Remote sensing techniques in the Amazon can provide a wide range of data, from deforested areas to potential oil and gas exploration sites. How can the sustainable development need of indigenous peoples be addressed without exploiting these vulnerable populations?

Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7) aims to ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy services for all. However, isolated indigenous communities in the Amazon region are often left behind when national electrification plans are developed, which is usually attributed to the high costs of expanding electricity grids to remote areas. Due to these circumstances, indigenous peoples are more vulnerable to, among others, diseases, extreme climate events and food shortages.

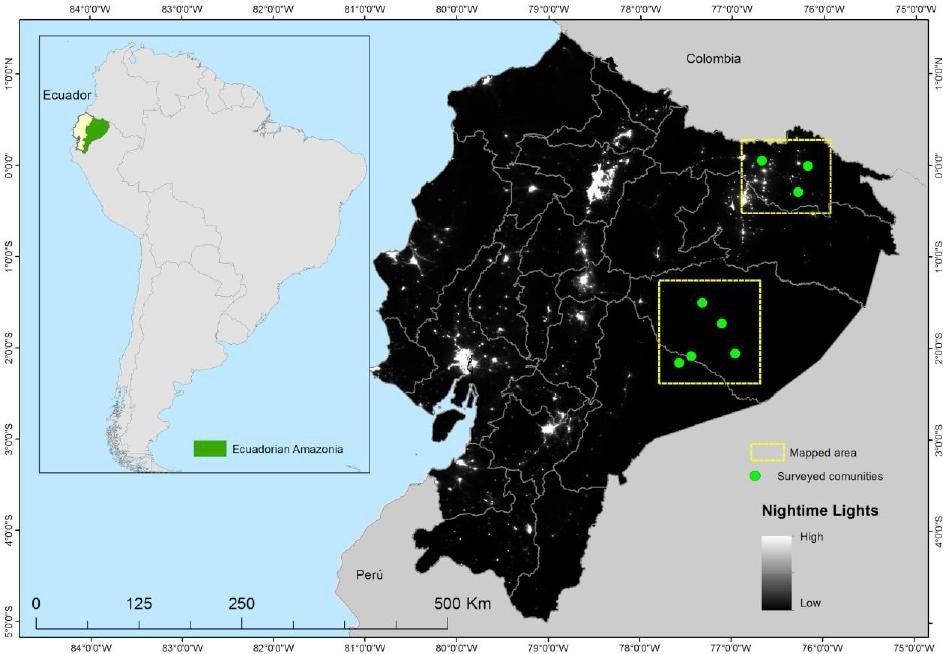

The Data Innovation Fund (DIF) of the Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building III (TFSCB-III) supported a project led by the University of Bonn Center for Remote Sensing of Land Surfaces (ZFL) to tackle this problem. The project “Participatory Mapping to Support Sustainable Energy for All in the Amazon (SE4Amazonian)” improved the data for those who are usually left out of the electricity supply in the Ecuadorian Amazon by using remote sensing and GIS to develop rural electrification plans for some of the remote areas. This project also conducted capacity building activities for the indigenous community. It involved indigenous local technicians to carry out household surveys in remote indigenous communities and used an innovative cellphone app (GeoFarmer) that enabled participatory data collection focused on the communities’ development and energy needs. This collaboration ensured indigenous communities’ participation and that their ideas and needs were incorporated in the electrification planning.

“[...] Solar system that are going to be designed and installed in the Amazon should

be strong enough, because they usually break in our harsh environment. Usually they

design system to provide energy for only 3 lights, we need more energy to develop. So

take into account this for designing solar systems [...]”

Jonathan Piaguaje (participant from indigenous territory, Sekoya)

“[...] One community already has energy grid but they don´t want to use it as this

grid is also used for the mining companies – they want to have their own energy and

sustainable energy as they don´t want to be used as an “instrument” for the

government/mining companies [...]”

Mario Ruiz (participant from indigenous territory, Sapara)

Figure 2 shows a hand drawn map by an indigenous technician side by side with the corresponding satellite imagery. The map provides valuable information about the types of buildings and services, such as churches and communal houses. Although the scale and distances are not accurate, this demonstrates the capacity of the local technicians to provide a great level of detail.

The imagery data combined with participatory mapping data from the household surveys made indigenous people visible on a map where they were “invisible” before. The data were used for the analysis of renewable energy power options for the remote indigenous communities and sped up decision making with rapid, cost-effective, and spatially explicit information on the energy needs of indigenous people in the Amazonia. While the use of the data on the indigenous people added tremendous value in the project implementation process, the team was well aware of the data sensitivity issues that could pose a risk such as the exploitation of natural resources for hydropower constructions, mining and oil extraction, logging activities, and the like. During the project implementation, different strategies were adopted to ensure data protection and anonymity in all publications. GeoFarmer used a private server of AmazonGISnet to protect stored data. Data were presented among project team, local partners, and indigenous communities, yet only used to develop the geospatial energy model.

What’s next

The project, carried out in Ecuador, was a catalyst for further approaches in the Amazon region and elsewhere. The project framework could scale up in the whole Amazon region. The trained local indigenous technicians will be able to replicate the approach in other communities such as Colombia and Bolivia in the Amazon basin. In fact, an initial exploration of this application in Bolivia and Colombia has started.

As mentioned above, the project targeted SDG 7, and the project outcomes indicated that the access to clean electricity increases the ability to achieve other SDGs in the indigenous communities too. For instance, access to electricity (using a refrigerator) can lead to better healthcare services (storing vaccines), and electricity (providing light) can help improve education (studying at night).

When the framework and application of the project are scaled up in the broader Amazon region, a strict regulation on personal data protection should be enacted and monitored by neutral and independent organizations where indigenous leaders and communities are the main supervisors.

The Trust Fund for Statistical Capacity Building III (TFSCB-III) is supported by the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Ireland, and the Governments of Canada and Korea.

For more information about TFSCB, please visit our website.

For more information about this project, please click here.

Join the Conversation