I came across a new working paper written by researchers at Google and Microsoft with the title “

on the near impossibility of measuring the returns to advertising”. They begin by noting the astounding statistic that annual US advertising revenue is $173 billion, or about $500 per American per year. That’s right, more than the GDP per capita of countries like Burundi, Madagascar and Eritrea is spent just on advertising!

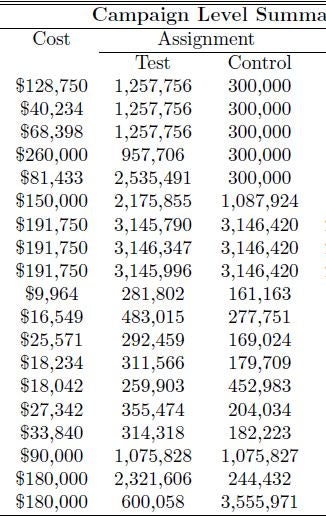

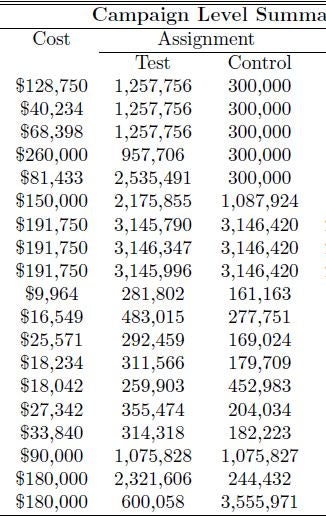

The question they ask is then whether this advertising is worth it. They consider 25 online advertising experiments done by American retailers, totaling $2.8 million, summarized in the table below:

You can see these experiments typically have more than 1 million customers in them. The retailers are able to randomize delivery of the advertisements at the individual level, and link to individual purchase decisions. However, they find:

This came as a surprise to me, after hearing about how large retailers run 1000s of experiments a year (e.g. in my review of Jim Manzi’s book I give an example from his book that Capital One runs more than 60,000 experiments per year) – this new paper is saying that for many firms, when it comes to advertising at least, it is almost impossible for them to know whether it is working or not.

However, it is similar to the problems we face in trying to learn whether government policies to help firms are working or not – basically the problem is that even sizeable effects of policies are small relative to the enormous heterogeneity there is across firms, and volatility that exists in sales and profits for a given firm over time.

I have thought a lot about the implications of this for learning about the effectiveness of policies, but much less about the implications for firms’ abilities to learn about themselves. The same problems with learning the return from advertising are likely to be as much, or even more, of an issue for firms attempting to learn the impact of changes in other business practices they employ. This might help explain why the lack of adoption by many firms of a large number of modern management practices – if firms can’t tell whether they are working or not, even if these practices have incredibly high returns, then it is perhaps no wonder that many firms don’t take up such practices.

This matters, because in the rare cases we do an intervention on firms and find that it works, the immediate response is why firms haven’t done it already/what the market failure is that prevents this occurring without our help? E.g. we find that improving management services has high returns to firms, so the immediate response of some economists is to say “if this really works so well, why aren’t firms improving it of their own accord, or at least the market providing these improvements to firms”. But if it is really hard for a single firm to learn whether any change they make works or not, the scope for learning is much much less. As the authors note, this provides an added advantage to being a really large firm – they can be the only ones with the scale to let this learning take place. It also provides a further role for the types of experimental interventions we are doing – opening up the possibility to learn across firms things that no single firm can learn by itself.

The question they ask is then whether this advertising is worth it. They consider 25 online advertising experiments done by American retailers, totaling $2.8 million, summarized in the table below:

You can see these experiments typically have more than 1 million customers in them. The retailers are able to randomize delivery of the advertisements at the individual level, and link to individual purchase decisions. However, they find:

- Only 10 out of the 25 experiments have sufficient power to detect whether the advertising had any effect at all on consumer behavior.

- Only 3 out of the 25 experiments have sufficient power to be able to distinguish between a 0% return on investment, and a wildly profitable campaign which has a 50% return on investment over 2 weeks!

- The median confidence interval for the return on investment is over 100 percentage points wide.

This came as a surprise to me, after hearing about how large retailers run 1000s of experiments a year (e.g. in my review of Jim Manzi’s book I give an example from his book that Capital One runs more than 60,000 experiments per year) – this new paper is saying that for many firms, when it comes to advertising at least, it is almost impossible for them to know whether it is working or not.

However, it is similar to the problems we face in trying to learn whether government policies to help firms are working or not – basically the problem is that even sizeable effects of policies are small relative to the enormous heterogeneity there is across firms, and volatility that exists in sales and profits for a given firm over time.

I have thought a lot about the implications of this for learning about the effectiveness of policies, but much less about the implications for firms’ abilities to learn about themselves. The same problems with learning the return from advertising are likely to be as much, or even more, of an issue for firms attempting to learn the impact of changes in other business practices they employ. This might help explain why the lack of adoption by many firms of a large number of modern management practices – if firms can’t tell whether they are working or not, even if these practices have incredibly high returns, then it is perhaps no wonder that many firms don’t take up such practices.

This matters, because in the rare cases we do an intervention on firms and find that it works, the immediate response is why firms haven’t done it already/what the market failure is that prevents this occurring without our help? E.g. we find that improving management services has high returns to firms, so the immediate response of some economists is to say “if this really works so well, why aren’t firms improving it of their own accord, or at least the market providing these improvements to firms”. But if it is really hard for a single firm to learn whether any change they make works or not, the scope for learning is much much less. As the authors note, this provides an added advantage to being a really large firm – they can be the only ones with the scale to let this learning take place. It also provides a further role for the types of experimental interventions we are doing – opening up the possibility to learn across firms things that no single firm can learn by itself.

Join the Conversation