This is the fifth in our series of guest posts by graduates on the job market this year.

Commitment is popular. Contrary to standard neoclassical predictions, the last decade has seen a surge of evidence documenting a demand for (self-)commitment contracts – roughly understood as a voluntary restriction of one's future choice set, in order to overcome intrapersonal conflicts. Applications are as broad as the scope of human ambition, and range from gym memberships, diet clubs and pension savings to taking only a fixed amount of cash (and no credit cards) when going shopping, and putting one's alarm clock at the other side of the room (for a humorous illustration, see the money-shredding alarm clock). In the context of developing countries, documented demand for commitment devices goes back to the literature on rotating savings and credit organisations (ROSCAs), the wandering deposit collectors of South Asia and Africa, and more recent studies on newly introduced commitment savings products (see Ashraf et al. (2006), Brune et al. (2011) and Dupas and Robinson (2013)).

My job market paper provides evidence that commitment can be harmful if agents select into a commitment contract that is ill-suited for their preferences – and that they frequently do. By construction, correctly choosing a welfare-improving contract requires knowledge about one's future preferences, including possible biases and inconsistencies: To determine whether a contract will enable an agent to follow through with a plan, the agent needs to anticipate how his future selves will behave under the contract. Consequently, if the agent is overconfident, or imperfectly informed about his own future preferences, the contract may result in undesirable behaviour, and the agent may be hurt, rather than helped. Given that the very nature of most commitment contracts is to impose penalties (usually of a monetary or social nature) for undesirable behaviour, adopting a commitment device that is ill-suited to one's preferences may 'backfire' and become a threat to welfare (as an example, consider signing up to an expensive gym membership to commit yourself to exercise, and then not going anyway, see DellaVigna and Malmendier (2006)). I show that failed commitment may be a serious concern in developing country interventions intended to reduce poverty.

Experiment Design

In a sample of 913 individuals from a low-income population in the Philippines (obtained through door-to-door marketing), I conducted a randomised controlled trial where individuals were randomly offered a new commitment savings account with a (customizable) fixed regular instalment plan. In addition to the choice of a goal amount, a goal date, and a weekly instalment plan, clients could choose the `stakes' of the commitment contract themselves: If they fell three or more deposits behind on their savings plan, their account was closed, and a default penalty was charged. The default penalty was chosen by the client upon contract-signing, and framed as a charity donation. To control for marketing effects, the entire sample received a non-binding personal savings plan for an upcoming expenditure, as well as a free non-commitment savings account with 100 pesos (U.S. $ 2.50). Durations of savings plans varied on an individual level, but were limited between three and six months. The effect of offering the regular-instalment commitment product was compared to a) a control group who only received the marketing treatment and b) a control group who was offered a pure withdrawal-restriction commitment product (identical to that in Ashraf et al. (2006)), which allowed individuals to restrict withdrawals of their savings before either a date goal or an amount goal had been reached.

Results

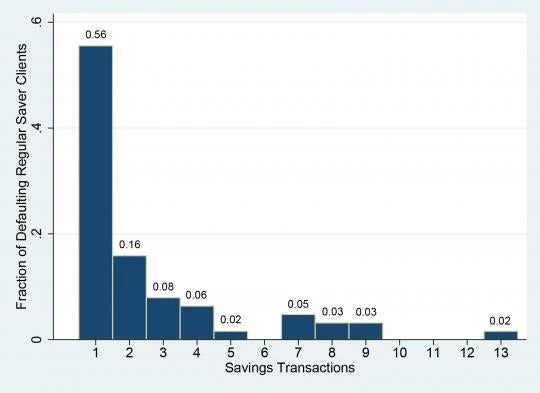

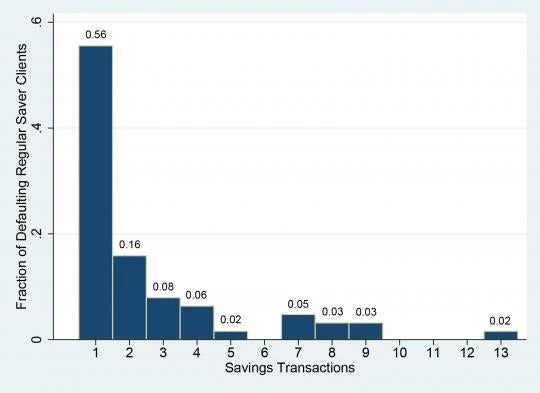

I find that the average effect (intent-to-treat) on bank savings is large and significant: Offering the regular-instalment product increased bank savings by U.S. $14 (27 percent of median weekly household income) after 4.5 months, whereas offering the withdrawal-restriction product increased savings by U.S. $3.50 (7 percent). However, this average treatment effect hides substantial heterogeneity: 55 percent of regular-instalment clients default on their savings contract, and incur the associated penalty (typically about a day’s income). It appears that the median client chooses a commitment contract which ends up harming him. What happened? Two possibilities emerge:

The second possibility requires a deviation from rational expectations: Mistakes (choices that are not optimal under rational expectations) can happen if individuals have incorrect beliefs about their future preferences or their income distribution. The paper presents a model of partially sophisticated time-inconsistent agents – i.e., agents who are more impatient over current trade-offs than over future trade-offs (and thus likely to procrastinate unpleasant activities like saving), but who are only partially aware of this bias. Such agents are likely to select into a commitment contract that is too ‘weak’ – the penalty for non-compliance is too low to enforce the desired behaviour, resulting in costly default. Looking at the data, it is notable that 80 percent of individuals chose the minimum permissible termination fee for their savings goal ($3.50 or $6). Did individuals underestimate the amount of commitment it would take to make them save?

Using measures of both observed and self-perceived time-inconsistency, I find that individuals’ perception of their own inconsistency significantly predicts take-up of the regular-instalment commitment product: Relatively ‘naïve’ agents select in, while relatively ‘sophisticated’ agents stay away. A possible interpretation is that sophisticates realize that a low penalty will not be effective for them (while a high penalty may be undesirable in an uncertain environment). Conditional on take-up, sophisticated agents are less likely to default – possibly because they chose more incentive-compatible contracts. Consistent with a story of under-commitment, measures of actual time-inconsistency (irrespective of individual’s awareness of it) do not predict take-up, but they do predict default. Other explanations discussed in the paper include income optimism, limited attention, and aggregate shocks.

The welfare risks suggested in this study are not singular – a closer look at heterogeneity behind average treatment effects in the literature reveals that adverse effects of commitment products may be widespread: The paper is closest in spirit to DellaVigna and Malmendier (2006) who show that U.S. consumers choose gym contracts which are cost-inefficient given their attendance frequency. In a savings context, Ashraf et al. (2006) find that a withdrawal-restriction product increased savings on average, but 50 percent of the 202 clients made no further deposits after the opening balance. For clients with an amount goal, this implies that their initial savings may be tied up indefinitely. Finally, 66 percent of the smokers who accepted the savings contract offered in Giné et al. (2010) failed to quit smoking and lost their savings as a result.

Summing up, research on new commitment products should carefully consider possible risks to welfare – and look beyond positive average treatment effects in assessing them.

Anett Hofmann is a PhD Candidate at the London School of Economics, and a member of STICERD. Her primary research interests are Development Economics and Behavioural Economics. Anett is on the academic job market this year.

Commitment is popular. Contrary to standard neoclassical predictions, the last decade has seen a surge of evidence documenting a demand for (self-)commitment contracts – roughly understood as a voluntary restriction of one's future choice set, in order to overcome intrapersonal conflicts. Applications are as broad as the scope of human ambition, and range from gym memberships, diet clubs and pension savings to taking only a fixed amount of cash (and no credit cards) when going shopping, and putting one's alarm clock at the other side of the room (for a humorous illustration, see the money-shredding alarm clock). In the context of developing countries, documented demand for commitment devices goes back to the literature on rotating savings and credit organisations (ROSCAs), the wandering deposit collectors of South Asia and Africa, and more recent studies on newly introduced commitment savings products (see Ashraf et al. (2006), Brune et al. (2011) and Dupas and Robinson (2013)).

My job market paper provides evidence that commitment can be harmful if agents select into a commitment contract that is ill-suited for their preferences – and that they frequently do. By construction, correctly choosing a welfare-improving contract requires knowledge about one's future preferences, including possible biases and inconsistencies: To determine whether a contract will enable an agent to follow through with a plan, the agent needs to anticipate how his future selves will behave under the contract. Consequently, if the agent is overconfident, or imperfectly informed about his own future preferences, the contract may result in undesirable behaviour, and the agent may be hurt, rather than helped. Given that the very nature of most commitment contracts is to impose penalties (usually of a monetary or social nature) for undesirable behaviour, adopting a commitment device that is ill-suited to one's preferences may 'backfire' and become a threat to welfare (as an example, consider signing up to an expensive gym membership to commit yourself to exercise, and then not going anyway, see DellaVigna and Malmendier (2006)). I show that failed commitment may be a serious concern in developing country interventions intended to reduce poverty.

Experiment Design

In a sample of 913 individuals from a low-income population in the Philippines (obtained through door-to-door marketing), I conducted a randomised controlled trial where individuals were randomly offered a new commitment savings account with a (customizable) fixed regular instalment plan. In addition to the choice of a goal amount, a goal date, and a weekly instalment plan, clients could choose the `stakes' of the commitment contract themselves: If they fell three or more deposits behind on their savings plan, their account was closed, and a default penalty was charged. The default penalty was chosen by the client upon contract-signing, and framed as a charity donation. To control for marketing effects, the entire sample received a non-binding personal savings plan for an upcoming expenditure, as well as a free non-commitment savings account with 100 pesos (U.S. $ 2.50). Durations of savings plans varied on an individual level, but were limited between three and six months. The effect of offering the regular-instalment commitment product was compared to a) a control group who only received the marketing treatment and b) a control group who was offered a pure withdrawal-restriction commitment product (identical to that in Ashraf et al. (2006)), which allowed individuals to restrict withdrawals of their savings before either a date goal or an amount goal had been reached.

Results

I find that the average effect (intent-to-treat) on bank savings is large and significant: Offering the regular-instalment product increased bank savings by U.S. $14 (27 percent of median weekly household income) after 4.5 months, whereas offering the withdrawal-restriction product increased savings by U.S. $3.50 (7 percent). However, this average treatment effect hides substantial heterogeneity: 55 percent of regular-instalment clients default on their savings contract, and incur the associated penalty (typically about a day’s income). It appears that the median client chooses a commitment contract which ends up harming him. What happened? Two possibilities emerge:

- Clients had chosen a regular-instalment contract which was optimal for them in expectation, and then rationally defaulted upon observing a shock (such as loss of job, an unexpected hospital bill, or a shock to long-run preferences) – in other words, a `bad luck' scenario.

- Clients chose the contract by mistake.

The second possibility requires a deviation from rational expectations: Mistakes (choices that are not optimal under rational expectations) can happen if individuals have incorrect beliefs about their future preferences or their income distribution. The paper presents a model of partially sophisticated time-inconsistent agents – i.e., agents who are more impatient over current trade-offs than over future trade-offs (and thus likely to procrastinate unpleasant activities like saving), but who are only partially aware of this bias. Such agents are likely to select into a commitment contract that is too ‘weak’ – the penalty for non-compliance is too low to enforce the desired behaviour, resulting in costly default. Looking at the data, it is notable that 80 percent of individuals chose the minimum permissible termination fee for their savings goal ($3.50 or $6). Did individuals underestimate the amount of commitment it would take to make them save?

Using measures of both observed and self-perceived time-inconsistency, I find that individuals’ perception of their own inconsistency significantly predicts take-up of the regular-instalment commitment product: Relatively ‘naïve’ agents select in, while relatively ‘sophisticated’ agents stay away. A possible interpretation is that sophisticates realize that a low penalty will not be effective for them (while a high penalty may be undesirable in an uncertain environment). Conditional on take-up, sophisticated agents are less likely to default – possibly because they chose more incentive-compatible contracts. Consistent with a story of under-commitment, measures of actual time-inconsistency (irrespective of individual’s awareness of it) do not predict take-up, but they do predict default. Other explanations discussed in the paper include income optimism, limited attention, and aggregate shocks.

The welfare risks suggested in this study are not singular – a closer look at heterogeneity behind average treatment effects in the literature reveals that adverse effects of commitment products may be widespread: The paper is closest in spirit to DellaVigna and Malmendier (2006) who show that U.S. consumers choose gym contracts which are cost-inefficient given their attendance frequency. In a savings context, Ashraf et al. (2006) find that a withdrawal-restriction product increased savings on average, but 50 percent of the 202 clients made no further deposits after the opening balance. For clients with an amount goal, this implies that their initial savings may be tied up indefinitely. Finally, 66 percent of the smokers who accepted the savings contract offered in Giné et al. (2010) failed to quit smoking and lost their savings as a result.

Summing up, research on new commitment products should carefully consider possible risks to welfare – and look beyond positive average treatment effects in assessing them.

Anett Hofmann is a PhD Candidate at the London School of Economics, and a member of STICERD. Her primary research interests are Development Economics and Behavioural Economics. Anett is on the academic job market this year.

Join the Conversation