Wojciech Hardy, guest blogger, is an Economist at the Institute for Structural Research (IBS) and a PhD student at the Faculty of Economic Sciences of the Warsaw University.

Populations are ageing, globally. Prolonging the working life is one of the most pressing challenges for policymakers around the world. As jobless older people face more difficulties in finding work than prime-aged workers, it is important to support workplace retention before retirement.

The problem, however, is complex: older workers are typically less prepared for technological and educational changes in the labor market. Also the experience of one country is not necessarily the same as another. In our recent working paper we took a look at four neighboring Central and Eastern European countries (CEE4: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia) and found out that job retention among older people varies substantially even across neighboring countries or subpopulations.

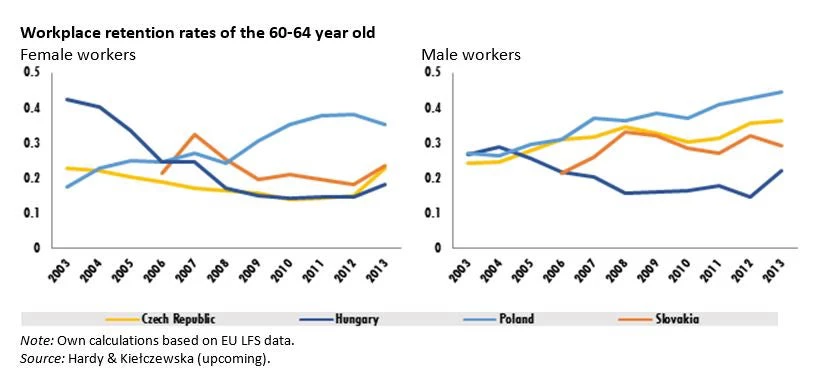

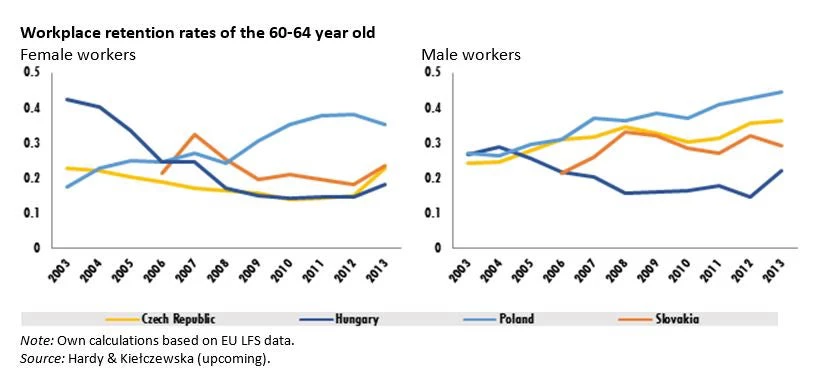

Retention rates – defined as the ratio of workers who remained in the same workplace for at least five years – have changed over the past ten years in the CEE4. Notably, retention rates increased considerably in Poland, but dropped to a comparable extent in Hungary. Moreover, the retention rates also varied between genders, both in terms of changes and general levels.

For male workers, all four countries started at comparable levels in 2003 of 20%-30% but followed different paths afterwards. The retention rate of Czech and Slovakian male workers grew, although less than that of Polish male workers whose retention rate increased a further 18%. For female workers, the initial retention rates in Hungary were the largest in CEE4 (40%) but by 2013 became the smallest (18%). There was also a smaller decrease in Czech Republic before 2013 and close to no change in Slovakia. Poland remains the only country that witnessed significant growth for both women and men, making it the country with highest retention rates among CEE4 in 2013. The opposite (i.e. a significant drop) can be seen in Hungary.

Retention rates generally are higher for male workers. In the case of the Czech Republic the difference between male and female retention rates increased between 2003 and 2013. This suggests that female workers are less likely to remain in their workplace when aged 60-64.

However, the retention rates only show what happened to those who were employed five years earlier, meaning that it fails to address the workers who had already left the labor market or who are preparing to do so via so-called bridge jobs. If we change the index to show the share of retained workers among the whole population five years earlier, the gender gap becomes much more pronounced. The mean difference is now 11%, suggesting that women start becoming underrepresented in the labor market by the age of 55-59.

It is likely that labor market inequalities and institutional factors like gender roles contribute to these differences. For instance, some studies show that female workers are more likely than male workers to drop out of the labor force to take care of their grandchildren.

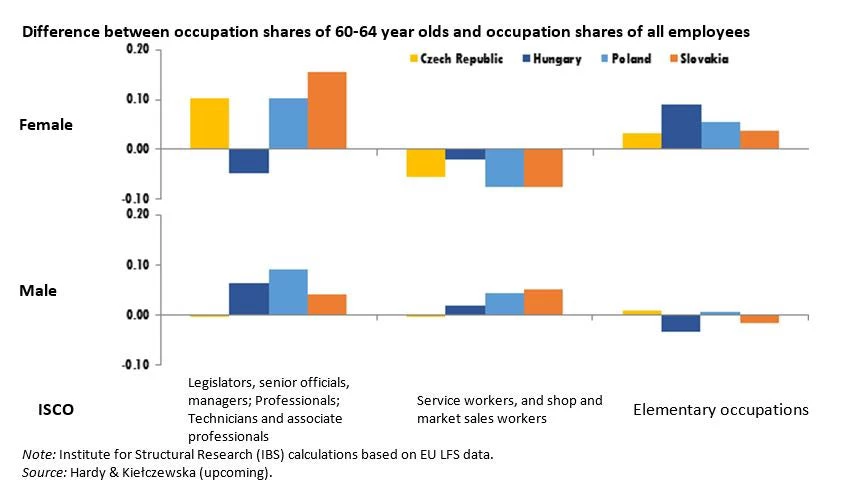

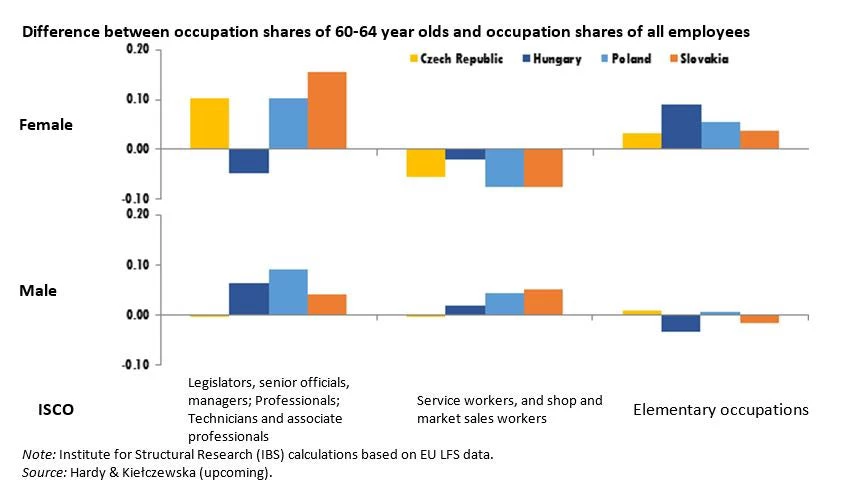

There is also evidence that female workers remain in jobs that are different than those of men. When approaching the retirement age, male workers tend to remain mainly in high-skilled occupations as well as service workers, shop and market sales workers (although this does not apply to the Czech Republic). Older female workers also remained in high-skilled jobs (except in Hungary), but they were unlikely to continue working as service workers, shop or market sales workers. They were very likely to continue working in elementary occupations.

Our findings show that the largest room for improvement in retention rates pertains to women. Their participation drops much earlier than that of men. Moreover, women remain in elementary occupations more often than men but do not do so in service work, nor in shop and market sales work.

This might be related to self-selection or different opportunities. Both of these potential reasons should be studied further to assess a proper policy response. Some lessons can be learned from cross-country studies, for instance in the way that Czech Republic showed little to no job sorting among older men and had the highest share of retained male workers among the whole population. Hungary was the one country where women did not remain in high-skilled occupations and where the sorting of women into elementary occupations was the strongest. While the occupation sorting in Poland was strong, Poland had the largest rise of retention rates among workers for both men and women and the highest share of retained female workers among the whole population through most of the studied period.

Populations are ageing, globally. Prolonging the working life is one of the most pressing challenges for policymakers around the world. As jobless older people face more difficulties in finding work than prime-aged workers, it is important to support workplace retention before retirement.

The problem, however, is complex: older workers are typically less prepared for technological and educational changes in the labor market. Also the experience of one country is not necessarily the same as another. In our recent working paper we took a look at four neighboring Central and Eastern European countries (CEE4: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia) and found out that job retention among older people varies substantially even across neighboring countries or subpopulations.

Retention rates – defined as the ratio of workers who remained in the same workplace for at least five years – have changed over the past ten years in the CEE4. Notably, retention rates increased considerably in Poland, but dropped to a comparable extent in Hungary. Moreover, the retention rates also varied between genders, both in terms of changes and general levels.

For male workers, all four countries started at comparable levels in 2003 of 20%-30% but followed different paths afterwards. The retention rate of Czech and Slovakian male workers grew, although less than that of Polish male workers whose retention rate increased a further 18%. For female workers, the initial retention rates in Hungary were the largest in CEE4 (40%) but by 2013 became the smallest (18%). There was also a smaller decrease in Czech Republic before 2013 and close to no change in Slovakia. Poland remains the only country that witnessed significant growth for both women and men, making it the country with highest retention rates among CEE4 in 2013. The opposite (i.e. a significant drop) can be seen in Hungary.

Retention rates generally are higher for male workers. In the case of the Czech Republic the difference between male and female retention rates increased between 2003 and 2013. This suggests that female workers are less likely to remain in their workplace when aged 60-64.

However, the retention rates only show what happened to those who were employed five years earlier, meaning that it fails to address the workers who had already left the labor market or who are preparing to do so via so-called bridge jobs. If we change the index to show the share of retained workers among the whole population five years earlier, the gender gap becomes much more pronounced. The mean difference is now 11%, suggesting that women start becoming underrepresented in the labor market by the age of 55-59.

It is likely that labor market inequalities and institutional factors like gender roles contribute to these differences. For instance, some studies show that female workers are more likely than male workers to drop out of the labor force to take care of their grandchildren.

There is also evidence that female workers remain in jobs that are different than those of men. When approaching the retirement age, male workers tend to remain mainly in high-skilled occupations as well as service workers, shop and market sales workers (although this does not apply to the Czech Republic). Older female workers also remained in high-skilled jobs (except in Hungary), but they were unlikely to continue working as service workers, shop or market sales workers. They were very likely to continue working in elementary occupations.

Our findings show that the largest room for improvement in retention rates pertains to women. Their participation drops much earlier than that of men. Moreover, women remain in elementary occupations more often than men but do not do so in service work, nor in shop and market sales work.

This might be related to self-selection or different opportunities. Both of these potential reasons should be studied further to assess a proper policy response. Some lessons can be learned from cross-country studies, for instance in the way that Czech Republic showed little to no job sorting among older men and had the highest share of retained male workers among the whole population. Hungary was the one country where women did not remain in high-skilled occupations and where the sorting of women into elementary occupations was the strongest. While the occupation sorting in Poland was strong, Poland had the largest rise of retention rates among workers for both men and women and the highest share of retained female workers among the whole population through most of the studied period.

Join the Conversation