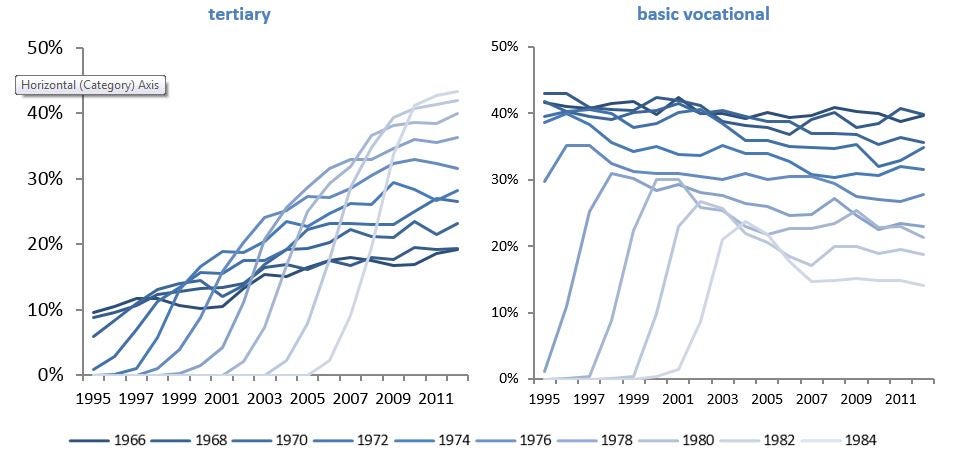

One of the most important phenomena to have emerged during the 25 years of Polish transition is the educational boom. One crucial aspect has been the expansion of tertiary education. At the end of the 1990s, 25% of 20 year olds in Poland studied at the tertiary level. Now that figure has doubled. Figure 1 shows that the share of those obtaining university degrees has been higher for every next cohort entering the Polish labour market. At the same time, the popularity of basic vocational education has decreased strongly.

Nevertheless, the number of university students has grown rapidly from 400,000 in 1990 to 1.6 million in 2000 to a peak of 1.9 million in 2005. As a result, the proportion of people aged 25-64 years with tertiary degree has increased from 12% in 2001 to 26% in 2013, the highest increase in the EU. Among those aged 25-34 years it has increased from 15% to 42% (compared to 24% to 36% in the EU27). A strong improvement in educational indicators has also been experienced by other New Member States (particularly Lithuania, Latvia, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia), but in Poland the process was most pronounced and it provides useful lessons for other transforming countries.

Figure 1. Educational structure of selected cohorts according to LFS, 1995-2012 (percentage of people with a given level of education). Notes: The legend gives the cohort’s year of birth. Minor fluctuations may result from the selection bias. Source: IBS (2014).

The educational boom bodes well for Poland’s rapidly ageing population. Poland is one of three EU countries whose workforce is expected to shrink the most in coming years. According to the most recent Eurostat demographic forecast (Europop, 2013), by 2040 the number of people at working age in Poland will have fallen by 4.62 million (17%) compared to 2013. By 2020 the Polish labour market will lose 1.66 million people of working age. This is equivalent to the current size of the entire working age population in one of 16 administrative regions (Łódzkie). The share of those aged 50-74 in the age group 15-74 will increase from 37% in 2012 to 43% in 2030. By 2050 is will be half of those aged 15-74 will be over 50.

At the same time, in a recent report “ Employment in Poland - Labour in the Age of Structural Change” we calculated that due to the educational boom, the share of those with primary or lower secondary education will drop from 15%-17% now to 5%-6% in 2030. The number of people with basic vocational education will also decline, mainly among men. The share of those with tertiary degree will increase – among men to 26% in 2030 and 36% in 2050, while among women to 38% and staggering 52%, respectively. Moreover, by 2030 most of beneficiaries of educational boom will prime-aged (cf. Figure 2). There will be less people on the labour market, but they will be better educated and should be much more productive than the current workforce, cushioning the impact of ageing on the economy.

Figure 2. Projection of the educational structure of the population aged 15-80 years, baseline scenario, 2012 and 2030. Source: IBS (2014).

However, the structure of education matters. In this regard the Polish system has been much less forward-looking. Social and business-related studies still dominate. But in comparison to other European countries, Poland has relatively many more students of education, but much fewer students of health and social services (cf. Figure 3). This doesn’t bode well for population ageing, as there will be a surplus of teachers and a shortage of care-takers and gerontologists, although this may well shift in time if there is a change in demand within the labor market.

Between 2007 and 2011 the share of newly enrolled students in social and economic departments dropped from 40% to 33%, whereas admissions to teacher studies dropped by 2.8%. This was accompanied by an increase in the share of enrolments at technical faculties from 13% to 18%, and in medicine. However, the cohorts entering universities in the last five years (born between 1990 and 1994) were 21% smaller than cohorts riding the initial wave of educational boom (born 1980-1984).

Furthermore, the cohorts entering in 2015-2019 (born 1996-2000) will be 38% smaller than the cohort born 1980-1984. This may suggest that the current skill mismatches could persist for the next decade or two. This will pose big challenges for a system not suited to providing life-long learning.

Figure 3. Structure of tertiary education by groups of faculties in 2011 in Poland, Germany and the EU. Source: IBS (2014).

The lessons from the Polish educational boom show that tertiary education can be expanded relatively quickly, especially when the demand for skilled labour grows, wage premiums are high and the private providers are allowed to cater to the growing demand for education. However, what seems tougher is ensuring that the structure of education faculties and the skills being taught reflect not only the current demands and future needs.

Nevertheless, the number of university students has grown rapidly from 400,000 in 1990 to 1.6 million in 2000 to a peak of 1.9 million in 2005. As a result, the proportion of people aged 25-64 years with tertiary degree has increased from 12% in 2001 to 26% in 2013, the highest increase in the EU. Among those aged 25-34 years it has increased from 15% to 42% (compared to 24% to 36% in the EU27). A strong improvement in educational indicators has also been experienced by other New Member States (particularly Lithuania, Latvia, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia), but in Poland the process was most pronounced and it provides useful lessons for other transforming countries.

Figure 1. Educational structure of selected cohorts according to LFS, 1995-2012 (percentage of people with a given level of education). Notes: The legend gives the cohort’s year of birth. Minor fluctuations may result from the selection bias. Source: IBS (2014).

The educational boom bodes well for Poland’s rapidly ageing population. Poland is one of three EU countries whose workforce is expected to shrink the most in coming years. According to the most recent Eurostat demographic forecast (Europop, 2013), by 2040 the number of people at working age in Poland will have fallen by 4.62 million (17%) compared to 2013. By 2020 the Polish labour market will lose 1.66 million people of working age. This is equivalent to the current size of the entire working age population in one of 16 administrative regions (Łódzkie). The share of those aged 50-74 in the age group 15-74 will increase from 37% in 2012 to 43% in 2030. By 2050 is will be half of those aged 15-74 will be over 50.

At the same time, in a recent report “ Employment in Poland - Labour in the Age of Structural Change” we calculated that due to the educational boom, the share of those with primary or lower secondary education will drop from 15%-17% now to 5%-6% in 2030. The number of people with basic vocational education will also decline, mainly among men. The share of those with tertiary degree will increase – among men to 26% in 2030 and 36% in 2050, while among women to 38% and staggering 52%, respectively. Moreover, by 2030 most of beneficiaries of educational boom will prime-aged (cf. Figure 2). There will be less people on the labour market, but they will be better educated and should be much more productive than the current workforce, cushioning the impact of ageing on the economy.

Figure 2. Projection of the educational structure of the population aged 15-80 years, baseline scenario, 2012 and 2030. Source: IBS (2014).

However, the structure of education matters. In this regard the Polish system has been much less forward-looking. Social and business-related studies still dominate. But in comparison to other European countries, Poland has relatively many more students of education, but much fewer students of health and social services (cf. Figure 3). This doesn’t bode well for population ageing, as there will be a surplus of teachers and a shortage of care-takers and gerontologists, although this may well shift in time if there is a change in demand within the labor market.

Between 2007 and 2011 the share of newly enrolled students in social and economic departments dropped from 40% to 33%, whereas admissions to teacher studies dropped by 2.8%. This was accompanied by an increase in the share of enrolments at technical faculties from 13% to 18%, and in medicine. However, the cohorts entering universities in the last five years (born between 1990 and 1994) were 21% smaller than cohorts riding the initial wave of educational boom (born 1980-1984).

Furthermore, the cohorts entering in 2015-2019 (born 1996-2000) will be 38% smaller than the cohort born 1980-1984. This may suggest that the current skill mismatches could persist for the next decade or two. This will pose big challenges for a system not suited to providing life-long learning.

Figure 3. Structure of tertiary education by groups of faculties in 2011 in Poland, Germany and the EU. Source: IBS (2014).

The lessons from the Polish educational boom show that tertiary education can be expanded relatively quickly, especially when the demand for skilled labour grows, wage premiums are high and the private providers are allowed to cater to the growing demand for education. However, what seems tougher is ensuring that the structure of education faculties and the skills being taught reflect not only the current demands and future needs.

Join the Conversation