(Photo: Arne Hoel/World Bank)

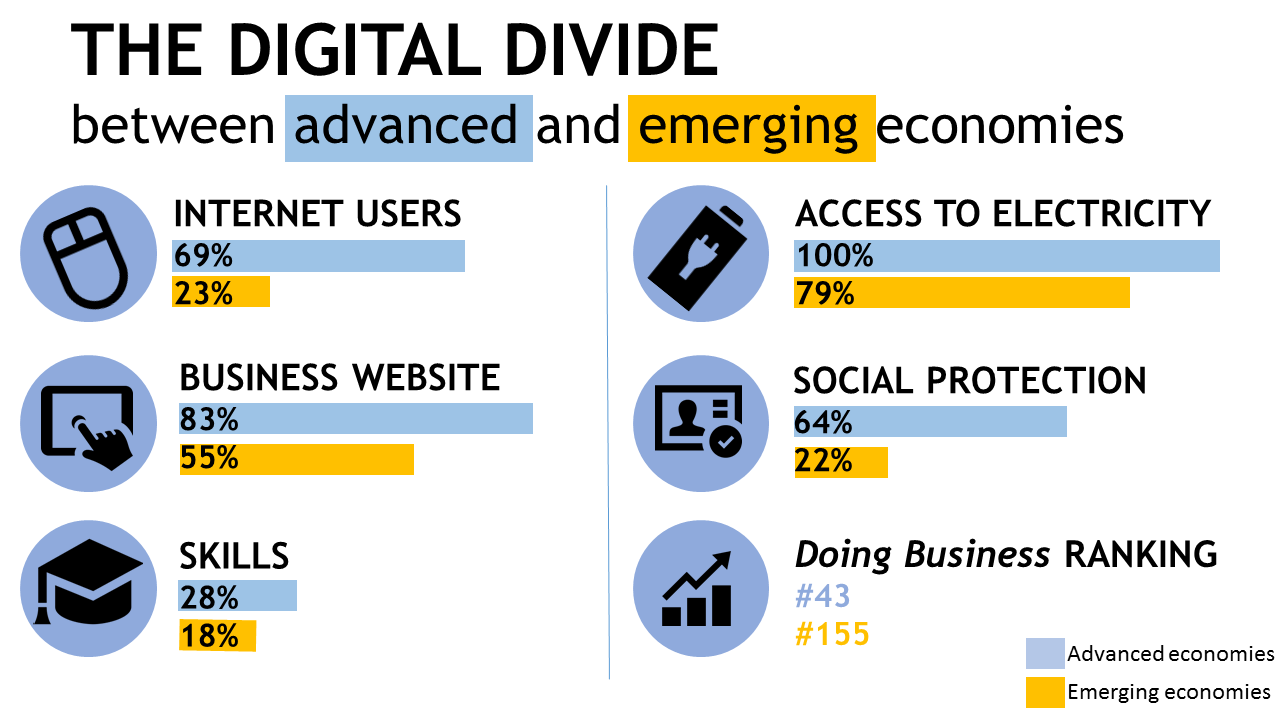

As we explained in previous posts, digital technologies present both threats and opportunities for the employment agenda in developing countries. Yet many countries lack the means to take full advantage of these opportunities, because of limited access to technology, a lack of skills, and the absence of a broad enabling environment, the so-called “analog” complements.

This does not mean that developing countries and groups within countries cannot benefit from technological change. Some have skipped over traditional methods and leapfrogged into adopting new technologies, taking advantage of their "greenfields" to deploy systems such as biometric identification for social programs in India, or drones for medical deliveries rather than by road in Rwanda. About a third of the robots bought by Chinese firms are now manufactured in China, and countries such as India and the Philippines are world leaders in business process outsourcing and IT services. Yet, absent technology access, skills and good analog complements, such advances might be limited to a few businesses or individuals in the larger cities, exacerbating inequality. How could public policies position countries better to mitigate the threats and take maximal advantage of the opportunities?

Leave no one off-line

Technology access in the developing countries often lags the developed world, and within countries, it is typically major cities and towns that are online. Most rural or remote communities, which house four-fifths of the poor, are not online, or they face higher prices or poorer quality services. Divisions also exist across different demographic groups. Women, people with disabilities, social and ethnic minorities, and older people lag behind in access to and use of digital technology. Many individuals and businesses will thus be unable to take advantage of technology to improve productivity and incomes, simply because they do not have access to the “hardware."

Regulatory and market failures often hold back the provision of affordable and reliable Internet access, access to electronic payment systems, and access tow-cost devices. Public interventions may further be necessary to overcome the divides that limit the participation of women, the poor, and rural communities in the digital economy. For example, a number of countries in South Asia and Africa have invested in public-private partnerships to extend Internet connectivity into rural areas.

Building skills for the workforce of the future

But even if the technologies are available, businesses and individuals often lack the necessary skills to use them. Skill gaps exist at two levels. First, many developing countries have limited pools of technically highly skilled workers, limiting innovation, technology transfer, or simply adoption and maintenance. Second, many workers in the developing world do not have the digital literacy — and in some cases, even more basic cognitive and technical skills— to use technology in their occupations. For example, in Africa, about 70 percent of people who do not use the Internet say it is because they do not know how to use it. They miss the opportunity of increasing productivity while increasing the risk that they may be substituted by technology in the future.

Educational systems need significant reforms to impart the technological, but also the non-cognitive skills required to allow the next generations to participate fully in a global digital economy. In cases where wholesale reform is difficult, ‘bridging’ from education to employment could help close some skills gaps. The World Bank has funded such training programs, focusing on connecting young people to jobs by improving access to IT certifications in Mexico or via online work platforms in Kosovo.

Invest in analog complements

Other ‘analog complements’ of digital development that are equally needed to take advantage of the opportunities which digital technologies create — rules and institutions — are often also weaker in developing countries. Access to finance is often a challenge. Electricity and other utilities to run the technologies are often unreliable (or even absent). And administrative barriers and corruption often prevent entrepreneurs to set up businesses in the first place. Improving access to finance, to infrastructures such as electric power, to logistics, and to public services will be critical to unlocking the full range of benefits from digital development.

In middle-income countries, social safety nets would also need to reform to protect "gig" workers and to support those who lose their jobs or need transition assistance. If the future is one of little work, cash transfers and universal basic income schemes —being piloted in the U.S. and Finland— may need to be developed. Yet, technology can also help deliver these complements —through digital financial services, renewable energy, mobile government services, and innovations such as drones to leapfrog weak logistics.

In short, ramping up investment in digital technologies, digital skills and their analog complements, also in low and middle-income countries, is increasingly at the heart of development and poverty reduction. Without this, the attainment of poverty eradication and shared prosperity risks becoming out of reach again.

Follow the World Bank Jobs Group on Twitter @wbg_jobs.

Join the Conversation