As I witnessed the official launch of the Saving One Million Lives Program for Results (SOML PforR), a government-led initiative supported by a $500 million World Bank International Development Association credit, I was overcome by several emotions, the foremost of which was hope.

For many, it was simply the launch of a new health program. For me however, it symbolized both the promise of an innovative approach and that of renewed hope. The adoption of a new performance model, a program for results (PforR), heralded a brighter future for Nigeria’s mothers and children.

About 900,000 maternal and child deaths occur annually in Nigeria, largely from preventable causes. These are worrisome statistics, and sadly, a far too common and tragic reality for the average Nigerian woman who has a 1 in 13 chance of dying during childbirth. If she is lucky to make it through delivery with a live baby, her child has an approximately 1 in 9 chance of dying before their fifth birthday.

In a gathering that included executive governors, commissioners of health, permanent secretaries, health managers, and key stakeholders in the health sector, Nigeria’s Minister of Health Professor Isaac F. Adewole was categorical on the need to change these dire statistics. In his words, “it will no longer be business as usual”. For the first time on a national scale, states are going to be rewarded for their improvements in performance on key maternal and child health indicators.

Over the last 20 years, Nigeria’s progress on improving maternal and child health outcomes remains slow, and continues to account for 14% of global maternal mortality. While there has been some improvement in lowering the stunting rate and infant mortality, the country did not meet any of the health-related Millennium Development Goal targets. More can be done and Nigeria has the capacity to do it, as the successful containment of the Ebola virus in August 2014 and the two-year interruption of polio transmission have demonstrated.

Many lessons have been learned from these successes and failures such as the value of strong leadership, political will, team work, community participation, and clear accountability mechanisms. Establishing clearly defined goals, objective measures of success with independent and robust data collection systems that track success are some of the key ingredients. More importantly, Nigeria has learned that inputs (such as drugs, health facilities, and hiring more health workers) alone do not make an effective health system.

The SOML PforR brings together many of these lessons and embodies the collective aspiration for the health of mothers and children, re-orienting the discussion to focus on results for beneficiaries such as increased utilization and coverage of immunization and vitamin A supplementation, rather than inputs.

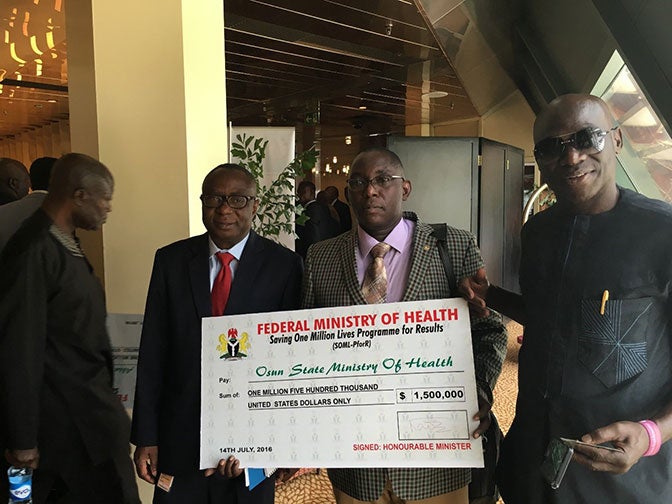

Over the next four years, the World Bank’s support for SOML will use the PforR instrument to encourage greater focus on results, increase accountability, improve measurements, strengthen management, and foster innovation. The PforR will reward states with untied fiscal transfers from the federal government when they achieve improvements in the coverage and quality of key maternal and child health (MCH) services as measured by independent household and health facility surveys.

By focusing on and rewarding results that impact the lives of women and children in the community, the PforR seeks to shift the incentives of health care workers. The hope is that by providing health managers at the state level substantial autonomy over the utilization of these resources for primary health care services, they will be inspired to find homegrown, context-specific solutions to their health care challenges.

The states, and Local Government Areas, are at the frontline of service provision and for the PforR to succeed, they need to implement changes that will visibly impact service delivery at Primary health centers (PHCs) across the country. By doing so, and improving their annual performance on the key indicators of maternal and child health tracked by SOML PforR, they will be able to earn even more funds under the program.

Though it is still early, multiple engagements with state officials at various orientation and technical meetings suggest that despite initial scepticism, there is a swelling of support for this approach and a commitment to the successful implementation of the program.

More broadly, the PforR is a litmus test of performance based models of intergovernmental fiscal transfers; the results of which will have far reaching consequences beyond the health sector.

At the end of the program, we hope to see significantly improved access to skilled birth attendance, immunization, insecticide treated net usage in children, vitamin A supplementation, services to help prevent mother to child transmission of HIV, and better quality health care. Positive results are also expected in the areas of governance and management of primary health care systems.

After decades of business as usual, incentivizing performance through the PforR may well be the catalyst that accelerates access to life saving health interventions and results in a rapid decline in maternal and child mortality. Though the stakes are high, the SOML PforR launch has birthed great hopes that this time around, the odds will be in favour of Nigeria’s mothers and children.

Join the Conversation