With the right kind of reforms, public employment services can do a better job of matching job seekers from poor households. In low and middle-income countries, individuals from poor households find jobs through informal contacts; for example asking friends and family and other members of their limited network. But this type of informal job search tends to channel high concentrations of the poor individuals into informal, low-paid work.

Job seekers especially from poor households need bigger, more formal networks to go beyond the limited opportunities offered by the informal sector in their local communities. This is where public employment services can help, but in developing countries many of these services just simply do not work well: they suffer from limited financing and poor connections to employers, and governments are looking for ways to reform and modernize them to today’s job challenges.

There are lots of cases where developing countries have improved their public employment services and these can serve as models. The lessons from these successful reforms can be distilled and replicated. Based on our recent publication, here are three case-tested strategies that improved the performance, relevance and image of public employment services.

Think about employers first

A key mistake governments often make in reforming public employment services is to encourage lots of job seekers to sign up before getting job vacancies to match them to. Most cases of “Big Bang” success in public employment services modernization had an outreach strategy to get employers to list jobs first. This means targeting employers who have openings or a problem with high employee turnover. To increase listings, this may mean focusing on a growing sector (e.g. tourism in Jamaica); seasonal employers who have tight deadlines to find workers (e.g. construction in Mongolia); or foreign investors that need on-site assistance (e.g. Ireland when it first attracted IT investment).

Going after new employers requires proactive methods. Some useful examples in developing countries include: setting up specialized job fairs (e.g. science and technology in Merida, Mexico), going on-site to small and medium-sized businesses to register new vacancies (e.g. El Salvador), making it easy for employers with little time to register jobs – on-line registries, telephone services, registry at their local business association (as in Honduras, see below).

Not enough job listings to go after?

Another type of employer strategy is to provide a good incentive for training programs that employers can use to get a new employee up to speed. In Mexico, the national training program, Becate, run by the national employment service, places job seekers in 1 to 3 month traineeships in businesses with a firm commitment to hire around 70% of trainees. In 2013 alone, over 300 000 people were trained and 8 out of 10 where hired in sectors such as automotive, food processing, and even aerospace.

Going online is not enough

All the world seems to be moving to online job listings (HH-headhunters in Kazakhstan, Caribbeanjobs.com, Monster.com, etc.), but online job matching relies on an evolved labor market. That kind of labor market may not exist in many developing countries and certainly not for poor individuals who may have difficulties getting access. In the Middle East, hiring is done predominantly by personal relationship that online systems will not make a dent in changing how the labor market works for disadvantaged workers, women, or those with poor technical skills.

Expanding public employment services with a core of walk-in offices in high-traffic areas has proven to be effective in expanding access for both employers and job seekers. In developing countries, face-to-face interaction brings additional advantages in helping change hiring and placement practices. Employers often need assistance to articulate their skills needs, or to upload their job offer into an online system. Job seekers may also need one-on-one help for more effective job searches or learning about training opportunities that they would not know through the online platform.

Don’t go at it alone

Public employment services should draw on the strengths of the private and non-governmental sectors, as available, to get the job done. Public employment services now typically operate within a national market where there are other private or non-profit providers. All the OECD public employment services work in some form of partnerships or at least “joint market” with private and non-profit providers.

For those with explicit partnerships, there are many varieties. For example, many outsource or contract-out specific services to providers who can be paid more directly based on results, as in the United Kingdom. Alternatively, as in Saudi Arabia contracts, walk-in centers are contracted to private providers with the public sector providing oversight and payments to providers based on placement performance.

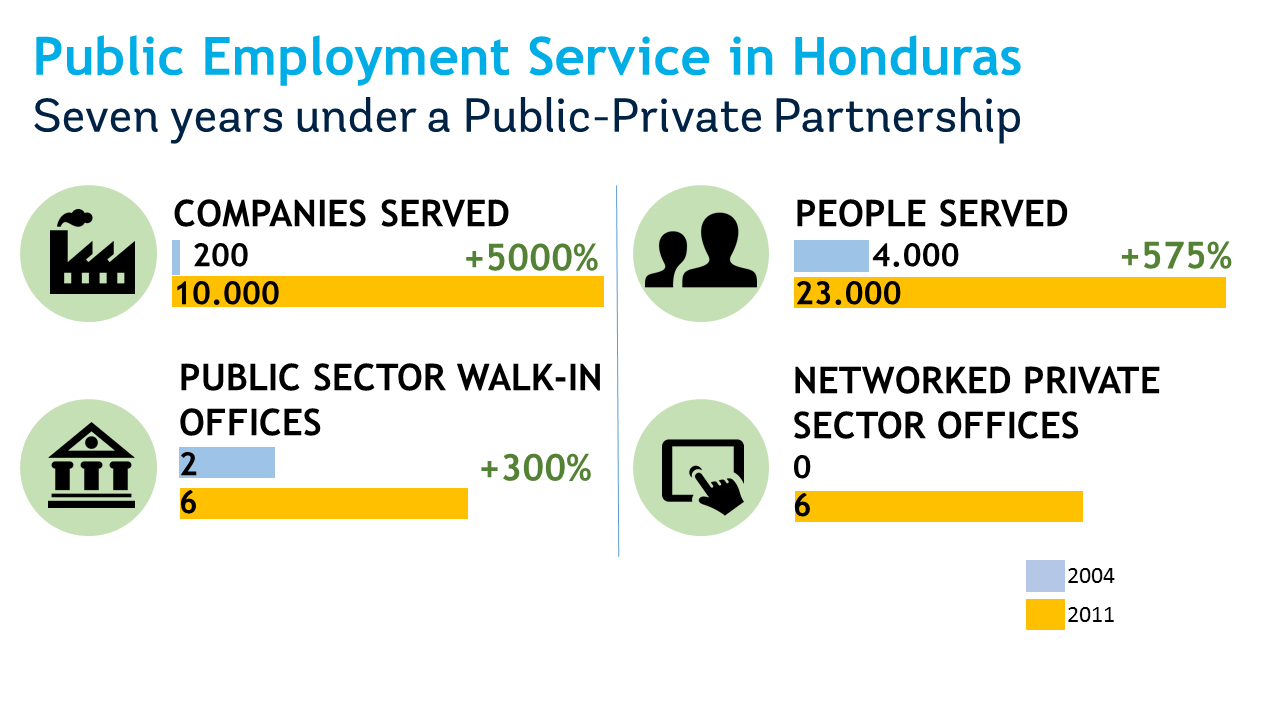

In Honduras, the public employment service signed cooperation agreements with the local Chambers of Commerce to let these associations list jobs for their members on the national data bank and place workers, and the results were impressive.

Seven Years in Honduras Under a Public-Private Partnership

Jamaica is also a good example of this modernization. In 2011, the country had an unemployment rate over 40% — the worst in the continent. When they showed me their remodeled electronic labor exchange (ELE) where job seekers could search for work, there were exactly zero vacancies listed.

Embracing technology was not enough for attracting employers and job seekers. Significant change has come through the combination of an employer outreach strategy, new walk-in services, and partnerships. Six years later, while the Jamaican economy is still feeble, the electronic labor exchange is booming —more than 2000 job placements in sectors from tourism to agribusiness and 9000 employers registered in 2017.

Increasing the number of jobs publicly listed, enabling public and private institutions to better connect workers to jobs will not likely solve the jobs problem in developing countries. But fixing public employment services is a piece of the puzzle that must be improved if we are going to make labor markets work fairer for job seekers especially for the poor and vulnerable.

Follow the World Bank Jobs Group on Twitter @wbg_jobs.

Join the Conversation