Immigrant workers can earn higher wages and accumulate savings to finance self-employment and entrepreneurial activities when they return home. Copyright: Shutterstock

Immigrant workers can earn higher wages and accumulate savings to finance self-employment and entrepreneurial activities when they return home. Copyright: Shutterstock

Temporary worker migration is common. Every year millions of workers in South and Southeast Asia, for instance, depart in search of higher wages in oil-rich Persian Gulf countries on temporary employment contracts. Prior research has largely focused on remittances and how migrant workers increase income and support families at home.

A recent World Bank paper studies migration from a broader perspective: Immigrant workers not only earn higher wages, but they also accumulate savings to finance self-employment and entrepreneurial activities when they return home. We present evidence that temporary migration is an integral part of workers’ savings and investment strategies over a lifetime, with important overall economic benefits for origin countries. We show that key decisions and outcomes are linked: whether, when, and where to emigrate; when to return; how much to save; and what employment and investment options to pursue back home. In particular, we find strong linkages between migration and business creation after migrants return home.

We look at Bangladesh, which ranks fifth worldwide with an estimated 7.8 million workers abroad in 2018. Our analysis uses the World Bank’s Bangladesh Return Migrant Survey 2019, a unique dataset on 5,000 returning migrants. The dataset includes information on migrants' personal and family backgrounds, labor market outcomes, expectations about earning and saving prospects abroad, migration expenditures, sources of income and savings, employment histories at the foreign destination, and labor market activities and earnings after return. We also use the Bangladeshi Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2016-17, which collects information on current international migrants and households without any migrant.

Using this data, we estimate a dynamic model of decisions on emigration, return, and self-employment to evaluate intertwined effects from three key policy changes: decreased migration costs, decreased interest rates for self-employment and entrepreneurship loans, and provision of more accurate information on overseas earnings to would-be migrants.

Our analysis shows that policy makers in low-income countries must consider complex dynamic impacts when designing policy interventions in these areas to avoid unintended effects. Given Bangladesh’s similarities with other migrant sending, lower-income countries, the findings of this paper have relevance for low-skilled temporary migrant workers from many other countries of origin.

Reducing migration costs increases savings and business creation

Migration has a positive effect on self-employment and entrepreneurship. The data shows that the rate of self-employment of return migrants is considerably higher than non-migrants, and for the same migrants prior to migration, especially at younger ages (Figure 1). For instance, 65 percent of 30-year-old return migrants in our sample are self-employed, compared to 28 percent of workers of the same age who have not migrated. But the costs of migration can be high; the average migrant in our sample paid an amount equivalent to about three years of earnings in Bangladesh. Reducing migration costs is the most frequently demanded policy by migrants, advocates, and academics.

Figure 1: Share of self-employment (own account and entrepreneurship) among employed working-age population (males aged 20-55)

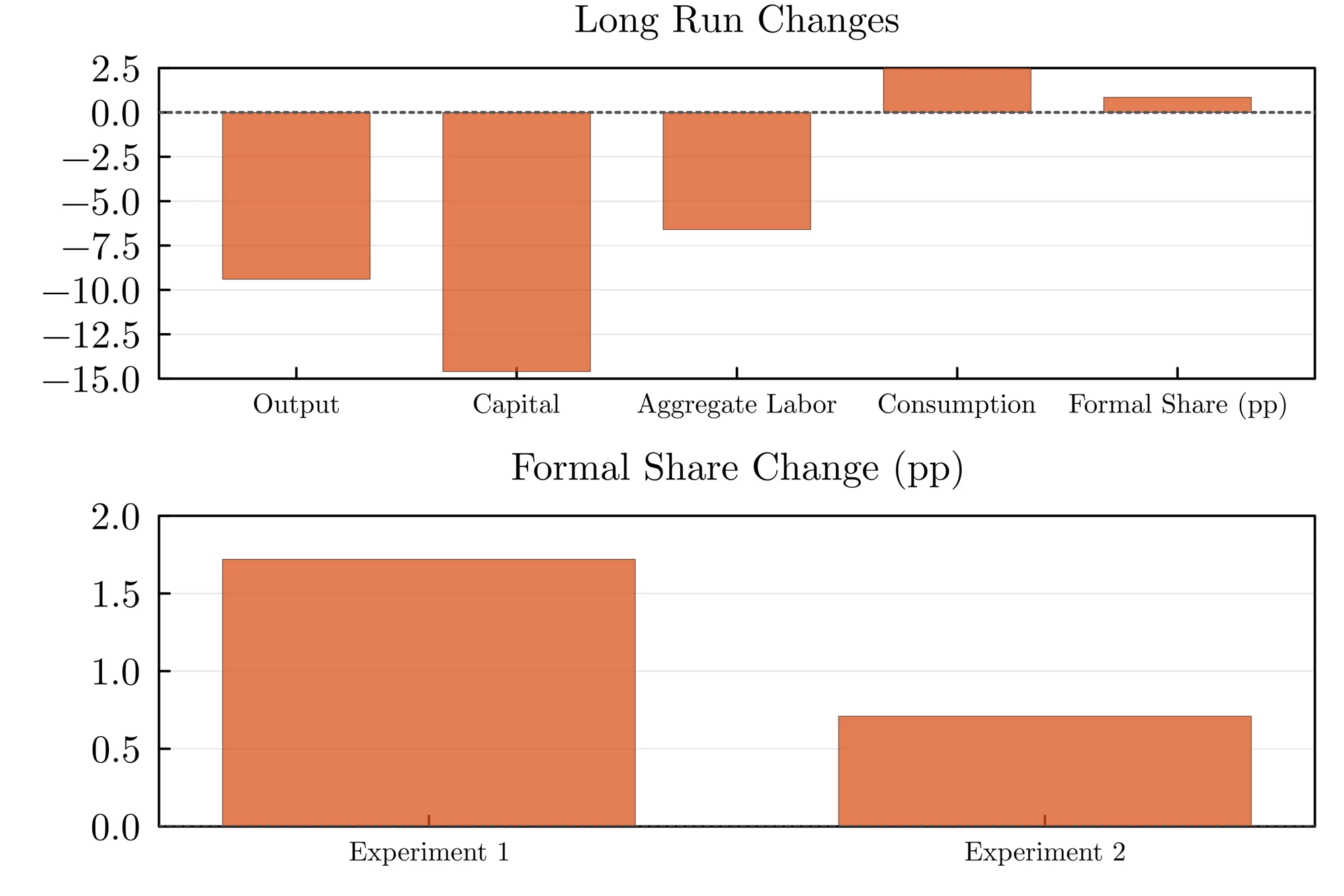

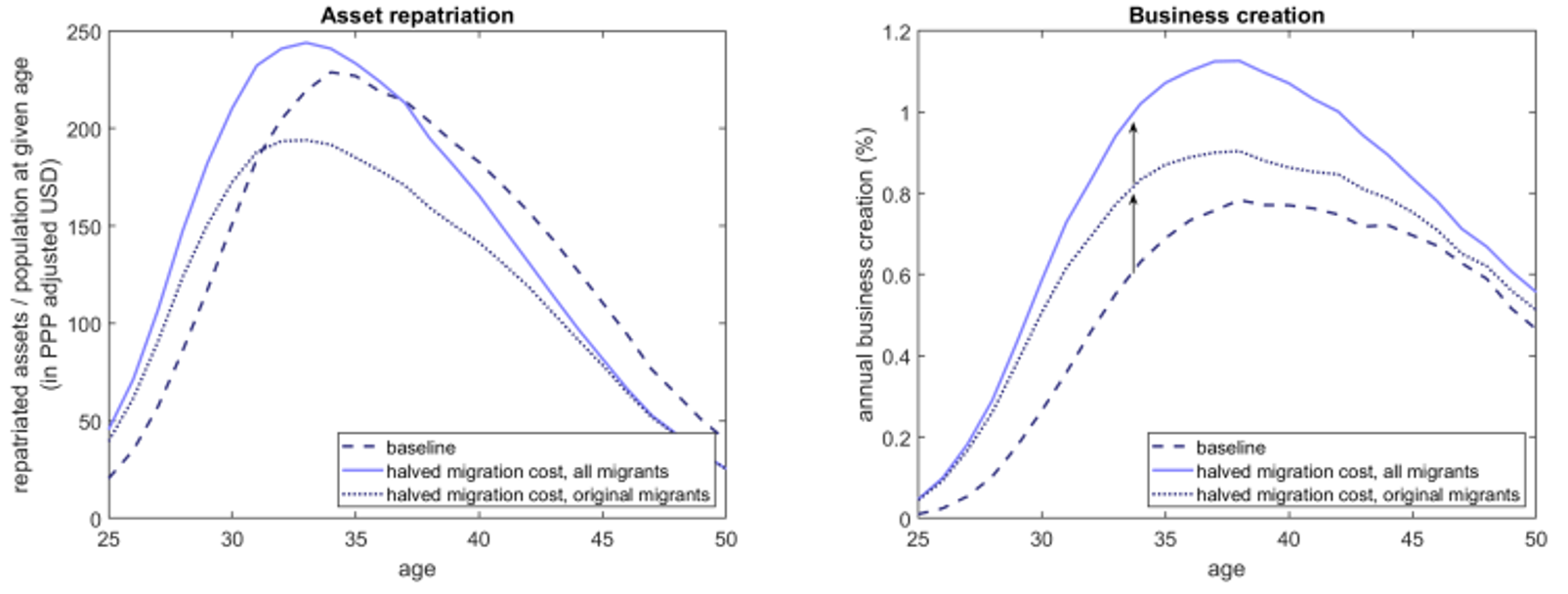

Our model shows that decreasing migration costs—either by limiting the rent-seeking behavior of intermediaries or through migration subsidies—raises the prevalence of emigration. Halving costs increases the migration rate 29 percent over the lifetime of a worker with no secondary education. Lowering costs also shifts migration to younger ages and reduces time spent abroad. Earlier return implies lower savings, but emigration at a younger age and earlier return makes for longer payoff periods and more profitable entrepreneurial investments. We find that combining all effects of lowering migration expenses is expected to significantly increase repatriated savings and business creation: A reduction of migration costs by 50 percent is predicted to increase the annual business creation rate in Bangladesh from 0.7 percent to 1.1 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Simulated effects of a decrease in migration cost

Entrepreneurial loans

Subsidizing and lowering interest rates for entrepreneurial loans may reduce emigration, which would partly undermine the positive effects of the policy on business creation. While this policy makes self-employment and entrepreneurship more attractive and accessible, its effect is undermined by an adjustment in migration behavior. We estimate that halving the entrepreneurial lending rate would lower the emigration rate 5.4 percent and is expected to reduce average migration duration by 6.4 percent. Taken together, these would imply a decrease of 8.4 percent in asset repatriation, thus limiting the positive effect of lower interest rates for business creation in Bangladesh (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Simulated effects of a decrease in the lending rate for self-employment and entrepreneurship

True earnings potential

Informing potential migrants about their true foreign earnings potential may decrease emigration, and therefore decrease benefits derived from returning migrants. Workers who emigrate tend to have biased expectations about wage and savings abroad. Our model evaluates the effect of an information dissemination policy that tells migrants the truth and aligns their expectations about potential earnings abroad with actual mean earnings. Our model predicts that knowing the true expected wage decreases emigration by a sizable 13 percent together with business creation rates (Figure 4). The interests of individuals, therefore, may not align with policymakers’ aims to boost business creation.

Figure 4: Simulated effects of correct expectations about earnings abroad

Join the Conversation