Administrative tax data are great for so many different reasons: you can study taxpayer responses to tax policy reform (most obviously! see

Pomeranz & Vila-Belda (forthcoming), and

Slemrod 2017 for reviews), but also non-tax questions, for instance related to

intergenerational mobility,

firm production networks, or

who becomes an inventor, to just name a few. For practitioners in development organizations, tax data can help prepare technical assistance and investment projects, or monitor their implementation.

This blog collects some thoughts on how to get started in working with tax admin data. First, it provides a primer on what tax data is, describing the different types of tax data, modes of accessing tax data and briefly reviewing the main upsides and downsides of working with tax data. Second, I discuss some practical advice on the logistics, from building a first contact with the tax authority (TA) to pitching a project and formulating a data request. This draws on my PhD research and experience at the World Bank, where I work with tax data from various countries, including on a new pilot project between different World Bank units (the Macro, Trade and Investment Global Practice, the Research Department and the Global Tax Team) which investigates what can be learned from comparing micro tax data across countries.

For a more detailed discussion of tax data, see this guidance note, and for insights from a survey with 70 researchers working with administrative tax data, see Pomeranz & Vila-Belda (forthcoming).

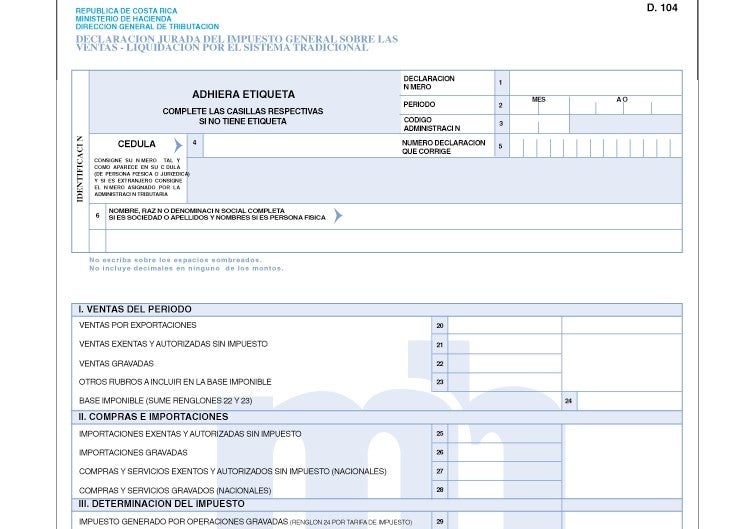

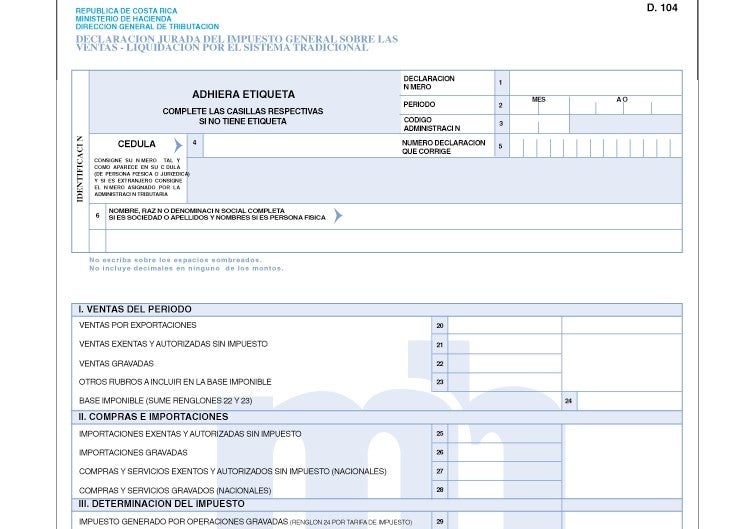

Figure 1: Costa Rica’s VAT declaration form

Data can be analyzed in Stata or R, but given the potential unavailability of STATA at government offices and the free availability of R, junior researchers should probably invest in R.

Upsides

In terms of capacity building, local ownership and quality of the project (and potentially also ease of accessing data), it can be a good idea to identify not just a local champion but an actual co-author ( Juliana Londoño-Vélez and Pierre Bachas have fared very well with this).

It would then detail the data needed:

Once the data has been accessed, it is important to maintain a regular exchange with the TA, communicate intermediate results, seek feedback and consult on the final dissemination strategy and policy discussion surrounding the results. After all, improving policy design – either directly or indirectly, by improving our knowledge – should be the key objective of the analysis.

This blog collects some thoughts on how to get started in working with tax admin data. First, it provides a primer on what tax data is, describing the different types of tax data, modes of accessing tax data and briefly reviewing the main upsides and downsides of working with tax data. Second, I discuss some practical advice on the logistics, from building a first contact with the tax authority (TA) to pitching a project and formulating a data request. This draws on my PhD research and experience at the World Bank, where I work with tax data from various countries, including on a new pilot project between different World Bank units (the Macro, Trade and Investment Global Practice, the Research Department and the Global Tax Team) which investigates what can be learned from comparing micro tax data across countries.

For a more detailed discussion of tax data, see this guidance note, and for insights from a survey with 70 researchers working with administrative tax data, see Pomeranz & Vila-Belda (forthcoming).

Types of tax data

What do we mean by administrative tax data? Tax data are collected by the TA in the process of exercising its functions – collecting government revenue. There are five broad categories of tax data (for an illustration with data from Costa Rica, see the data sections in Brockmeyer et al 2019 and Brockmeyer & Hernandez 2018).- Tax Register: the list of all registered taxpayers at a point in time, with the unique identifier, name, geographic location, and (for firms) sector and legal form;

- Taxpayer self-assessment declarations: declarations that taxpayers submit themselves (e.g. firms submit corporate income tax and VAT declarations (e.g. Figure 1 below for Costa Rica), individuals may submit personal income tax declarations);

- Informative declarations and withholding declarations: forms submitted to the TA by third parties that report on taxpayers’ taxable transactions (e.g. firms report purchases from other firms, credit card companies report retailers’ card sales, procurement agencies report firms’ sales to the government); these data are often at the transaction-level; they are used for tax compliance purposes;

- Customs data: transaction-level records of imports and exports, should be shared with the TA (but unfortunately that’s not always the case);

- Process and HR data: records of TA internal processes, e.g. audits; spell data on work history, remuneration and bonuses of TA employees;

Figure 1: Costa Rica’s VAT declaration form

Modes of accessing tax data

Different countries provide access to their tax data in different ways. From least to most restrictive, these are the options I have encountered:- The data is available online (believe it or not, some Scandinavian countries actually publish identified tax data; Mexico publishes de-identified data).

- The TA extracts and hands over the data to specific individuals/institutions under a Memorandum of Understanding (this is how researchers work with data from Senegal and Pakistan).

- The TA extracts de-identified data for specific institutions under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), requiring that the data be considered confidential, with restricted access in a secure computer outside of the TA premises but regulated by a data security plan which, among other provisions, requires that the computer is not connect to the internet (e.g. some state governments in Brazil have provided data access this way).

- The TA provides remote access to the data to selected/screened individuals via a secure server (this is theoretically possible, but I have not seen an example).

- The TA provides access to the data onsite (e.g. at the Datalab at the UK TA (HMRC)). In this case, external partners can either work onsite or work with a TA staff who runs do-files/scripts.

Data can be analyzed in Stata or R, but given the potential unavailability of STATA at government offices and the free availability of R, junior researchers should probably invest in R.

Upsides and downsides of tax data

It is good to be mindful of a few characteristics of tax data when preparing to work with them.Upsides

- Tax data contain the universe of the formal sector. Unlike survey data, they are less prone to selective non-reporting at the top of the income distribution. Unlike census data, they contain more detailed information, and are collected at high frequency.

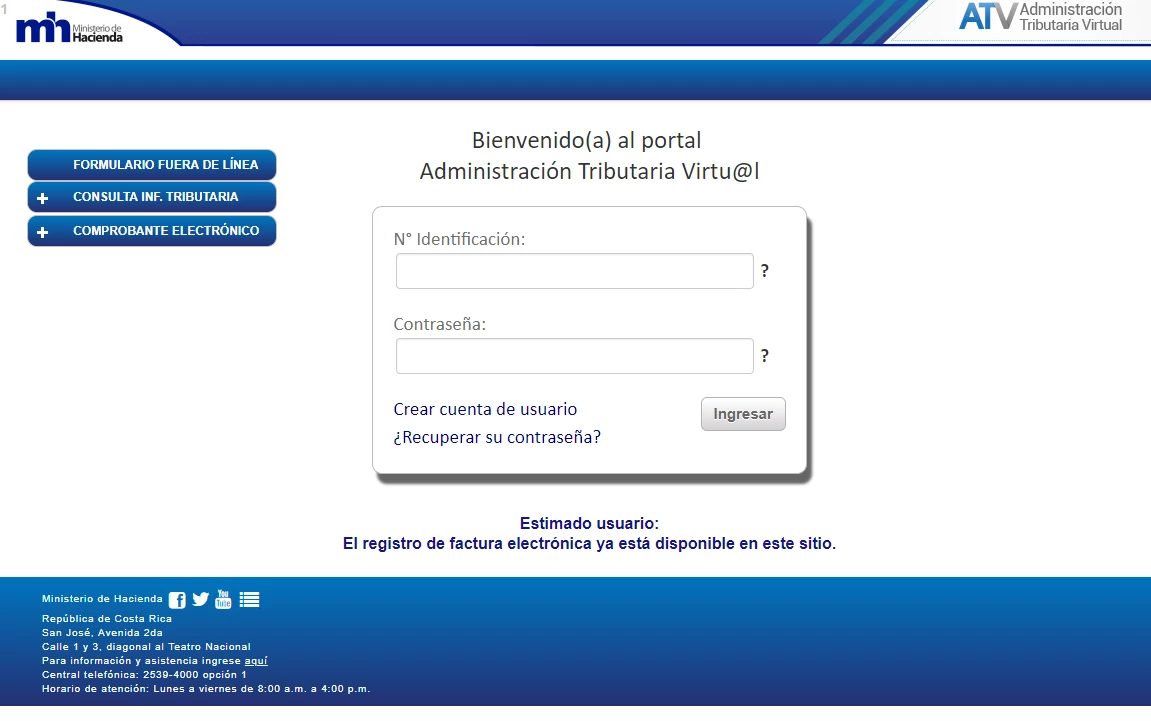

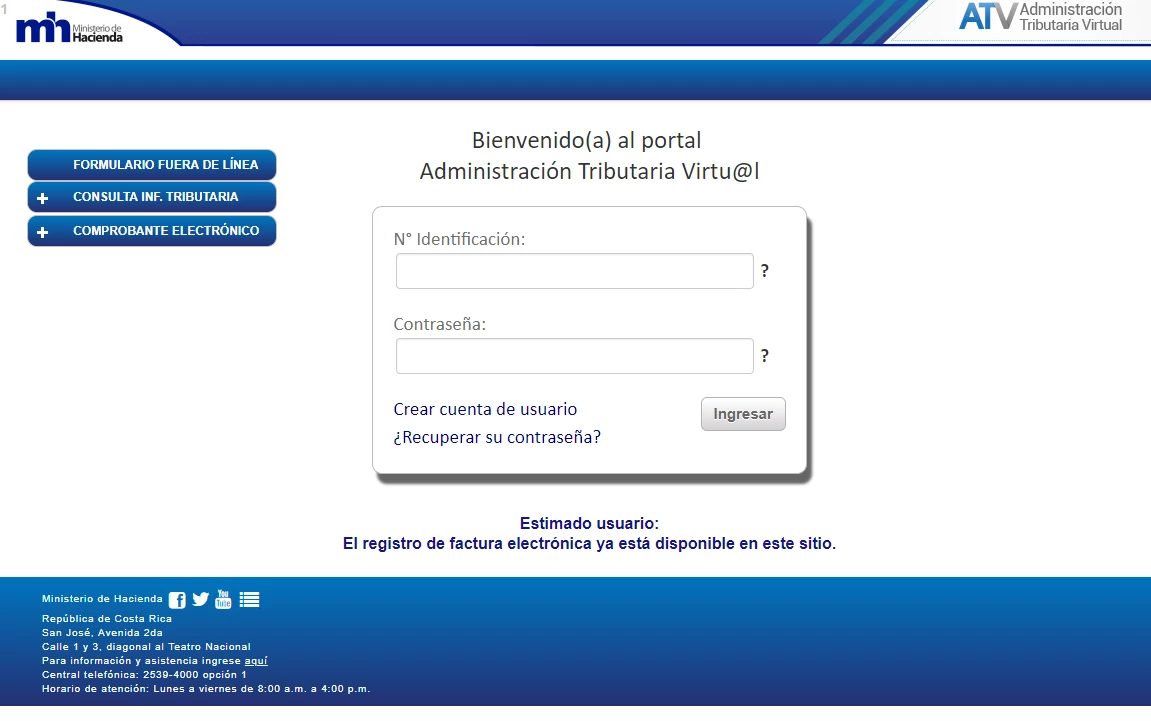

- Most types of tax data are now collected electronically, which minimizes errors (e.g. Figure 2 below, which shows the online tax filing portal for Costa Rica).

- As the data is the product of actual economic processes, it measures variables with high precision, unlike survey data in which respondents provide ballpark figures as their response has no consequence for themselves.

- The fact that the data is directly economically relevant for those people who provide the data (mostly taxpayers or their transaction partners) also means that the data is not necessarily good in capturing real economic outcomes. Self-assessment declarations in particular capture reported outcomes. Informative declarations are more likely to capture real outcomes, as the reporting agent has less incentive to misreport and is often more tightly monitored.

- Tax data can be poor on demographic information on individuals and households unless they can be merged with other government data (studies in Denmark and Sweden have exploited the ability to merge across various types of administrative data).

- Lots of documentation is available to understand tax data (tax returns, tax laws and decrees that explain the tax system), but unlike survey/census data, tax data is not collected for primarily analytical purposes, and is thus not accompanied by researcher-friendly codebooks. Understanding the data requires knowledge of the relevant language and a regular exchange with the TA.

Building a connection with the tax authority

Once a research (policy) question that requires access to tax data is identified, some diplomacy and entrepreneurial spirit is usually necessary to make the project happen. Here are some practical steps, primarily for junior researchers.- Find a context/country that you know well or have some connection to, ideally one that is not yet over-researched, so as to avoid overlap with other research teams.

- Identify a contact person or local champion in the TA (great if someone senior who has the TA’s trust can introduce you).

- Spend time to understand

- the country’s tax system, its particularities, and policy challenges [read World Bank and IMF reports, the country’s tax laws, reports by the TA, and above all, talk to people];

- the data structure (here, I mean to try to understand the tax return forms and other data formats – postpone direct discussions about the data for a bit);

- then link a+b to the broader question you want to study, derive a more specific formulation of the question and hypothesis, and flesh out your methodological approach (quasi-experiment/RCT/structural).

- After many “learning meetings” and some informal discussions about the project, pitch your project to your government counterpart. Then continue the dialogue by integrating feedback, adjusting your project to fit realities on the ground and policy needs, and, if needed, re-pitch your project until you have buy-in. Then start discussing the data request and associated logistics (you might have touched on this topic previously in an informal way).

- Obviously, the key ingredient for a successful project pitch is a policy-relevant project which allows the government to improve on or learn something they would otherwise not be able to achieve, and which is in line with their mandate and actual policy challenges. In addition, it can help to weave into your pitch some of the following: evidence that other countries provide access to their tax data for research (ideally “aspirational” peers = slightly more developed countries); examples of the policy impact of projects using tax data; evidence of your own track record using tax admin data/policy impact, if applicable.

In terms of capacity building, local ownership and quality of the project (and potentially also ease of accessing data), it can be a good idea to identify not just a local champion but an actual co-author ( Juliana Londoño-Vélez and Pierre Bachas have fared very well with this).

Formulating a data request

Once the government counterparts have agreed to the project, a formal data request can be prepared. It would reiterate the (agreed upon) purpose of the data use, the benefits of the study, and specify the mode of data access (or propose further discussions on this).It would then detail the data needed:

- Type of dataset (e.g. annual corporate income tax declarations);

- Sample (e.g. all corporations in all tax offices);

- Period covered;

- Identifiers: unique taxpayer ID (de-identified), tax year, declaration submission date, declaration number;

- Variables: list the line items/boxes on the tax return that are needed (if the tax return isn’t too long, it’s often easiest to request all variables, which makes the request easier to deal with for the person extracting the data, prevents issues due to errors in variable selection, and limits the need for follow-up requests to add variables);

- Any additional variables that need to be merged into the data (e.g. sector codes for all firms from the tax register).

Once the data has been accessed, it is important to maintain a regular exchange with the TA, communicate intermediate results, seek feedback and consult on the final dissemination strategy and policy discussion surrounding the results. After all, improving policy design – either directly or indirectly, by improving our knowledge – should be the key objective of the analysis.

Join the Conversation