We recently hosted our first Jobs and Development Conference, and one of the key topics we discussed was the role of governments in creating jobs. We had about 260 participants, and 68 papers were presented (more than 150 considered but not selected for presentation, a high rejection rate that attests to the quality of the papers that were presented).

One of the plenary sessions that I chaired focused on the role of governments in designing and implementing jobs strategies. The consensus has been that jobs will come if countries just fix markets and institutions to promote investment and economic growth. But this is a very simplistic view.

The fact is, we know surprisingly little about the link between investment policies and jobs. We might all believe - at the aggregate level - that more investment brings more output and more jobs. But the number and the distribution of those jobs across population groups matters a lot.

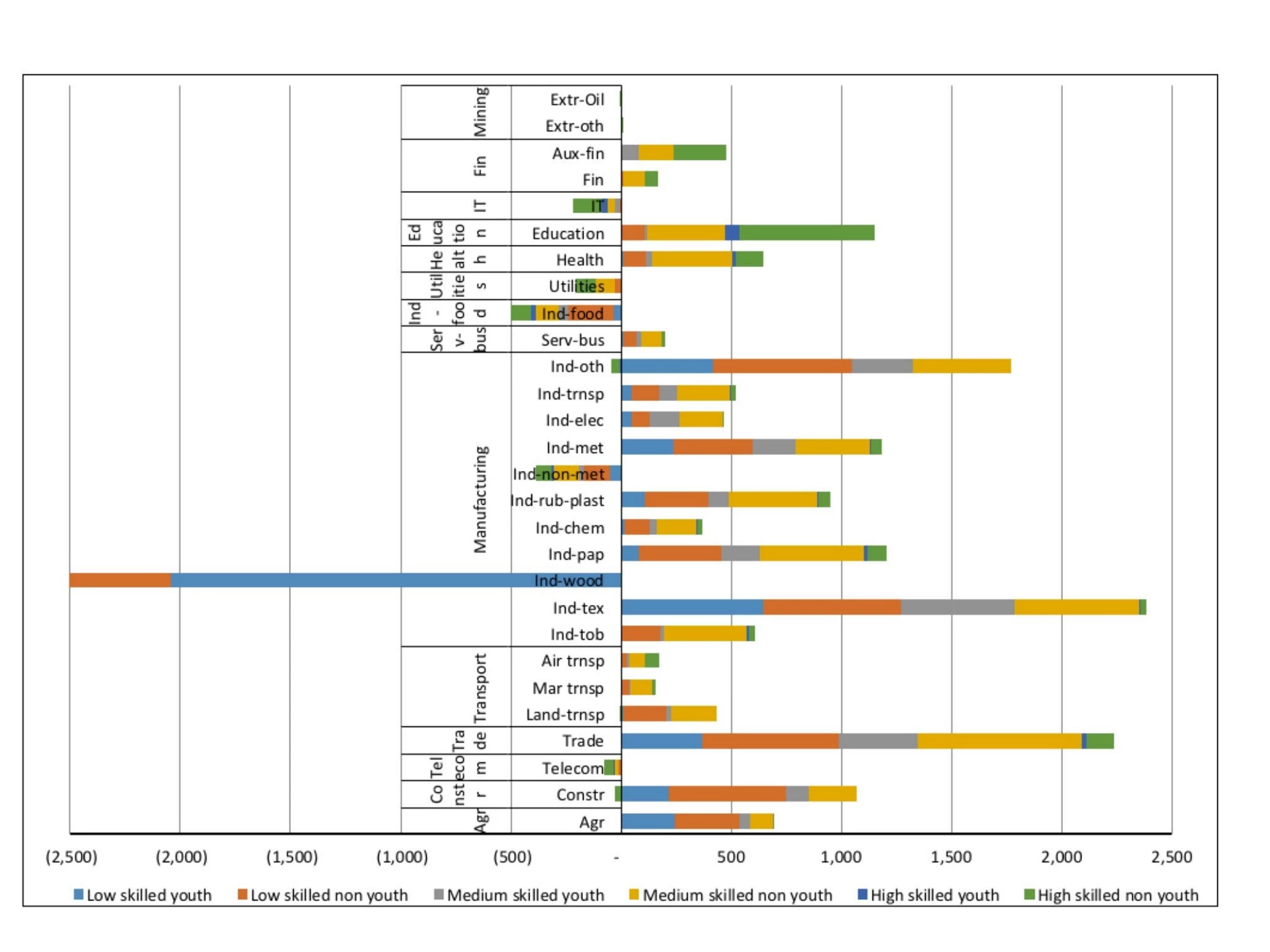

Different types of investment create and destroy jobs with different profiles in terms of skills, gender, age, and geographic region. For example, the chart below shows the change in the number of jobs by skill level and age of a $10 million investment in each sector of the Tunisian economy. This shows that the number and types of jobs created/destroyed vary widely across sectors.

The truth is that policies that simply increase investments and allocated them to the sectors with the highest rates of return, might not create the number and distribution of jobs needed to achieve social objectives such as reducing poverty and inequality, or improving employment prospects for women and youth. Essentially, if jobs have social externalities, governments might need to subsidize the creation of certain jobs and tax the destruction of others.

I had the pleasure to share the stage with Felipe Larrain Bascunan, Chile’s former Minister of Finance, Njuguna Ndung’u Kenya’s former Central Bank Governor and Montek Singh Ahluwalia, the former Deputy Chairman of India’s Planning Commission. We discussed the challenges countries face, looking at the evidence from Latin America, Africa, and India. We concluded that although the details are country specific there are common challenges: creating more jobs in the formal sector of the economy; improving the quality of the many informal jobs that are out there and that will not disappear; and removing barriers faced by vulnerable population groups as they move from unemployment/inactivity into a job or from low to higher quality jobs. We also discussed the challenges created by technological change: new technologies will bring new opportunities for job creation but will also destroy jobs. We need to understand both processes.

Where there was a lot more room for discussion was on specific policies. Much was said about the “consensus” types of policies, such as macroeconomic stability, business environment, infrastructure and access to finance. But there was little about targeted regional and sectoral policies, which I think will be the game changer for jobs.

Montek spoke about the importance of urbanization policies – a common topic during the conference. We know that good jobs are created where people and business come together. But all people cannot move to urban centers, so there might be a role for governments to support the emergence of secondary towns that attract investments and economic activity.

On sectoral policies Felipe was categorical: let us not pick winners. We have tried in the past and it doesn't work. But he agreed at the end that governments do have a role to play in addressing coordination and learning failures that act locally. These can preclude the emergence of certain economic activities within specific sub-sectors and value chains.

You just have to visit rural areas in middle and low income countries to see how these failures operate. Two weeks ago, I was visiting Kafue, south of Lusaka, in Zambia. We met a community of farmers who for years have been living on government handouts because they could not properly cultivate their 500 hectares of land and commercialize their production. The land was below sea level, it would flood during the rainy season and then be too dry for the rest of the year. The farmers didn’t know about new seeds and new production technologies. And they didn’t know how to set up, finance, and implement a business plan to change the status-quo. The opportunities were there but they didn’t materialize: free markets were not enough to unleash the potential. Finally, donors and investors were mobilized to work with the community on an agricultural development project. It has taken eight years but they will soon be producing wheat and sugar cane in volume. As they told us, the children of the community will be able to have a very different life.

This showed me that governments need to be able to understand the microeconomics of different sub-sectors and act to enable investments and job creation where appropriate. This is not about picking and protecting winners.

So for me, the main message from the plenary session was that we need to move beyond growth strategies. We now need to focus on jobs strategies and poverty reduction strategies. If jobs are the center of the development process as discussed in the 2013 World Development Report, then the types of policies that governments implement need to move beyond the Washington Consensus – focusing more on targeted regional and sectoral policies that can be game changers for job creation.This post is part of a series of blogs covering key themes from the Jobs and Development Conference, hosted by the World Bank Jobs Group and the Network on Jobs and Development. Related blog in this series can be found here.

Follow the World Bank Jobs Group on Twitter @wbg_jobs.

Join the Conversation