When analyzing poverty, only looking at unemployment rates will be insufficient and misleading. Instead, job quality – underemployment, people’s specific activities and occupations, and markers of formality – is fundamental for understanding the labor market and providing recommendations for policies.

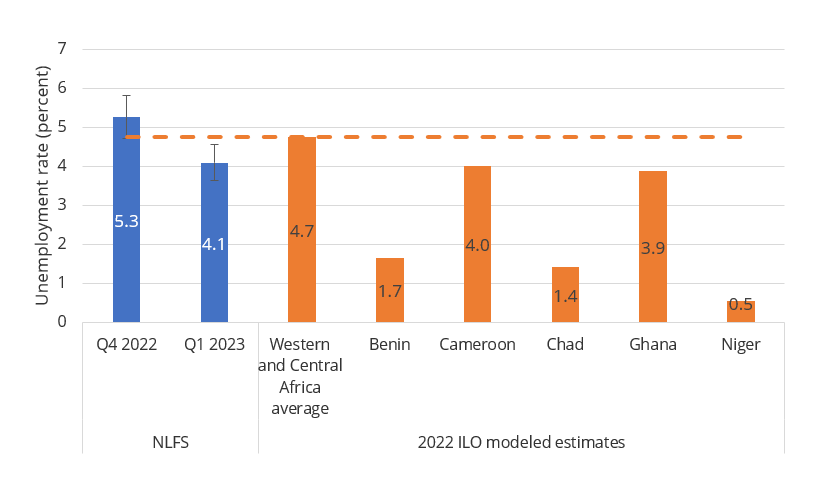

In the case of a country like Nigeria, unemployment has proved a difficult statistic to interpret. Nigeria’s unemployment rate stood at 33.3 percent in Q4 of 2020. However, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) recently reported unemployment rates of 5.3 percent (Q4 2022) and 4.1 percent (Q1 2023), based on the new Nigeria Labour Force Survey (NLFS).

How can this make sense?

To begin, the definition of unemployment has changed to bring it more in line with the standards of the International Labour Organization (ILO). For the new NLFS, the “employed” covers anyone who worked one hour or more for pay or profit in the last seven days, even if they were temporarily absent. The “unemployed” are those individuals who are not employed but are (1) actively searching for paid work and (2) available to start paid work, either last week or within the next two weeks.

In Nigeria’s previous Unemployment Reports, the headline unemployment rate – like the 33.3 percent in Q4 2020 – included not only those who were not employed (and were searching and available) but also those working 1-19 hours per week. Thus, this headline number mixed unemployment and some proxy of time-based underemployment – although alongside this, NBS always reported unemployment according to the “international” definition as well. Additionally, temporary absences were not explicitly considered before, so the new approach correctly expands the count of employed people.

Another change in the definition moves subsistence agricultural workers from being counted as “employed” to being out of the labor force, as they produce goods for households rather than for the market. This way, they are treated in the same way as household members providing services for their household, like childcare, water fetching, cooking and so on. On top of these definitional and questionnaire changes, the new NLFS has made crucial improvements to sampling, fieldwork management, and data quality monitoring – this includes limiting the bias brought about by “proxy response”, whereby one household member responds to the questionnaire on behalf of another.

Equipped with these improvements, the new unemployment rate can be interpreted more clearly, as it avoids lumping together different concepts including unemployment, time-based under-employment, and a notion of sufficient livelihoods. It also allows international comparison. For example, Nigeria’s unemployment rate is of the same magnitude as in all of Western and Central Africa, where it stood at 4.7 percent in 2022.

Unemployment in Nigeria and in Western and Central Africa

Note: NLFS standard errors clustered by enumeration area and adjusted for state-level stratification of the sample. Source: NLFS, World Development Indicators, and NBS calculations.

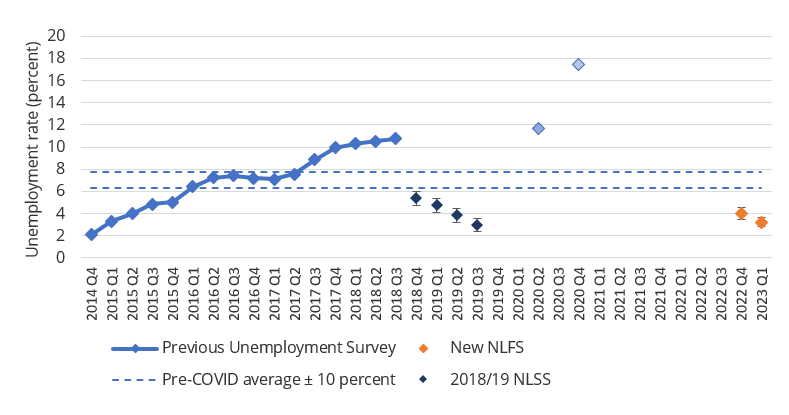

The unemployment rate is also consistent with the situation pre-COVID. We built a bridge to previous data by harmonizing the working age, the treatment of temporary absences, and the treatment of subsistence agriculture, as well as applying the ILO definition of unemployment.

Before 2018, unemployment rates (using the “international” methodology) were always single digit, in line with the current estimates. It was only during the COVID-19 period that unemployment spiked in Nigeria.

Unemployment rate estimates for Nigeria, 2014-2023

Note: New international definition of unemployment classes those who are not working/employed even for one hour but who are searching and available as unemployed. Estimates from COVID-19 period shown in lighter shade. Source: NBS Unemployment Reports, 2018/19 NLSS, NLFS, and World Bank estimates.

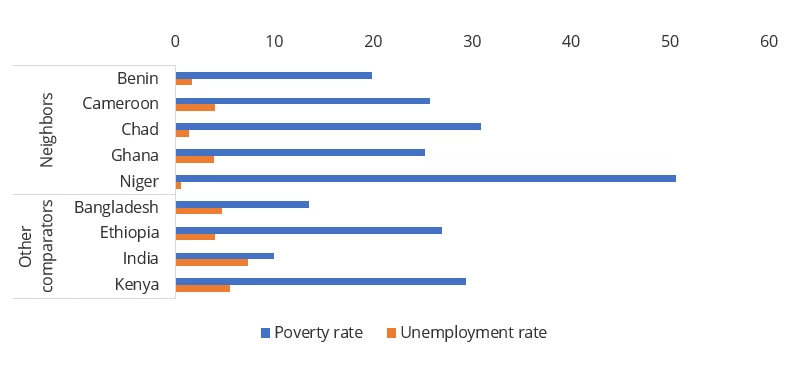

But how meaningful is a single-digit unemployment rate in a country where around a third of the population lives in poverty? The unemployment rate is certainly helpful in understanding seasonal fluctuations and short-term shocks. Yet there is no guarantee that it is correlated with poverty – the most direct measure of whether people have sufficient livelihoods.

In fact, many poor countries have very low unemployment. And within Nigeria, poor and non-poor Nigerians were about equally likely to work in 2018/19. Unemployment was, if anything, higher among richer households.

Poverty and unemployment in Nigeria’s neighbors and other comparator countries

Note: Poverty rate calculated using the latest available data and the 2.15 USD 2017 PPP per person per day international poverty line. Unemployment rates shown are the ILO modeled estimates. Source: Poverty and Inequality Platform, ILOSTAT, and World Bank estimates.

How can poverty and unemployment move in different directions? When prices increase but wages remain low, households – and especially the poorest among them – have to find any means to increase household income. They will find some work to do, for example, through small-scale agriculture, petty trading, or basic services – even if this work has very low productivity.

At the same time, richer households can afford to remain unemployed for longer while searching for a better job. Most Nigerians cannot afford to spend long spells out of employment searching for jobs, especially given the sparse coverage of social protection. Without such support, “if you do not work, you cannot eat”, and unemployment can stay low, even when poverty is widespread.

Therefore, to understand the structural health of an economy and its labor market, we need to be more nuanced with the help of additional indicators. Poverty and wellbeing are determined much more by what you do rather than whether you are employed. For example, wage jobs – being employed and paid by someone else – are better at keeping workers out of poverty. Such jobs, however, are rare in Nigeria: just 11.8 percent of employed Nigerians were primarily engaged in wage jobs in Q1 2023.

Some employed Nigerians are “underemployed”, meaning that they work less than 40 hours per week but declare themselves willing and available to work more. About 12.2 percent of employed Nigerians were underemployed in Q1 2023. Some Nigerians even search on the job, reflecting dissatisfaction with their current job or earnings. Around 7.2 percent of working-age Nigerians were employed, but searching for additional work in Q1 2023.

The NLFS collects a host of indicators on job quality that will provide vital insights into monitoring progress towards generating the types of jobs Nigeria needs to reduce poverty. By fully harnessing its rich, high-quality data – and not just looking at unemployment – the NLFS has the potential to provide vital policy guidance for many years to come.

Join the Conversation