A common research question in the migration and development literature is “what is the impact of an individual migrating on other members of their family such as their spouse or children.?”. For example, there are many papers that look at impacts on children’s education, spousal labor supply, or household income. This literature typically considers the family as fixed or predetermined. However, in practice migration changes how families form, dissolve, and are conceptualized, so that migration involves not only different counterfactual outcomes for the migrant, but also potentially different counterfactual families associated with them.

In a new working paper (joint with Simone Bertoli and Elie Murard), we show empirically that changing marital status after migration is widespread, and that the traditional model of a fixed family sending off a migrant who remains part of that same family only describes a minority of migrants moving from developing countries to the U.S. We then discuss what this means for attempts to measure causal impacts of migration on spousal and child outcomes.

Documenting changes in marital status with international migration

Data availability is a big challenge when attempting to look at how family structure changes with migration. There are no long panels which track large numbers of international migrants from their home countries to destinations and then follow them over time. Censuses in destination countries typically ask marital status and place of birth, but it is much rarer to ask year of migration, and rarer still to also have information on year of marriage so that we can tell whether marriage occurred before or after migration.

The American Community Survey (ACS) is one of the few data sources that enable looking at this question. We use the 2017-2021 years of the ACS to document how marital status changes with migration. We focus on individuals currently aged 18 to 60 who migrated from a developing country to the U.S., and moved when they were adults aged 18 to 40. Using questions on year of marriage and year of migration, we can then see whether marriage occurred before, in the same year as, or after migration.

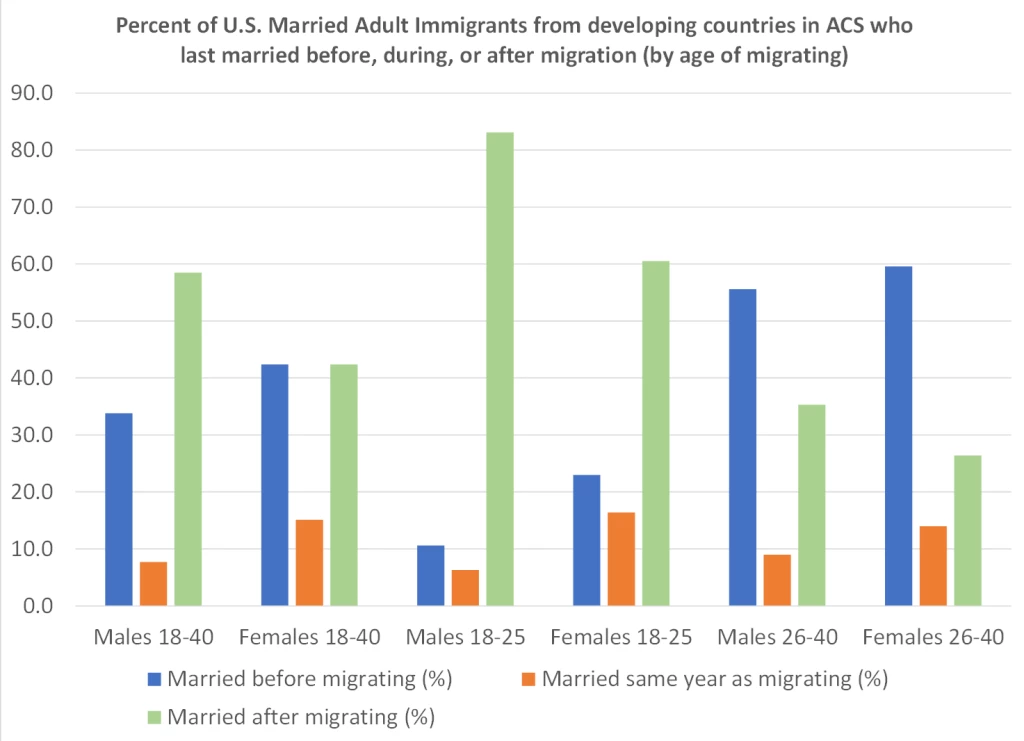

Overall, only 38.5 percent of ever-married adult immigrants were married before migrating, 11.8 percent married in the year of migration, and half (49.8 percent) were married after migrating. Conditional on getting married after migration, the median duration between migration and marriage is 6 years, suggesting that these marriages are from relationships that only were formed after migrating. Figure 1 shows this by gender and age of migration. Individuals who migrate aged 18 to 25, the peak age for migration from developing countries, are especially likely to have married after migration: 83.1 percent of males aged 18 to 40 who migrated when aged 18 to 25 married after migrating. I was 26 when I moved to the U.S., and met and married my wife over here, so am a typical migrant in this regard.

Figure 1: A minority of ever-married adult migrants were married before migrating

The paper looks at how these patterns vary across major origin countries (Mexico, India, China, the Philippines) and the MENA region. Migrants from these different origins differ in their median age of migration and skill level: only 31 percent of Mexican men are married before migrating, compared to 40 percent of Indian and Chinese men, while only 22 percent of Indian migrant women marry after migration.

Migrants may also end up never marrying, divorcing, being widowed, and/or remarrying. The result is that only about one-third of adult immigrants are currently living with a spouse who they married before migration. That is, the typical family structure assumed in most of the literature is in fact the minority family arrangement.

Counterfactual families and their implications

There are therefore substantial changes in marital status after international migration. But moving to a different place does not only affect whether and when you marry, but also who you marry (and also whether and which kids you may end up having). This means each potential destination an individual is considering living in could each come with its own, different, counterfactual family. This has several implications for both the decision to migrate, and for causally measuring migration impacts.

1. Migration decisions can be dynamically and locationally inconsistent

It is common to model migration as a family decision, in which a potential migrant may contract with other family members (for insurance purposes or to fund migration), and in which migration is motivated both by own well-being as well as by the well-being of ones’ spouse and children. One of the costs of migration in these models is the cost of any temporary absence from family members. But if the family is changing with migration, then the people whose utility you care about if you stay at home may be different individuals from those you would care about if you moved to a new country and met a different spouse – and the optimal decision based on the family you have in one location may be different from the optimal decision based on the family you would have in a different location.

2. The inability to picture these counterfactual families may cause a bias towards not migrating

One of the big puzzles in the migration literature is how few people move, despite the enormous income gains to be had from migrating. One reason can be that the costs of leaving behind family and friends are very high. But people typically can’t imagine the family (and friends) they would form should they move to a different location. Failure to move might mean that an individual never meets that spouse who would be a great match for them, and never has those children they would have had if they had moved.

3. Estimating the causal impact of migration on spousal or child outcomes may be ill-defined

A common question in the migration and development literature is to attempt to measure the impact of migration and remittances on the labor supply of the spouse, or on child schooling. This typically involves running a regression like:

Y(j) = a + b*Migration(j) + c’X(j) + e(j)

Where Y(j) is the labor supply of the wife of individual j, Migration(j) is an indicator for whether person j has migrated, and X(j) are some controls. The challenge in the literature has then been to find an instrument for migration (e.g. whether person j was selected in a migration lottery). However, if migration changes whether and who person j marries, then even a lottery instrument won’t be enough here – since the spouses we observe of migrants are different people from who they would be had these individuals not migrated.

We discuss several potential solutions to this issue in the paper, which involve being very careful in defining the question of interest and in determining what can be identified. One possibility would be to take only the subset of individuals who were married at some point in time before migration decisions, and then only measure impacts on spousal labor supply for this subset, even if these individuals divorce and so the subset are no longer spouses at the time of the study. A second alternative would be to define the outcome as “total spousal labor supply”, and code this as 0 for migrants who are not married, and then realize the impact will combine the joint effects of selection into and out of marriage, as well as effects on labor supply conditional on marriage. Similar issues apply when looking at child outcomes.

When do we need to worry about this (it’s not just migration)

While our focus is on migration, any big policy change or intervention that can change whether and who people marry will involve similar issues. But they are likely to be strongest for migration, since moving to a new location will change by more the pool of potential partners one is exposed to. These issues are less likely to be as much of a concern for short-term, temporary contractual migration. The issue of considering counterfactual families will apply most severely when migration is anticipated or planned in advance, occurs for younger people still in the process of forming families, and is for longer-term duration migration movements. This certainly describes a lot of international migration.

Policy implications

In addition to complicating efforts to measure causal impacts of migration, considering counterfactual families may also have implications for migration policy. First, many of the details of migration policies will have impacts on decisions of families to form, and to stay together or dissolve, and there can be unintended consequences of policies which take the family structure as fixed and unchanging. Second, if inability to picture counterfactual families is leading individuals to make suboptimal migration decisions, one might wish to explore policy interventions that help individuals better consider these possibilities, such as visualization treatments. Finally, the paper notes implications for how we think about remittances: maximizing remittances should not be a policy goal. A migrant may be better off having their whole family move with them and making no remittances, or forming a different family after migration.

Join the Conversation