Dr Ali Mehdi, a guest blogger, is Fellow at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) in New Delhi

India’s policymakers are concerned with the employability of their working-age populations. Within six months of assuming office, the new administration established a Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, boosting the skill development initiatives of the previous regime in a major way. Within the next six months, it also brought out a highly promising ‘National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship 2015’. However, like its precursor, the ‘National Policy on Skill Development 2009’, it takes 2022 as the timeframe for its skilling initiatives. Its focus is on those who are in the workforce at the moment and those who will enter it up to that year.

This focus and the initiatives for skill development seek to reap India’s demographic dividend largely in the context of low- and semi-skilled manufacturing jobs. This is significant. But Indian policymakers should concurrently focus on preparing a highly skilled and dynamic workforce if they are to realize their vision of developing India into a knowledge economy.

Fulfilling the requirements of today’s industry – which has been the predominant focus of both skills policies – does not mean that we cannot work towards a vision of the future economy and the workforce required for it. In this context, it is important to realize that India’s workforce will surpass that of China’s in 2030, and peak in 2050, so we have the widest window of opportunity to realize our workforce ambitions for a knowledge economy with respect to those who are in their infancy today and in the next two decades. The gradual declines in our child dependency ratio can potentially help us enjoy benefits of a wider demographic window, provided the human capital dimensions of this population segment are addressed.

The World Economic Forum’s Human Capital Report 2013 argues that while, ‘long-term thinking around human capital often does not fit political cycles or business investment horizons … lack of such long term planning can perpetuate continued wasted potential in a country’s population and losses for a nation’s growth and productivity’. Using measures to indicate the quality of early childhood, the report ranked India 78th on overall human capital status out of 122 countries – 63rd in education and 112th in health and wellness.

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) might enhance the employability prospects of the present and near-term labor force. However, if we wish to become a knowledge economy, with highly skilled and dynamic rather than abundant, cheap labor force, we should revamp our profoundly inadequate, inefficient and inequitable early health and education systems.

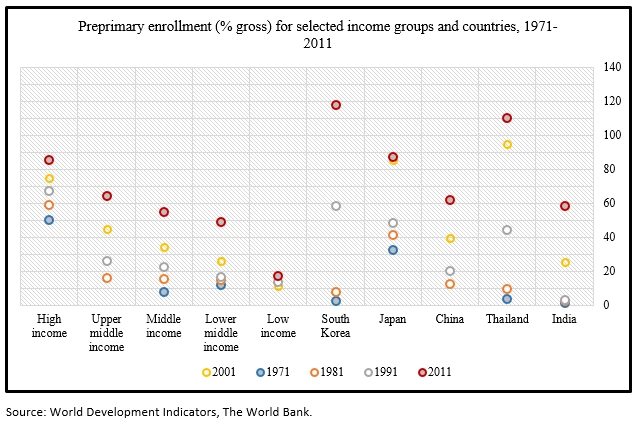

In our recent paper, Human capital potential of India’s future workforce’(ICRIER Working Paper No. 308), we have highlighted the significance of early health and preschooling for employability in a knowledge economy, which has thus far remained neglected in the human capital discourse. The role of primary education in the success of East Asian economies in particular, and that of advanced economies in general, has been widely recognized. But we tend to overlook the rise in preprimary enrollment in these against other countries over the decades. The chart below shows how preprimary enrollment is clearly graded by income status. As far as individual countries are concerned, although India, Thailand and South Korea started out at similar levels in 1971, preprimary enrollment rose dramatically from early 1980s in the latter two, with India now being two decades behind South Korea, despite major improvements during the last two decades.

Preprimary schools (with families) share the onus of inculcating a set of employability skills, referred to as non-cognitive, soft, generic or life skills. While these skills are difficult to measure, they play a significant role in determining formal schooling and later labour market success. This is not just supported by psycho-educational research that stresses the importance of early childhood interventions. They foster emotional security and motivation in children – traits that trigger child exploration in early years of life (see the work of Prof James Heckman in particular).

This is also supported by emerging empirical evidence based on employer surveys. Soft skills enhance employability directly as well as through their indirect impact on professional trainability. The Chinese education system has been criticized for promoting memorization and conformity at the cost of creativity and analytical rigor, as a result of which, as multinational employers in China complain, while it is easy to find employees for junior positions, it is difficult to get good managers.

Given the rising recognition of the importance of soft skills, PISA has decided to include non-cognitive skills as part of its triennial survey that aims to evaluate education systems worldwide by testing the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students. The World Bank’s STEP framework offers relevant guidelines to policymakers, particularly in developing countries, to develop employable skills and enhance the productivity of their labour force, starting with ‘getting children off to the right start’. Indian policymakers need to pay heed to this neglected aspect of policy.

Join the Conversation