What goals are good goals? Psychology tells us that good goals are challenging, yet attainable. Easy goals don’t sufficiently challenge us to improve our performance, while unattainable goals tend to demoralize us and result in poor performance. The sweet spot is in the middle: choose a goal that’s tough yet achievable, and performance improves by directing attention, mobilizing effort, and increasing persistence.

Chapter 9 of the 2021 World Development Report: Data for Better Lives sets out an ambitious goal for all countries: build an integrated national data system (INDS). What’s an INDS? It’s a framework that enables the production of data relevant to development, and fosters the equitable and safe flow of data between government, individuals, civil society, academia, and the private sector. It puts people at the center and promotes the use and reuse of data by all participants while safeguarding against misuse.

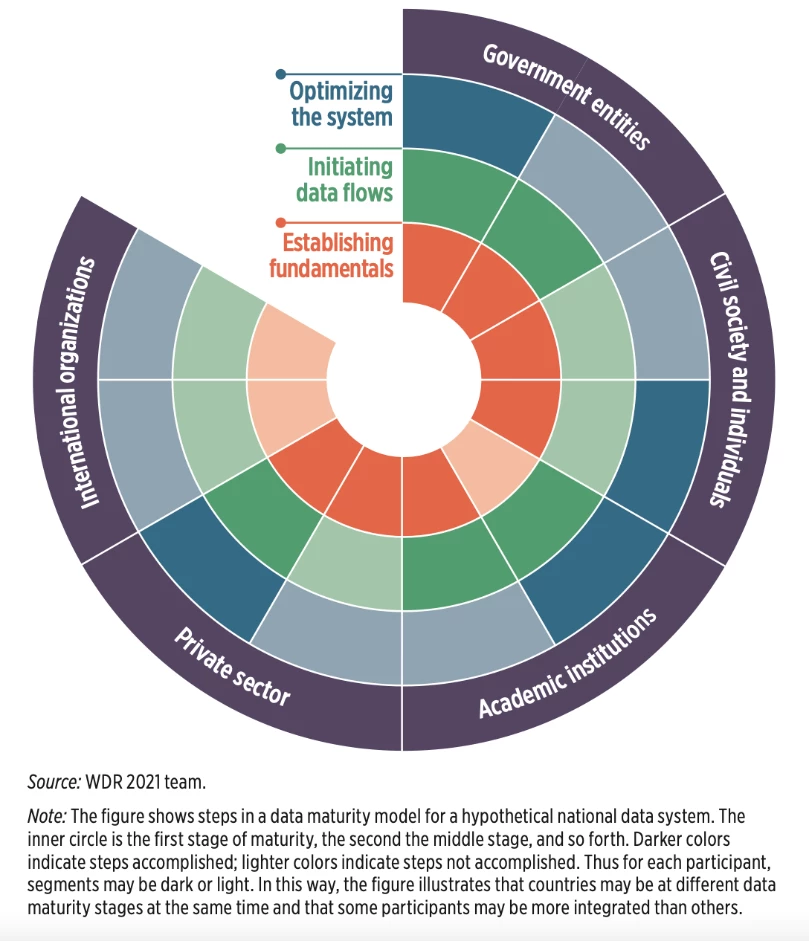

For countries struggling to produce even the most basic statistics, this vision of an integrated national data system may seem unattainable. Yet, over the past years, some countries moved significantly closer to fulfilling this vision. In this blog, we highlight three of them. Their progress shows that across differing contexts, there are specific and attainable goals for realizing this vision and leveraging greater value from data for development. In the 2021 World Development Report: Data for Better Lives, we propose differentiated goals depending on the level of data maturity: At low levels, countries can prioritize establishing the fundamentals of a national data system. Once the fundamentals are in place, countries can seek to initiate data flows. At advanced levels of data maturity, the goal is to optimize the system.

Ghana

Ghana’s statistical system made international headlines in 2010 when adopting revised guidelines for the System of National Accounts (shifting from the 1968 to 1993 guidelines) resulted in a 63% increase of its nominal GDP. Overnight, Ghana moved from a low-income to middle-income status. While the event was taken as an occasion to declare Africa’s statistical tragedy, for Ghana itself, the revision was a reflection of a maturing data system. It was the result of a careful and transparent process that followed global standards and was made possible by new data becoming available.

Since then, Ghana has further invested in the foundations of its data system. In 2016, the National Information Technology Authority (NITA), responsible for implementing Ghana’s ICT policies, opened a tier 3 data center to host all government applications while offering excess capacity to the private sector. Its national strategy for the development of statistics 2018-2022 explicitly recognizes the private sector, nonprofits, and researchers as important data users. And in 2019, it passed the Statistical Service Act 2019, providing the Ghana Statistical Services (GSS) with a leading role in the national statistical system and a mandate to set standards for data generation across ministries, departments, and agencies.

Building on these foundations, Ghana is initiating data flows between the different participants of the national data system. For example, NITA’s Ghana Open Data Initiative created a central repository, hosting more than 300 datasets in open data format from various government agencies. GSS developed a data portal presenting and disseminating Ghana’s data on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) both for national and international audiences. A collaboration between GSS and the parliament seeks to institutionalize data use in policymaking—for example, by training officers in the parliament on available data sources. And when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, GSS partnered with the private sector for analyzing the effect of mobility restrictions using anonymized mobile phone data. Ghana’s national data system can also build on a strong and inclusive civil society. For example, the I Am Aware initiative by the NGO Ghana Centre for Democratic Development disseminates administrative data on various sectors through district-level rankings, bulletins, and a free SMS platform.

Ghana’s case illustrates that with limited resources and lower levels of data maturity, a government can adopt an intentional, whole-of-government, and multistakeholder approach to data governance. Ghana’s progress is also evidenced by the Statistical Performance Indicators—with a score of 62, it is among the top performers in Africa.

Mexico

At the center of Mexico’s data system is the National Statistical and Geographical Institute (INEGI), a national statistics office built on strong fundamentals. Economic and financial crises in 1983 and 1994 created the need for credible statistics following international standards while technocratic governments strengthened internal data demand. INEGI’s institutional foundation was further improved in 2008 when it became an autonomous body, shielding it from political interference. A good relationship with the Ministry of Finance ensured a steady and stable flow of funding.

INEGI is part of a wider data system that promotes data flows both within the government and other actors. States and local municipalities collect and share 600 datasets with the public via the central government’s open data network, Red México Abierto, following centralized data quality standards. InteroperaMX facilitates the exchange of data between government departments and therefore the efficient delivery of services. For example, birth certificates, issued at the state level and required as proof of identity for at least 45% of all services at the federal level, can be accessed online through the interoperability of the national population registry and state-level databases. And Mexico is one of the first countries to grant data portability rights to individuals, enabling them to obtain and transfer personal data as they switch between services or product providers.

Mexico’s data system also integrates academia, civil society, and the media. INEGI offers researchers access to confidential data through its Microdata Laboratory, a data enclave on its premises, while also actively engaging the civil society and media through regular briefings and rewarding outstanding use of their data with prizes. In addition to promoting innovative data use by non-governmental actors, the government of Mexico also actively learns from data innovations from academia and civil society. For example, randomized impact evaluations, originally pioneered by academics, are now part of the government’s policymaking practice through the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL), which implements and commissions evaluations of the government’s social policies.

Estonia

Estonia is at the forefront of digital government. i-Voting, e-business, e-health, e-school—there is hardly any area of life where Estonians cannot access public services online. On the backend, these services are enabled by the trustworthy production, exchange, and use of data.

Estonia was not predestined to become a leader in this space. When regaining independence in 1991 as an upper-middle-income country and discarding its legacy systems, it started building its national data system from scratch. The new country quickly established the necessary fundamentals: It pushed programs to increase internet penetration and in the 1990s, it was one of the first countries in the world to formulate an e-government strategy. It also defined clear institutional mandates: a Central Information Officer (CIO) operating at the political-strategic level in the Cabinet Office and the Estonian Information Service Authority, charged with the central management and development of basic digital infrastructure.

With the fundamentals in place, Estonia initiated data flows with two key technologies: (i) eID, a system of digital and mobile identification, and (ii) X-Road, an open-source data exchange layer that allows linked databases to automatically exchange information. These technologies were flanked by both enablers and safeguards. Adopting the once-only principle meant that citizens’ data could only be collected and stored once by the government, therefore requiring departments and agencies to share data with each other. But also data protection was built-in by design. For example, only citizens can authorize the aggregation of their data, and on the State Portal, citizens can always keep an eye on who is sharing their data and for what purposes. According to Estonia’s President Kersti Kaljulaid, this transparency and data protection were key in building trust in the system.

The variety of steps taken by these countries illustrate that no size fits all—in the end, each country needs to carve out its own path towards an integrated national data system. Nevertheless, their experiences also show that an integrated national data system is not just an aspirational model. It is something that every country can work toward today. With a functional INDS in place, users can safely access public and private data sources, learn from one another’s analysis, and gain insight that can help to improve lives.

To download the full report, click here.

Read more about Chapter 9 of the report here.

To learn more about the World Development Report 2021, please visit this website.

Join the Conversation