In the decade prior to COVID-19, Nigeria made little progress on its sizeable poverty-reduction challenge, despite positive per capita growth. Since then, deep recessions and rising prices have likely made the situation worse. Now, almost half of Nigerians are estimated to be poor: they live below the national poverty line.

Despite waning growth, many Nigerians are working—but working alone is not proving enough to lift them out of poverty because more and better jobs are needed. How are those jobs created, then?

Employment with higher productivity is often generated by a meaningful structural transformation: the process of economic activity and employment shifting from lower-productivity sectors to higher-productivity sectors. So, is Nigeria’s economy transforming? And, if so, does the transformation deliver higher productivity jobs to raise living standards? Or is the structure of employment changing without any meaningful productivity gains?

The trend: from agriculture to services, productivity and next steps

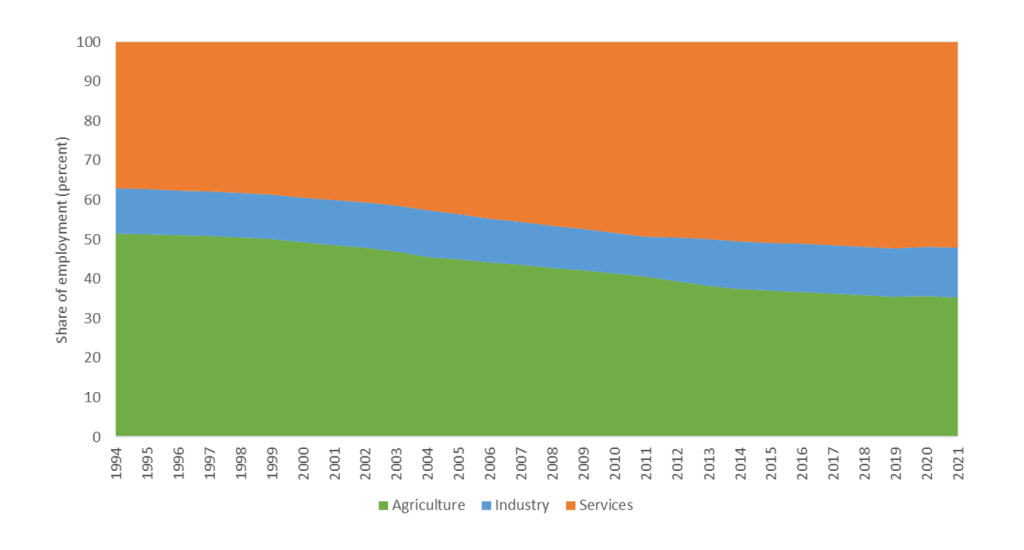

Employment in Nigeria is certainly moving from agriculture to services: 20 years ago, about half of workers were in agriculture and about one third were in services, but now it is the other way around.

Figure 1: Employment sectors in Nigeria, 1994-2021

Also, overall labor productivity is more than 70 percent higher in services than in agriculture. So, all other things equal, employment shifting to services should boost living standards. Why has this not happened?

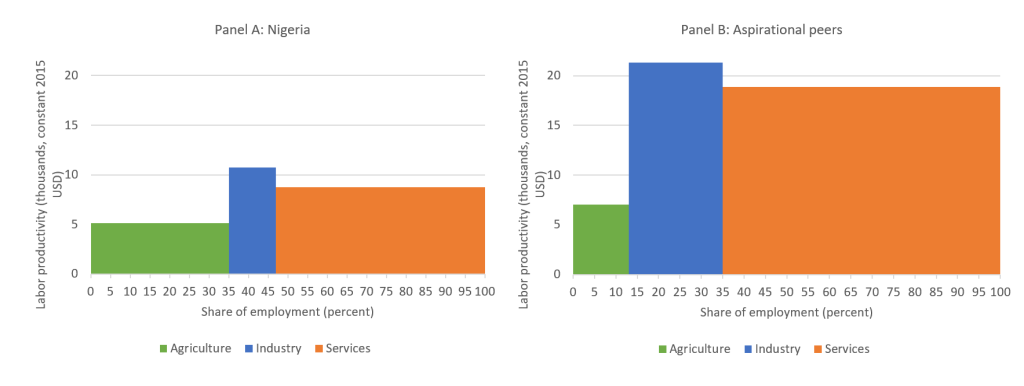

Figure 2: Labor productivity and employment sectors in Nigeria and aspirational peers, 2021

While Nigeria’s productivity is higher in services than in agriculture, peer countries benefit from a much larger productivity premium in services. In Brazil, Mexico, Malaysia, Colombia, Peru, and South Africa combined, labor productivity is around 167 percent higher in services than in agriculture—well over double the premium in Nigeria.

Moreover, the service sector is highly diverse. Within services, jobs in ‘business and finance’ are far more productive than those in ‘commerce and hospitality’—the sub-sector which includes retail and wholesale trade.

Figure 3: Labor productivity by sub-sector in Nigeria, 2017

Retail and wholesale trade jobs offer no guarantee to exit poverty. Unlike jobs in industry and other types of services which are concentrated in richer households, retail and wholesale trade workers are found right across the whole welfare distribution.

Many of the new jobs within the service sector appear to be in retail and wholesale trade, according to data from Nigeria’s new labor force survey. These jobs do not offer the same productivity gains as other service-sector jobs.

In fact, despite growing in the 2000s, labor productivity in services began to decline following the oil price-induced recession in 2016. Thus, it is possible that new workers entered services to cope with income losses, without necessarily finding high-productivity jobs. This was exactly what happened during the COVID-19 crisis.

Thus, it is not surprising that the level of wage jobs has not increased either. Wage jobs are known to be associated with utilizing higher skill levels and allowing workers to exit poverty more than self-employment.

Nigeria therefore needs policies that can enhance a meaningful structural transformation so that the private sector can create more and better jobs.

In the long run, this requires better integrating firms into global value chains and attracting foreign direct investment. This hinges on a stable macro environment, requiring a continuation of fiscal and exchange rate reforms. In addition, openness to international trade by removing trade restrictions and improving trade facilitation, as well as ensuring skills are aligned with the economy’s needs, and upgrading infrastructure are key ingredients of an effective policy mix.

Yet in the short run, finding ways to boost earnings in activities that are currently low productivity and small scale—especially in farm and non-farm household enterprises—will be critical. Such policies could include improving access to inputs and the credit needed to buy them.

Given the immediate potential of Nigeria’s demographic dividend and the country’s growing poverty-reduction challenge, the need to effect evidence-based policies to generate jobs that can lift people out of poverty is more urgent than ever.

Join the Conversation