Popova and I recently identified (and that number has grown since). There’s so little evidence that adult literacy doesn’t even merit inclusion in 3ie’s Education Evidence Gap Map, which targets only primary and secondary interventions. The whole field is an ocean of gaps with 7 islets of evidence.

A few weeks ago, I summarized the 2015 paper from Niger by Aker & Ksoll.

Here, I summarize the 2015 paper from India, by Banerji, Berry, and Shotland.

The Intervention and the Design

The program consisted of three treatments:

Sorry, it’s just not that kind of hamlet

Intermediate Results

Take up of the literacy classes was relatively low. 7% of mothers in the control group attended literacy classes, 39% of mothers in the Mother Literacy group attended at least once, and 44% of mothers in the combined group attended at least once. A significant proportion of children attended the ML classes with their mothers (27% in the ML group). Because CHAMP consisted of home visits, take up was much higher for that element: The authors estimate that 90% of households were visited at least once, and the average households was visited 20 times.

Impacts

Mothers’ learning rose significantly in all three groups, even using the intent-to-treat estimator and despite low take-up. For language, test scores rose 0.06 standard deviations in the ML group, 0.02 in the CHAMP group, and 0.09 in the ML+CHAMP group. Math increases were higher, at 0.12 for the ML group and 0.15 for the ML+CHAMP group. Treatment-on-the-treated estimates for the ML group were – as one would expect from the take-up – almost three times higher, and – as one wouldn’t necessarily expect – strongly significant.

A composite measure of women’s empowerment rose in all three groups, with a weakly significant increase in the ML group and a strongly significant increase in the ML+CHAMP group.

Child learning rose in math in all three groups in the ITT estimates: 0.04 standard deviations in the ML group and the CHAMP group, and 0.06 in the ML+CHAMP group. For math, the TOT estimates remain significant. For language, the combined intervention had an impact but not either of the others.

In terms of mechanisms, there is evidence in all three groups that mothers are more involved in children’s learning (more likely to talk to the child about school and look at their school notebook in all the interventions, and more likely to help with homework in the CHAMP and ML+CHAMP interventions). Likewise, there is some increase in actual home education assets for both CHAMP and ML+CHAMP.

Sad Scale-up Realities

Unfortunately, the jump from NGO to government implementation proved tricky. During the study, the government of one state adopted the program materials and hired teachers for the Mother Literacy program. “Based on observations by our field staff, the implementation was a failure. Very few classes were set up, and of those, the vast majority ran for only a few days.” It sounds like the scale-up of contract teachers redux.

What is the Return to Adult Education?

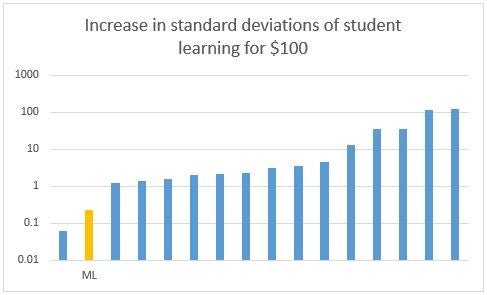

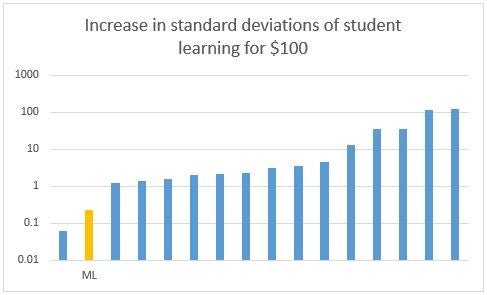

The authors laudably carry out a cost-effectiveness analysis. Of course, cost-effectiveness analysis only works with one outcome: How much of an increase in X does $100 get you? They choose child learning, as previous work by Kremer et al. (2013) provides 15 comparator studies. Adult education, in this context, is less cost effective than 14 of them. The only less cost effective program is a cash transfer program in Malawi. So if your only goal is children’s learning outcomes and you have to choose between cash transfers and an adult literacy program, then take the adult literacy program!

The 3ie gap map is available

here.

The 3ie gap map is available

here.

This blog post is the second in a series linked to the background research for an ongoing Africa Regional Study on Skills, led by Omar Arias and me.

(The photo is of Edwin Booth as Hamlet, circa 1870. It is in the public domain.)

Compare that with the 177 studies on the effectiveness of learning interventions in primary education that Popova and I recently identified (and that number has grown since). There’s so little evidence that adult literacy doesn’t even merit inclusion in 3ie’s Education Evidence Gap Map, which targets only primary and secondary interventions. The whole field is an ocean of gaps with 7 islets of evidence.

A few weeks ago, I summarized the 2015 paper from Niger by Aker & Ksoll.

Here, I summarize the 2015 paper from India, by Banerji, Berry, and Shotland.

The Intervention and the Design

The program consisted of three treatments:

- Mother Literacy (ML): Daily literacy classes for non-literate mothers. Two hours a day, six days a week. Trained volunteers taught the classes. The curriculum included both language and math, with more emphasis on math in response to expressed demand from mothers.

- Child and Mother Activities Packet (CHAMP): A paid staff member of the implementing NGO, Pratham, visited each mother once a week, gave her a worksheet that she could help her child to complete, and instructed her on how to get more involved in her child’s learning. The visits lasted about 15-20 minutes.

- Combined ML + CHAMP: Both interventions, implemented as they were in the other villages (i.e., volunteers providing ML and paid employees providing CHAMP).

Sorry, it’s just not that kind of hamlet

Intermediate Results

Take up of the literacy classes was relatively low. 7% of mothers in the control group attended literacy classes, 39% of mothers in the Mother Literacy group attended at least once, and 44% of mothers in the combined group attended at least once. A significant proportion of children attended the ML classes with their mothers (27% in the ML group). Because CHAMP consisted of home visits, take up was much higher for that element: The authors estimate that 90% of households were visited at least once, and the average households was visited 20 times.

Impacts

Mothers’ learning rose significantly in all three groups, even using the intent-to-treat estimator and despite low take-up. For language, test scores rose 0.06 standard deviations in the ML group, 0.02 in the CHAMP group, and 0.09 in the ML+CHAMP group. Math increases were higher, at 0.12 for the ML group and 0.15 for the ML+CHAMP group. Treatment-on-the-treated estimates for the ML group were – as one would expect from the take-up – almost three times higher, and – as one wouldn’t necessarily expect – strongly significant.

A composite measure of women’s empowerment rose in all three groups, with a weakly significant increase in the ML group and a strongly significant increase in the ML+CHAMP group.

Child learning rose in math in all three groups in the ITT estimates: 0.04 standard deviations in the ML group and the CHAMP group, and 0.06 in the ML+CHAMP group. For math, the TOT estimates remain significant. For language, the combined intervention had an impact but not either of the others.

In terms of mechanisms, there is evidence in all three groups that mothers are more involved in children’s learning (more likely to talk to the child about school and look at their school notebook in all the interventions, and more likely to help with homework in the CHAMP and ML+CHAMP interventions). Likewise, there is some increase in actual home education assets for both CHAMP and ML+CHAMP.

Sad Scale-up Realities

Unfortunately, the jump from NGO to government implementation proved tricky. During the study, the government of one state adopted the program materials and hired teachers for the Mother Literacy program. “Based on observations by our field staff, the implementation was a failure. Very few classes were set up, and of those, the vast majority ran for only a few days.” It sounds like the scale-up of contract teachers redux.

What is the Return to Adult Education?

The authors laudably carry out a cost-effectiveness analysis. Of course, cost-effectiveness analysis only works with one outcome: How much of an increase in X does $100 get you? They choose child learning, as previous work by Kremer et al. (2013) provides 15 comparator studies. Adult education, in this context, is less cost effective than 14 of them. The only less cost effective program is a cash transfer program in Malawi. So if your only goal is children’s learning outcomes and you have to choose between cash transfers and an adult literacy program, then take the adult literacy program!

My figure, based on

JPAL cost-effectiveness data for 15 programs

The authors reasonably argue that, because this program has multiple outcomes, a single-outcome cost-effectiveness analysis doesn’t make sense. That’s where a cost-benefit analysis comes in. But in order to do that, one would have to quantify the returns to – among other things – increased mother literacy. In rural agricultural communities – for example – what are the returns to improved literacy likely to be? Evidence on this is scarce. One study, by

Blunch and Pörtner (2011), uses instrumental variables (IV) estimation to suggest that adult literacy programs in Ghana increase consumption, partly because households are “more likely to engage in market activities and to sell a variety of agricultural goods.” While that’s just one IV study, it is consistent with the positive impact on empowerment identified in the India study we’ve been discussing.

If we can bring together more evidence on the returns to adult education, we might find the seed of an idea for increasing take-up. We have evidence from Madagascar (

Nguyen 2008) and the Dominican Republic (

Jensen 2010) that providing accurate information on the returns to schooling to youth can improve test scores and reduce dropout. In the India adult education study, qualitative interviews revealed one key reason for not attending the Mother Literacy program was “a perception that there was little value in attending.” If that’s not true, than it may be worth experimenting with an intervention to change that perception.

If you're interested in evaluating an adult literacy program, you can use my preliminary gap map to guide where we really need big questions answered...

If you're interested in evaluating an adult literacy program, you can use my preliminary gap map to guide where we really need big questions answered...

This blog post is the second in a series linked to the background research for an ongoing Africa Regional Study on Skills, led by Omar Arias and me.

(The photo is of Edwin Booth as Hamlet, circa 1870. It is in the public domain.)

Join the Conversation