A primary school in Poland. Credit: Anna Cieślarczyk

A primary school in Poland. Credit: Anna Cieślarczyk

(This blog is based on a keynote presentation delivered by the author at the Jobs and Development Conference 2020)

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that 79.5 million people are currently displaced from their home regions as a result of interstate wars, civil conflict, or natural disasters. The trauma of forced displacement resonates through several generations and leaves diverse and unexpected footprints across the lives of the refugees and their families. Economists have long hypothesized that being forcibly uprooted increases the subjective value of investing in portable assets, particularly education. However, this “uprootedness hypothesis” has been difficult to test.

Displaced families typically differ from locals along many socioeconomic and cultural characteristics, such as ethnicity, language, and religion. Labor market competition with locals can also affect the educational choices of these families, who – unlike locals – often have no access to land or other productive physical assets.

But we found a unique situation at the end of World War II that allows us to study the uprootedness hypothesis without these constraints. Drawing on our research from this time, our recent American Economic Review paper is the first to provide empirical support for the uprootedness hypothesis. Here’s what we learned and some possible policy implications.

Historical background

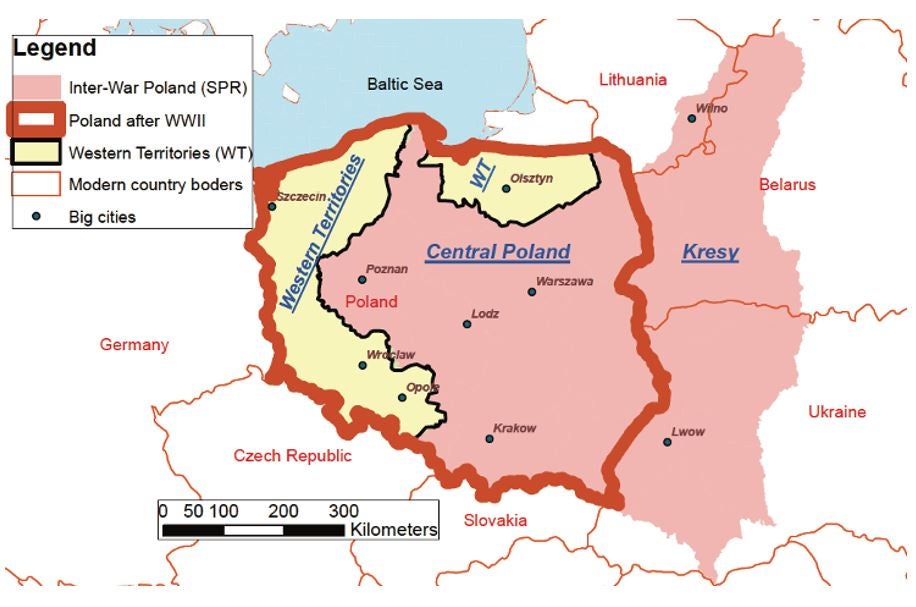

At the end of WWII, the Polish borders were redrawn, resulting in large-scale forced displacement. We focused on the case of over two million Polish migrants who were forced to move away from Kresy, a region in the eastern borderlands of Poland that was taken over by the USSR following the end of the war. Polish expellees from Kresy were primarily resettled to the newly acquired ‘Western Territories’, which were taken over from Germany (and from which Germans were forcibly expelled). Some families from Kresy also settled in the territories of Central Poland, which were Polish in the inter-war period and remained Polish after WWII (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Poland’s territorial change after WWII

Our study

We studied the long-term effects of forced displacement, analyzing the generations of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of the expellees from Kresy. We combined data from historical censuses with newly collected survey data to test our hypotheses.

We found that Polish people with a family history of forced displacement are significantly more educated today than other Poles who were not forced to move but who had the same ethnic, linguistic, and religious background. The descendants of Kresy migrants are 11.2 percentage points more likely to finish secondary education and 8.8 percentage points more likely to graduate from university compared to all other Polish subgroups. These differences amount to about one extra year of schooling for descendants of Kresy migrants, which in turn translates into better labor market outcomes and substantially higher incomes.

Importantly, before WWII, Polish inhabitants of Kresy were, if anything, less educated than compatriots living elsewhere.

We explored the mechanism behind this result and showed that forced displacement caused a shift in preferences toward investment in human as opposed to physical capital . In particular, the descendants of displaced families value material goods less and have a stronger aspiration for education of their children , compared to other Polish subgroups. They also own fewer physical assets relative to what they can afford, given their higher incomes. We rejected a variety of alternative potential explanations.

Policy implications

The mechanism behind the educational advantage of the displaced population has important policy implications in the face of the large refugee flows seen in many parts of the world today.

The shift of preferences among refugee communities toward valuing investment in human capital over investment in physical capital should be used to guide aid priorities. A policy recommendation emerging from our study is the proposal that governments in countries receiving displaced individuals should foster their access to education.

While the international aid community does consider education as an important factor in reducing economic and social marginalization of refugees, our results suggest that the benefits of providing schooling for displaced individuals and their children may be even greater than previously thought .

Join the Conversation