Tanger-Med, a cargo and passenger port located about 40 km east of Tangier

Tanger-Med, a cargo and passenger port located about 40 km east of Tangier

Think of an of an image of globalization and you may picture a Bangladeshi woman in a sari stitching together a t-shirt displaying a pop-culture phrase for a fast-fashion outlet in London or Los Angeles. Such is the cultural prominence of manufacturing global value chains (GVCs), particularly in the apparel sector. But how can we ensure that these GVCs, which deliver massive benefits to consumers in the West, also improve the livelihoods of that Bangladeshi garment worker and the millions of others employed in global supply chains? This issue is taken up in the World Bank’s recent World Development Report 2020: Trading for Developing in the Age of Global Value Chains.

In Bangladesh, integration into the apparel GVC led to the creation of more than 3 million waged jobs beginning in the early 2000s. With around 70 percent of those new jobs captured by women, this contributed to female labor force participation rising by 10 percentage points in the first decade of the 2000s.

Garment sector employment is widely recognized as catalyst for Bangladesh’s sustained growth and large-scale poverty reduction. It has also had significant positive social impacts. For example, a 2015 study showed that households in villages near garment factories increased their investment in the education of female children and raised the average marrying age for young women.

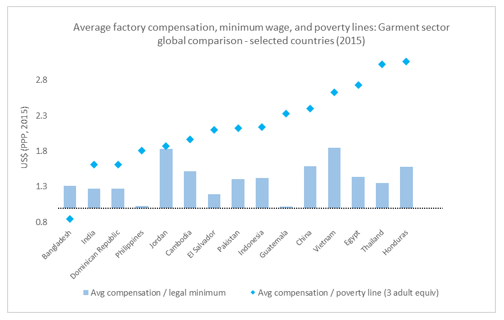

That’s the good news. On the other hand, most workers in the sector still take home salaries of less than $100 per month. And while average monthly wages rose by over 40 percent between 2010 and 2016, that hardly kept up with rapidly rising costs in Dhaka. In fact, earnings from working in the garment GVC in Bangladesh are hardly sufficient to keep a family out of poverty (see figure below). Of equal concern is the fact that many workers toil in highly unsafe working conditions.

To be fair, these negative outcomes are not inherently the fault of GVCs. While pricing pressure from global lead firms contributes to downward pressure on wages, workers in export-oriented factories still earn more than they would in equivalent factories serving the domestic market.

Global lead firms, responding to demands by civil society and consumers in their home markets, are also at the forefront of improving working conditions in offshored factories, typically through the establishment of standards that are audited across supply chains. They also participate in initiatives like the ILO-IFC Better Work Program, which covers nearly 2.5 million workers in 1,700 GVC-linked garment factories in eight countries. Better Work has not only contributed to improved compliance rates in GVC factories, but also demonstrated that complying with labor standards actually contributes to higher productivity and profits.

Firm-based initiatives can have a broader impact,if host countries strengthen monitoring and enforcement capacity of labor inspection regimes and build robust labor market institutions, including support for collective bargaining, freedom of association, and social dialogue.

Home countries of global lead firms can also use policy to promote compliance. For example, in 2017, France enacted the Duty of Vigilance Law, which mandates large French companies to publish and implement a plan to identify and prevent human rights risks throughout their global supply chains.

Government policy also has an important role to play to help mitigate the inherent adjustment costs that result from shifts in global supply chains, which tend to be concentrated in certain locations and have long-lasting effects on lower-skilled workers. Although government policies should avoid restrictions on trade, investors, and employers, governments can support workers through policy interventions that combine social protection with skills training and mobility support.

For example, Denmark’s “flexicurity” model gives businesses the freedom to hire and fire workers with relatively few restrictions, while also providing a generous, broad-based unemployment benefit system that cushions the negative income effects on displaced workers. A key feature of Denmark’s system is the significant investment in active labor market programs to enhance employability and connect workers to jobs.

The World Bank Group, development partners, and policymakers around the world are broadly united in seeking to promote countries, sectors, and firms to integrate into GVCs. From copper miners in Chile to smallholder cashew farmers in Cote d’Ivoire and to female factory workers in Bangladesh, interventions seek to use the power of a GVC approach to facilitate growth and boost livelihoods. At the same time, we must recognize that in the context of rapid technological change and evolving patterns of globalization, the impacts of GVCs on workers are nuanced and, as always, there will be winners and losers. Leveraging our policy and program instruments to support both GVCs and the workers within them is the key to ensuring the development impacts of GVCs are inclusive and sustainable.

Join the Conversation