The number of children a woman has influences her decision to work. Understanding the reasons behind fertility choices sheds light on one of the determinants of female labour market participation. This is particularly relevant in low income countries, which, on average, are characterised by high fertility and low female employment.

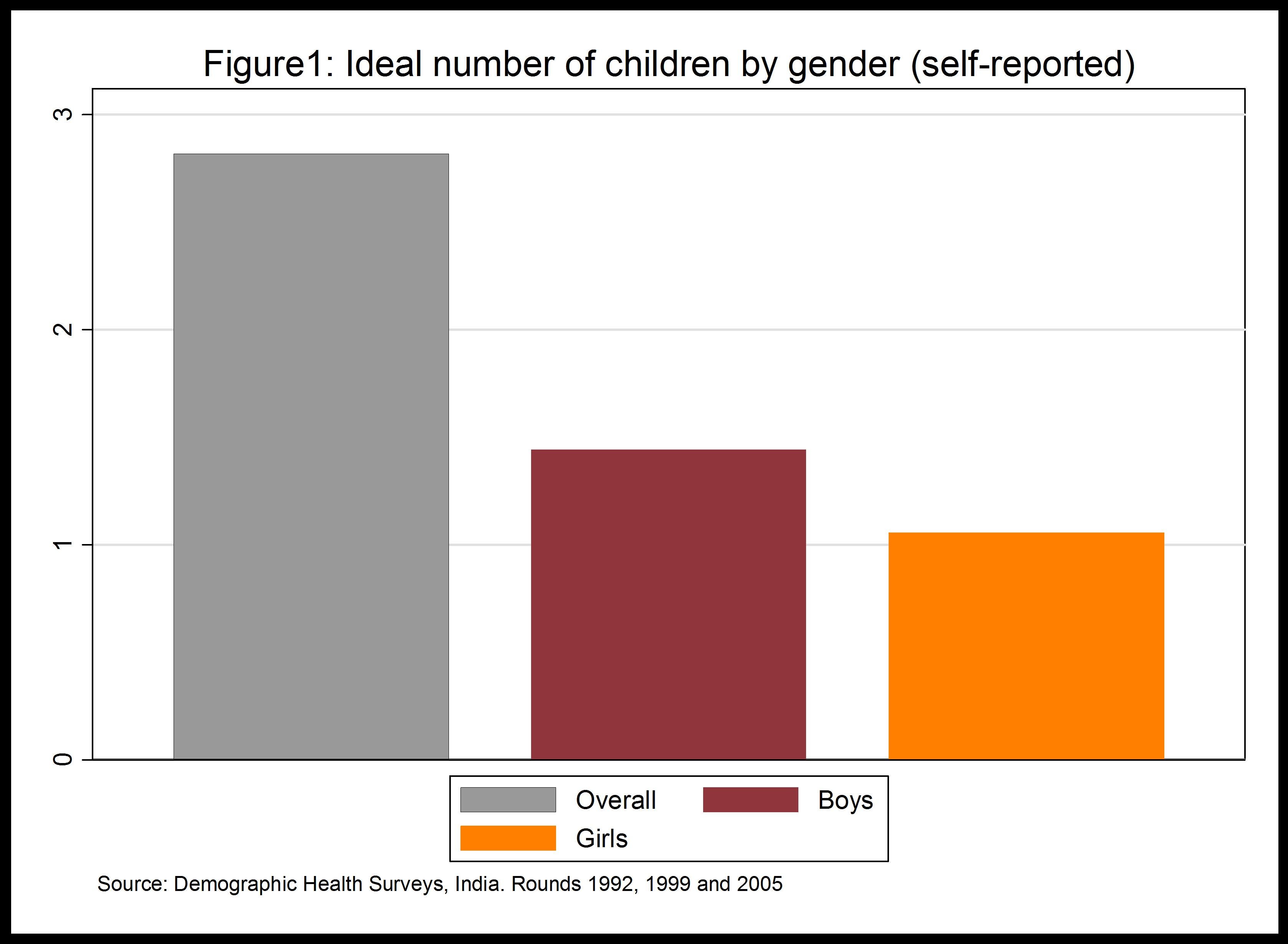

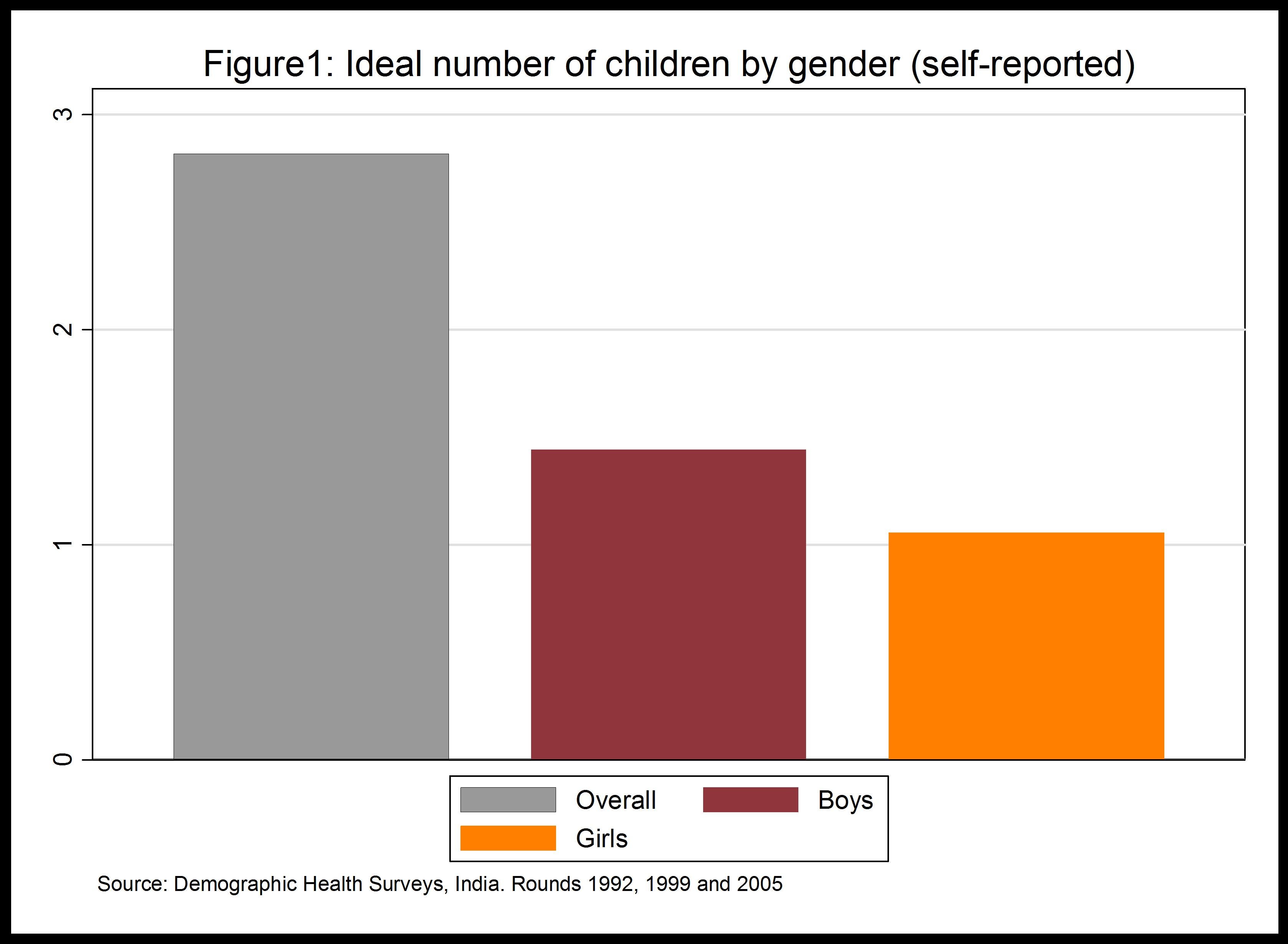

In Southeast Asia, parental gender preferences have been found to influence fertility levels. If parents, for instance, want a certain number of boys, they will only stop having children once they reach their ideal number of sons. In India such preferences for sons is particularly pronounced. When asked about their ideal number of children (figure 1), many Indian mothers state that they would like 2.8 children of which 1.4 should be boys, 1.0 girls and 0.4 of either gender.

These attitudes are also reflected in reproductive choices: 54% of families in the sample stop childbearing after having had a boy and only 46% after a girl. Whilst we know that such reproductive behaviour increases fertility, the mechanisms giving rise to these fertility stopping rules remain less explored. The most common explanation is that, due to cultural reasons, boys are perceived to be more valuable than girls. This post argues that fertility choices observed in India can be explained by the fact that daughters are more expensive to raise than sons.

The focus here is on an old Indian custom, which raises the cost of daughters: at many marriages, the brides’ parents pay a dowry to the groom or his family. These transfers are very common in India, a survey carried out in the 1970s and 1980s suggests that 4 out of 5 households either paid or received dowries. Furthermore, the amounts transferred are very large: research estimates that dowries can be up to two thirds of the bride’s family’s assets.

From the perspective of the parents, dowries drive a wedge between the costs of raising a son and a daughter. For each girl born, parents will expect to make a large payment in the future. The birth of a boy, by contrast, will be associated with a large receipt of payments. Given these income streams, it is hardly surprising that parents value boys more than girls and that many adjust their fertility behaviour so as to end up with more sons than daughters.

The dowries that parents expect to pay for their children depend on the legal framework of the time. In 1985, the Indian government tightened the laws regarding dowries by increasing the monitoring of these transfers as well as the punishments for offenders. This policy change provides an interesting natural experiment, which helps us to understand how parents adjust their behaviour in response to a sudden change in the dowries they expect to pay.

By tightening the dowry laws, the new policy decreased the dowry parents expect to pay at their daughters’ wedding thus essentially lowering the costs of female births. This had a significant impact on fertility choices. As mentioned above, before the policy, the probability of having a child depends on whether the parents have more boys than girls or vice versa. After the law, by contrast, parents become more indifferent to the gender of their children (the probability of another birth does not vary significantly by whether parents have more sons or more daughters).

By becoming more indifferent to the gender of their children, parents focus on the total number of children instead of sons. This decreases their fertility rates. In fact, the anti-dowry laws of 1985 are estimated to have lowered lifetime fertility by almost 0.1 children. Even such relatively small changes in family size have the potential of making a marked impact on the economy as a whole for two reasons. First, the size of the Indian female population in working age is very large, around 250 million according to the 1991 census. Second, around that time, female labour force participation in the continent was very low, around 35% most of which were working in agriculture. Thus, by changing the costs of children, anti-dowry laws may have significant unintended consequences for female employment.

Marco Alfano is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Economics, University College London. The working paper version of this blog is available here:

In Southeast Asia, parental gender preferences have been found to influence fertility levels. If parents, for instance, want a certain number of boys, they will only stop having children once they reach their ideal number of sons. In India such preferences for sons is particularly pronounced. When asked about their ideal number of children (figure 1), many Indian mothers state that they would like 2.8 children of which 1.4 should be boys, 1.0 girls and 0.4 of either gender.

These attitudes are also reflected in reproductive choices: 54% of families in the sample stop childbearing after having had a boy and only 46% after a girl. Whilst we know that such reproductive behaviour increases fertility, the mechanisms giving rise to these fertility stopping rules remain less explored. The most common explanation is that, due to cultural reasons, boys are perceived to be more valuable than girls. This post argues that fertility choices observed in India can be explained by the fact that daughters are more expensive to raise than sons.

The focus here is on an old Indian custom, which raises the cost of daughters: at many marriages, the brides’ parents pay a dowry to the groom or his family. These transfers are very common in India, a survey carried out in the 1970s and 1980s suggests that 4 out of 5 households either paid or received dowries. Furthermore, the amounts transferred are very large: research estimates that dowries can be up to two thirds of the bride’s family’s assets.

From the perspective of the parents, dowries drive a wedge between the costs of raising a son and a daughter. For each girl born, parents will expect to make a large payment in the future. The birth of a boy, by contrast, will be associated with a large receipt of payments. Given these income streams, it is hardly surprising that parents value boys more than girls and that many adjust their fertility behaviour so as to end up with more sons than daughters.

The dowries that parents expect to pay for their children depend on the legal framework of the time. In 1985, the Indian government tightened the laws regarding dowries by increasing the monitoring of these transfers as well as the punishments for offenders. This policy change provides an interesting natural experiment, which helps us to understand how parents adjust their behaviour in response to a sudden change in the dowries they expect to pay.

By tightening the dowry laws, the new policy decreased the dowry parents expect to pay at their daughters’ wedding thus essentially lowering the costs of female births. This had a significant impact on fertility choices. As mentioned above, before the policy, the probability of having a child depends on whether the parents have more boys than girls or vice versa. After the law, by contrast, parents become more indifferent to the gender of their children (the probability of another birth does not vary significantly by whether parents have more sons or more daughters).

By becoming more indifferent to the gender of their children, parents focus on the total number of children instead of sons. This decreases their fertility rates. In fact, the anti-dowry laws of 1985 are estimated to have lowered lifetime fertility by almost 0.1 children. Even such relatively small changes in family size have the potential of making a marked impact on the economy as a whole for two reasons. First, the size of the Indian female population in working age is very large, around 250 million according to the 1991 census. Second, around that time, female labour force participation in the continent was very low, around 35% most of which were working in agriculture. Thus, by changing the costs of children, anti-dowry laws may have significant unintended consequences for female employment.

Marco Alfano is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Economics, University College London. The working paper version of this blog is available here:

Join the Conversation