It is well known that successful counter-insurgency operations need to have a development component. However, the challenge is getting the right mix of policy measures. An examination of experiences from India may help us identify appropriate and effective counter-insurgency strategies.

It is well known that successful counter-insurgency operations need to have a development component. However, the challenge is getting the right mix of policy measures. An examination of experiences from India may help us identify appropriate and effective counter-insurgency strategies.

Many states in India are experiencing Naxalite insurgency. Drawing inspiration from Communist ideology, particularly Maoist ideology, the Naxalites believe that an armed insurrection to overthrow the state is an important step to achieve a classless society.

In 2013, the Government of India declared that there are 106 districts which are experiencing Naxal related violence. Today, the most impacted states are Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Bihar and West Bengal. Since 1980, more than 15,000 people lost their lives due to Naxalite related violence. Close to half of these deaths (6,700 deaths) happened during 2005-2015 and this year 130 people were killed in Naxalite related incidents.

While various states in India have been struggling to contain Naxalism, there was a sharp decline in the fatalities caused by this left-wing Extremism in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. In 2005, the total fatalities were 320 and this came down to just four in 2015. What explains the decline of Naxalism in the Telangana and Andhra Pradesh regions in India and what are the lessons to be learnt? Specifically what was the interface between job creation and decline of Naxalism?

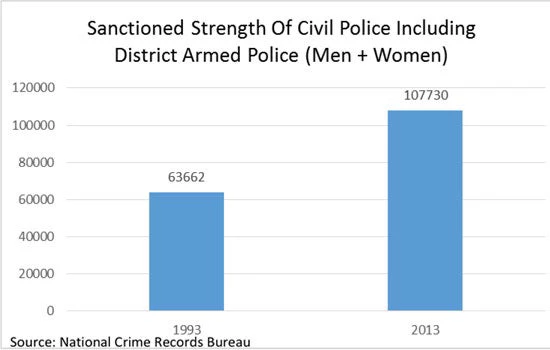

The state government adopted a three-pronged strategy in response to Naxal related violence. First, the government of Andhra Pradesh did not depend on the police forces from the Union government. Instead, it created various specialized units such as the Greyhounds to carry out counter-insurgency operations. By increasing recruitment, the police force was also strengthened in terms of numbers as well. For instance, the total strength of the Andhra Pradesh police force went from 63,662 in 1993 to 107,730 in 2013.

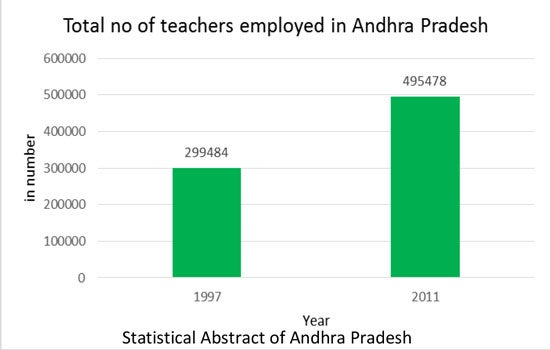

Second, the state government sought to create employment opportunities at the grass roots. For instance, there were 299,484 school teachers in 1997, which increased to 495,478 in 2011. Further, various schemes of the central government such as the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act also added impetus to the state government’s effort to create employment at the grass roots. In 2013-2014, under this scheme 6,565,827 households were allocated work in Andhra Pradesh and of this, nine districts in Telangana regions accounted for approximately 2,880,773 households. Further, all the districts of Telangana (except Hyderabad) received additional funding under Backward Grant Regions Grant Fund (BRGF) of Rs10 crores ($1.5 million) per district. A substantial portion of these funds were earmarked for local infrastructure projects such as rural water supply, construction of social welfare hostels and rural electrification.

The government of Andhra Pradesh also initiated construction of large numbers of irrigation/hydro-electric projects (30 major and 18 medium irrigation projects). Simultaneously, a massive rural housing program called the Integrated Novel Development in Rural Areas and Model Municipal Areas was launched in 2006. This resulted in the construction of almost 617,769 house units in Phase I. While there have been allegations of corruption, the projects generated significant employment opportunities in the short-term.

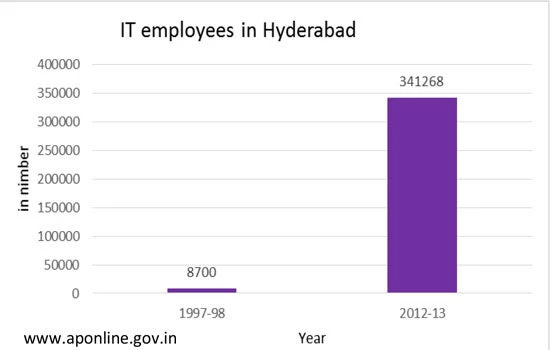

Third, Hyderabad, the capital city of Andhra Pradesh, emerged as a prominent software hub. The number of employees in Information Technology sector in Hyderabad witnessed an exponential increase from about 8,700 people in 1997-1998 to approximately 341,268 in 2012-2013. All these new jobs might not have gone to the people from Andhra Pradesh. However, it should be noted that according to the study conducted by NASSCOM, a job in the IT sector creates about four jobs in other sectors. The emergence of the IT sector and the spillover impact in other sectors generated a strong perception in the state that the private sector employment opportunities are on the rise.

The Andhra Pradesh experience is broadly in consonance with Paul Collier’s argument that construction of infrastructure gives high returns in facilitating a movement from conflict to post-conflict situations. Further, the question is not if private sector can generate sustainable employment opportunities in conflict situations but where should the private sector be deployed in conflict situations. In areas that are under government control, the private sector should be promoted. The growth of private sector led employment, even in small geographic areas will add momentum to politics of aspiration as opposed to politics of grievance. And in areas that are under the shadow of the insurgency, government-led employment schemes will yield better results.

Join the Conversation