In the changing nature of work, diplomas are important, but skills are invaluable.

Being a teacher in Norway may require a very different set of skills than being a teacher in Africa, even though the job title is the same. For example, while teachers in the developed world may need to have digital or foreign language skills, these attributes may not be as essential to become an effective teacher in the rest of the world.

While it sounds intuitive, these specific on-the-job skills are more challenging to measure than, let’s say, years of schooling. Communication skills, problem-solving and social intelligence are all in high demand by employers yet don’t show up on any college transcript.

Fortunately, surveys tailored to measure these types of skills have multiplied over the last decade. They ask workers what type of tasks are required for their jobs, such as reading, being creative or interacting with customers, among many others.

In a recently published working paper, we use these data to estimate how the skill content of jobs vary across countries of different economic strata, and across time. And we used them to predict which skills will lend themselves to the jobs of the future.

We found an interesting pattern.

Chefs, yoga instructors and CEOs are far better positioned in the labor market than, say, accountants. The reason isn't immediately apparent, but it's meaningful.

This is how it works.

The rapid adoption of digital technologies tends to benefit workers with skills that are difficult to replace with a computer, such as creativity, inter-personal skills or leadership. Digital technologies may boost the productivity of workers in these occupations by allowing them to organize and implement their ideas or decisions more rapidly and precisely. These types of jobs are considered intensive in non-routine skills.

In contrast, jobs that are more intensive in routine skills such as accounting or copy editing, and occupations that require repetitive manual operations are more susceptible to being replaced by new technologies. For example, the emergence of industrial robots and software that can process tax returns or proofread documents will render the role of professionals unnecessary in carrying out these tasks.

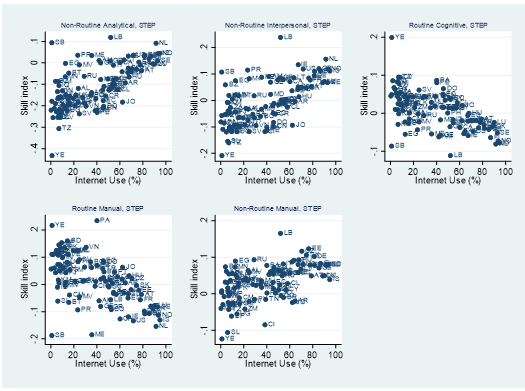

As seen in the figure below, this association between digital technologies and the skill intensity of jobs is strong: Countries with higher rates of internet use are less likely to have jobs intensive in routine skills. After netting out the effect of other factors, we find that an increase of 50 percentage points in internet use – roughly the increase experienced by developing countries since the early 1990s – is associated with a large decline in routine jobs. The drop is equivalent to almost half of the decline experienced by some developing countries since the 1990s.

Figure 1: The Skill Content of Jobs and Digital Technologies

The bottom line is this: while technological progress may improve productivity and wages, it also creates winners and losers. Routine workers fall into the latter group.

Labor market policies could help soften the blow to routine workers as technological change rolls in. Efficient and well-targeted social protection systems, reduced barriers to job mobility and strengthened lifelong learning systems can help protect displaced workers’ incomes and help them find new jobs during a technological shock.

Changing a routine is not easy. But in an age when technology is replacing more and more repetitive tasks, labor market policies like these can help workers to flesh out the skills they bring to the table.

Follow the World Bank Jobs Group on Twitter @wbg_jobs.

Join the Conversation